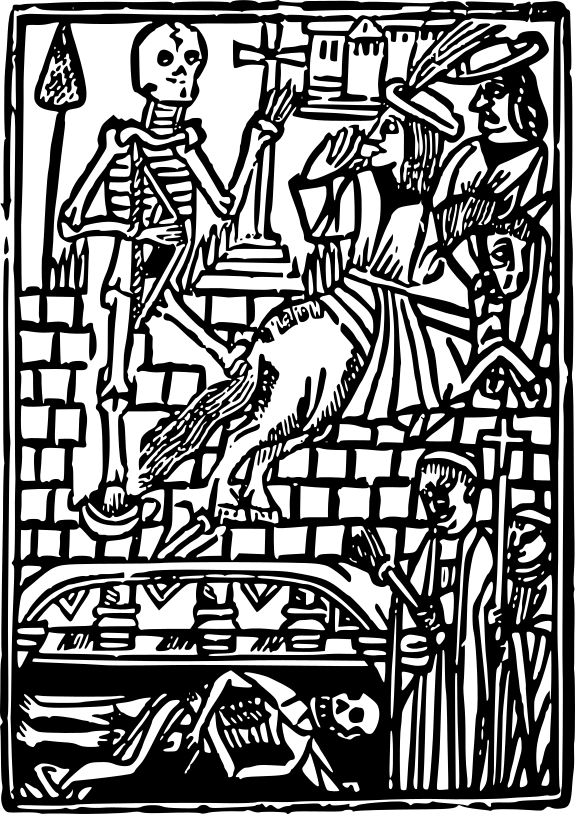

This is a very small cut from a Catalan chronicle printed in 1547, and here Dr. Boli must confess that he is not as much of a Catalan reader as he ought to be. It is a frustrating experience, because the language is close enough to French that it seems as though one ought to be able to read it; but aside from the language barrier, the book is printed virtually without punctuation, and words divide at the ends of lines without any such warning as a hyphen or a “dangerous curve” sign, and proper names are printed without capitals, and abbreviations are frequently employed—all of which makes the text just a little difficult. But it seems like something one would want to know about. Clearly if things like this were happening in Spain, then Spain was a very exciting place.

So we turn to Google and search by image, uploading this picture to see what Google can find. And here is what Google tells us:

Possible related search: dot

When used as a diacritic mark, the term dot is usually reserved for the interpunct, or to the glyphs ‘combining dot above’ and ‘combining dot below’ which may be combined with some letters of the extended Latin alphabets in use in Central European languages and Vietnamese. Wikipedia

So naturally the first site in the results is the Department of Transportation.

Now, having looked a little further at the text, Dr. Boli believes he may have recognized the story. He will provisionally identify it as the tale of King Wamba (spelled bamba in the Catalan chronicle, which is easily explained by the Iberian inability to distinguish the V and B sounds) and St. Giles, in which Wamba, out hunting, had accidentally shot and wounded Giles, and then cared for the wounded saint and ultimately built a monastery for the pilgrims who came to the spot. On this identification, the figure with the bow is meant to be Wamba—but why so skeletal? Dr. Boli had tried to stretch the point and suggest that this was the engraver’s attempt to represent the king in armor, but he was assured by an expert in medieval and Renaissance armor that there was no possibility that any engraver, no matter how lacking in skill, would make armor look like that. Otherwise the interpretation is plausible, since the other characters in surrounding text are known figures in the history and legend of Wamba. Clearly, however, the woodcut brings many incidents from different times together, and Dr. Boli does not pretend to understand all the symbolism.