Ginger Brooks Takahashi: What Causes One to Break Their Silence, 2020.

As a work of visual art, it could be criticized. Perhaps the most telling criticism of it is that Dr. Boli feels perfectly confident in publishing this photograph of it here, because any court in the land would hold that the visual aspect of the work does not rise to the level of originality required to establish a copyright in the United States of America. Copyright law is a mess in many ways, but it has its uses in the field of art criticism.

But it is not merely a work of visual art. It also speaks. The wall plaque says that the sound lasts for eight minutes and thirty-six seconds, but that is a lie. The sound lasts forever. It loops back to the beginning and starts over. The thing never stops speaking. It is not egregiously loud; it speaks at a normal conversational volume. But it never shuts up.

What does it say? Well, it talks about smells a lot. “Sulfur… rotten eggs… rotten eggs… rotten eggs… sulfur… rotten eggs… rotten eggs… like burning plastic… sulfur…”

Perhaps if it did nothing else, it would qualify as surrealist poetry. But art that is open to interpretation is not known in the world of art today. The interpretation must be controlled by the artist, because the artist has an important opinion that you must not misunderstand. Therefore, the speaking bullhorn also gives us enough context to understand that it is talking about the characteristic smells of heavy industry. Then it begins a long informative lecture about tariffs on foreign steel and aluminum.

The entire gallery is filled with this chatter, and it leaks into the next gallery. The voice is not interesting: we assume it is the voice of the artist herself, and she has no rhetorical skill. She drones. Because it is sound, it cannot be escaped the way one would escape an ugly picture by turning one’s back on it. The only way to escape is to leave the gallery and go to a gallery far enough away that it cannot be heard. If you wanted to enjoy some of the other art in that gallery, which holds objects from a wide range of eras, then, the artist might tell you, tough.

Now let us examine another work in the same museum.

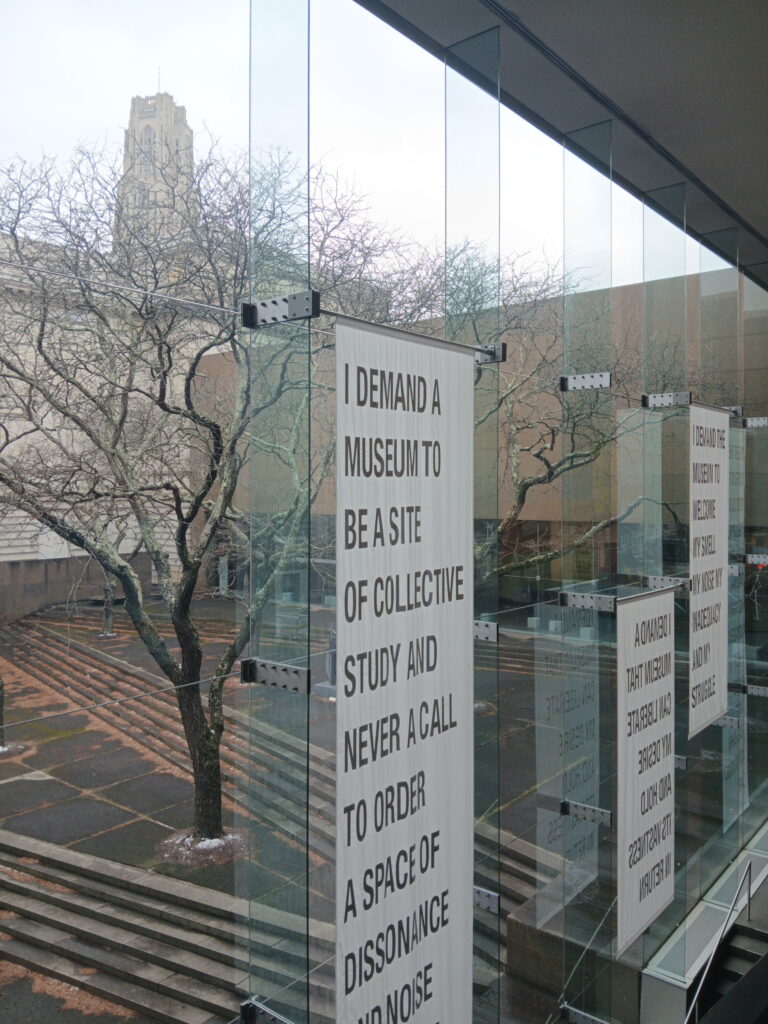

Andrea Geyer: Manifest.

These words, as words, probably do rise to the level of originality required to create a copyright, in the same way that a corporate memo does. However, the doctrine of “fair use” permits us to reproduce a section of the work for the purpose of criticism. The actual work is much more extensive, because there are several more of these plain white fabric banners with plain black gothic capitals on them. (The banners are the art; the glass around them is just the building, which was there before the art and will probably still be there when the next generation of curators repudiates this art as a public embarrassment.) Perhaps you think we deliberately chose the dullest and most unpoetic of the banners to make a point. We invite you to visit the museum and draw your own conclusions. The banners are all similar lists of “demands,” and they all have roughly the same message: my view of what a museum should be is the correct one, and you are a bad person if you disagree. The demands are not expressed in poetic or colorful language, and the banners have nothing interesting about them visually, so the art lies only in the opinion of the artist. There is nothing else to it.

Together, these two works form a complete encyclopedia of what “art” has become in the early twenty-first century: unadorned declarative text and a bullhorn. The message had become the most important thing by the end of the twentieth century, but now, in the twenty-first, the message is the only thing. Everything else that might distract from it, such as beauty or complexity or ambiguity, is eliminated.

If you complain that these things are not art, or are bad art, then the people in charge of Art will call you names and dismiss your opinion as worthless, because the opinion of someone who sticks black letters on white fabric is worth much more than yours is. But Dr. Boli has been around long enough to develop an immunity to insults, so he is willing to say what others will not say. This stuff is bad art. It is not beautiful; it is not skillful; it is not interesting; it is not even informative; but it is annoying.

It seems that all the rules about what is art and what is not art have been repealed. And before we complain and demand that the rules be reinstated, let us point out the positive side of the current state of things. Because there are no rules, we have yammering bullhorns, and we also have Bouguereau. Since Dr. Boli knows that some of his readers are particular lovers of Bouguereau, he will end his complaint with one of Bouguereau’s trademark impossibly scrubbed and callus-free farmgirls. You can see it at the Carnegie Museum of Art, just out of reach of the blabbering bullhorn: Faneuse or The Hay-Maker.

Meanwhile, let us give today’s artists the credit due them. Ginger Brooks Takahashi created a work called What Causes One to Break Their Silence, and it caused Dr. Boli to break his silence. Mission accomplished.