Posts filed under “Travel”

MEMOIRS, ETC.

This single chapter of an otherwise unknown memoir, written in a pocket memorandum book with the title “Memoirs, etc.,” on the cover, was found in a steamer trunk purchased at a St. Vincent de Paul store in Monessen, Penna. It is not known whether any other chapters are extant, or indeed whether any others were ever written.

When I came home from my last trip to the Arctic, I decided that the time for exploring had passed, and I would devote myself to recording my many adventures. Instead, I found myself on a ship bound for the Antarctic. I had mistaken it for the No. 71 streetcar, you see. But once I was aboard there was no turning back, so the Antarctic adventures must be added to the catalogue, where they neatly balance the Arctic ones, although the latter include fewer penguins. Then there are the tropical adventures, the sea stories, and my time spent on a still-nameless desert island with no one but my valet and the Edgewood Symphony Orchestra for company. I have lived a full life, and though it may seem at first glance that my adventures are disconnected and episodic, yet you will find, if you have the patience, a principle of unity among them, a stream that runs through them all and makes the disparate episodes one single story.

My story, like every story, begins with the creation of the world. For the sake of brevity, however, let us begin a little later than that. I might begin with the prodigies that accompanied my birth, but any reasonably complete astronomical almanac should supply the relevant details. I might begin with my education, but it was not different in any remarkable way from that of any other young person with an unusual destiny: the classics, the better class of modern European languages, a smattering of the Polynesian dialects, and enough of anatomy not to embarrass myself too badly in a surgical theater should the occasion arise. I shall therefore leave those early periods of my life to the reader’s imagination or research, and instead begin with my discovery of the island that bears my name.

We had set sail from the port of Sailport, intending to reach the Fortunate Isles by late September. I was a young man, green in years, and was therefore brought in as the ship’s botanist; but you can imagine my disappointment when I found that, apart from a few strands of kelp dried on the anchor, there was not a green plant to be found on board the entire ship. I spent most of my time, therefore, either memorizing Gruenteufel’s Flora of the Undiscovered Tropical Isles (5th ed.) or observing the clouds, since the species, behavior, and complex mating rituals of clouds have always fascinated me.

On our sixth day out of port, we were hailed by a barque returning from the Fortunate Isles, whose crew being entirely Slovakian (though she was sailing under a Ruthenian flag), I was called upon to act as interpreter. They informed us that the Fortunate Isles were under quarantine for an outbreak of agoraphobia in a highly contagious strain; that the main harbor at Blessed Shore, the capital, had been filled in by the outflow of a pesky volcano; that the secondary harbor at Allswell was infested with ship-eating squid; and that the governor had lost the islands to the Spanish in a poker game.

Under these circumstances, it was clearly futile to continue on our present course. Thinking I might spare the captain some trouble, therefore, I gave the helmsman the order to come about hard to starboard, whereupon we immediately ran aground on an island I had not noticed on our right hand.

It had perhaps been an error to give the order without first checking for islands in the immediate vicinity. However, as our captain remarked, what’s done is done, and our unexpected grounding would give us a chance to catch up on some of the miscellaneous repairs to the ship that needed doing, such as the gaping hole near the prow caused by our unexpected grounding. The captain delegated a certain number of men who were familiar with the arcana of duct tape to perform the repairs, while I was to lead a party to the interior of the island, which did not appear on any of our charts, to see whether anything botanical was to be found there.

The walk through the open forest was delightful, and I was happy to be able to check off several species in Gruenteufel, which, since I had discovered the island, could be removed from the sixth edition of the Flora of the Undiscovered Tropical Isles. I observed that certain signs along the way indicated human habitation. One such sign, for example, was a pair of pictographs resembling a fork and knife rendered in white on a blue background, with an arrow pointing to the right. With natural curiosity directing us, we decided to follow the arrow, and soon found ourselves in a clearing around which were arranged a number of huts, on each of which was a sign bearing the image of some sort of comestible—a pig was roasting at the sign of the pig, at the sign of the pineapple a pineapple was turning on a spit, and so on. Presiding over them all was what I guessed must be the chief’s hut: it was a good bit larger than the rest, with a tall wicker dome reminiscent of that on the Basilica of St. Peter at Rome, and a prominent portico whose roof was supported by palm-trunk columns terminating in palm-frond capitals with the fronds turned down into a very passable rendition of Ionic volutes.

Making our way to that splendid edifice, we made our presence known and were greeted by the chief himself, whom we recognized at once by the superior height of his top hat, which was artistically woven from grass and feathers. I found that he spoke a dialect that was very close to pure classical Polynesian, so that we were able to understand each other perfectly; furthermore, he was the very model of affability and good breeding. He told me his name, which was Hunter of Musk-Ox on the Frozen Tundra (a family name whose meaning had been lost in the mists of antiquity), and politely asked mine. But when I told him my name was Milo Pettigrew, he was speechless with astonishment, and it took him some time to recover his normal loquacity, during which I wondered whether I had inadvertently committed some dreadful trespass against local etiquette.

“But that us the name of our island!” he said at last. “Mai-lo-pe-ti-ga-ru!” Then he laughed heartily, and I joined him. It was indeed a remarkably amusing coincidence, but not altogether, when I thought about it, a surprising name for an island. In the more refined dialects of classical Polynesian, the phrase Mai-lo-pe-ti-ga-ru may be roughly translated “Prime Beachfront Real Estate.”

That is the story of how I came to discover the island that still bears my name to this day. While our ship was undergoing the necessary duct-taping for several days, I was able to check off all the plants in Gruenteufel that grew on this now-discovered island, so that Prof. Gruenteufel was able to publish a considerably thinner sixth edition. I also showed the chief how he might profit by setting up a nursery to grow the native species of tropical plants, hitherto unseen in the civilized world, and sell them to the luxury horticultural trade; so that now Milo Pettigrew Island is the only island in the South Pacific inhabited entirely by millionaires. I have not visited personally since our ship, resplendent in its new hull of bright silver duct tape, pushed off from the beach; but from travelers’ reports I understand that there is a somewhat unflattering statue of me outside the entrance to the chief’s hut, which now covers eighteen acres and is built of imported Italian marble.

A NAME FOR EVERYTHING.

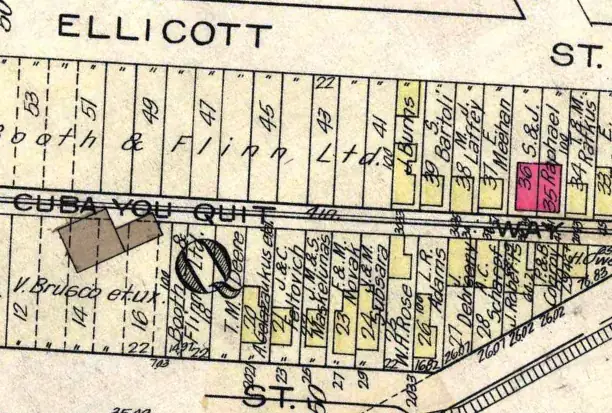

Long-time readers have probably already answered correctly that they are all places in western Pennsylvania.

We have not even ventured into the eastern half of the state, where we also find Dublin and Belfast and Bangor, and Lancaster and Reading and York and Shrewsbury, and Hanover and Hamburg and Heidelberg, and Bethlehem and Nazareth and Emmaus, and even the New Jerusalem.

Also in the east we find a Wyoming Valley. And it may surprise Westerners to discover that the state of Wyoming—this is absolutely true, and you can look it up for yourself—was named for the Wyoming Valley in Pennsylvania, because their new home reminded the early settlers so much of Scranton. (It is an even more remarkable fact that the populations of the two Wyomings, the state in the West and the Scranton metropolitan area, are nearly identical, and you can look that up, too.)

This subject came up the other day when one of Dr. Boli’s frequent readers was remarking on the names of places in Pennsylvania. Her hypothesis was that the name of any conceivable place can also be found somewhere in Pennsylvania.

So far Dr. Boli has had a hard time disproving this hypothesis.

This is true in spite of Pennsylvania’s well-known habit of recycling names for townships. You must give the name of its county with the name of the township, so that when you mention Elizabeth Township, Allegheny County, Pennsylvania, nobody thinks you mean Elizabeth Township, Lancaster County, Pennsylvania. There is also no rule against recycling names in city neighborhoods, so there is an Allentown in the eastern part of the state and an Allentown in Pittsburgh, and yes it does cause confusion every day.

It is also true in spite of the fact that Pennsylvania is notorious for names that occur nowhere else, and could not occur to a sane mind, from Acmetonia to Zelienople. A little education is a dangerous thing in a town founder. What shall we call our new oil boomtown? think the fathers of a new settlement. There is already an Oil City in the Pennsylvania oil country—but there is no Oleopolis. Well, there is now! And now that those two names are both taken, well, there’s always Petrolia.

And it is also true in spite of the Pennsylvanian predilection for abstract concepts as names of towns. Industry, Economy, Prosperity, Amity, Freedom, Harmony, Pleasant Unity—all these abstractions are also places in western Pennsylvania.

In spite of all these things, Pennsylvania is stuffed with familiar names in unfamiliar contexts. The graduates of California University and Indiana University will tell you that they always have some explaining to do. When Pennsylvanians want to make distinctions, they have to be very specific: for example, Pittsburghers will refer to Washington, Pennsylvania, as “Little Worshington” to distinguish it from the District of Columbia. (On the other hand, once you get close enough to Little Worshington, then it is just Worshington, and the District of Columbia is Big Worshington.)

This seems like a good project to turn the readers loose on. Get out your maps. Which famous cities and places can you not find in Pennsylvania? And which names pop up that you didn’t expect to find there? And finally, what is your favorite unlikely Pennsylvania name, and can you do better than “Punxsutawney”?

ANOTHER WAY.

WAYS AND MEANINGS.

It has occurred to Dr. Boli more than once that the standards for naming these “ways” are different from the standards for naming streets. Street names usually have to have some marginal attachment to meaning. Sometimes there is a theme: the Mexican War Streets, for example, are so called because they are named for battles in the Mexican War; the streets in Bellevue are named for Civil War generals; the streets in West View are named for universities and colleges; and so on. Sometimes streets are named for trees or flowers. Sometimes they are named for things that used to be there, like an old estate on which a city neighborhood was built.

But “ways” seem to be named as often as not by flipping open a dictionary or encyclopedia at random and pointing at a word blindfolded. Here, in no order at all, is a list of “ways” in Pittsburgh whose names have at various times struck Dr. Boli as odd or amusing:

Woolslayer Way

Cabinet Way

Lycurgus Way

Asteroid Way

Sewer Way

Pitcher Way

Crooked Way

Gypsum Way

Equator Way

Comet Way

Fred Way

Urn Way

Telegraph Way

Vanilla Way

Relic Way

Livery Way

Alhambra Way

Asterisk Way

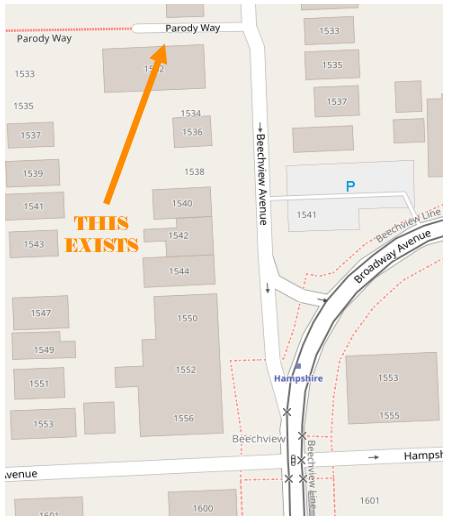

Parody Way

Archon Way

Alcove Way

Lunar Way

Pandora Way

Appian Way

Plummet Way

Revision Way

Highnote Way

Investor Way

Pontoon Way

Minor Way

Repeal Way

Petite Way

Caress Way

Rope Way

Brim Way

Press Way

Boer Way

Saturn Way

Cameo Way

Betty Jane Ralph Way

Quartz Way

Legion Way

Now, for the sake of absolute honesty, Dr. Boli will note that one of those odd names has a foundation in history. Rope Way was a rope walk two hundred years ago: a rope factory was set up next to it, and a long straightway was necessary for pulling the strands straight and twisting them together. Perhaps some of these other ways have similar histories: perhaps they ran past manufactories of asteroids or betty jane ralphs. But Dr. Boli does not know those histories, so the names remain inexplicable to him.

THIS STREET EXISTS.

© OpenStreetMap contributors. Licensed under the Open Data Commons Open Database License.

This is strict truth, because Dr. Boli considers April Fool’s Day the most sacred holiday of the year.

BUCKET LIST.

Five Famous Buckets You Must See Before You Die.

The Old Oaken Bucket, located at the Woodworth House in Scituate, Massachusetts, inspired the famous song by Samuel Woodworth——

The old oaken bucket, the iron-bound bucket,

The moss-covered bucket which hung in the well.

This remains one of the most famous songs ever written about a bucket.

The Devil’s Bucket, northeast of Dead Armadillo, Texas, is a hole in the ground, approximately twelve feet in diameter, whose shape gives it an uncanny resemblance to a large bucket.

King Ethelbeard’s Bucket, a large golden vessel encrusted with precious stones and elaborate Saxon filigree work, is used by Queen Elizabeth to water her petunias. It may be viewed by the public at Buckingham Palace every year on Bucket Day.

The Amazing Farmer’s Bucket Theme Park in Qianxinan Buyei, China, has as its centerpiece a three-hundred-foot-tall mechanical figure of a farmer carrying a bucket. Riders ascend an elevator to the shoulder and slide down the interior of the arm into the bucket, and the “farmer” dumps them on his “garden.”

The George Jasnorzewski Memorial Bucket Truck in Grant Borough is used every year to place the Christmas decorations on the borough building. It is named for Mr. Jasnorzewski, who tragically died at his desk in the borough building while filling out the requisition forms for a bucket truck.

COLORFUL LOCAL TRADITIONS.

Probably not in South Africa.

—

In Porto-Novo, Benin, laundry cannot be hung out to dry until it is blessed by the Archbishop.

Any resident of Coosawhatchie, South Carolina, who ambles across the highway in less than four and a half minutes is socially ostracized and has to move to Ridgeland.

In Cleveland, every April 1, traffic police amuse residents by enforcing the no left turn signs.

Capes are seldom worn in Cape Town.

In New Delhi, it is customary to give cabinet ministers gifts of socks with gold clocks in the hope of favorably influencing their decisions. It never works.

When a freshly married couple in Yoshinogawa, Japan, reach their new abode, the bride is carried across the threshold by an Amazon Prime delivery driver.

It is considered poor manners to wave frantically with the left hand while falling from a tall building in Dubai.

PITTSBURGH TOPOGRAPHY EXPLAINED IN ONE PICTURE.

A VERY POETIC TELLER MACHINE AT THE VATICAN.

Photo of a Vatican City teller machine by Seth Schoen, who has released it under the Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 2.0 Generic license.

—

In one country in the world, you can use a teller machine in Latin, which makes Dr. Boli happy. The Google translation of the words on screen (click on the photo to enlarge it) makes him even happier. Dr. Boli knows that Google Translate’s Latin translations tend toward the surreal, so he had to find out what Google had to say in this case. Dr. Boli interpreted “Inserito scidulam quaeso ut faciundam cognoscas rationem” as something like “Please insert card for operating instructions.” But Google interprets it as “I beg you to do anything you know them to the character of a card inside the mouth.” That is much more poetic than Dr. Boli’s interpretation.

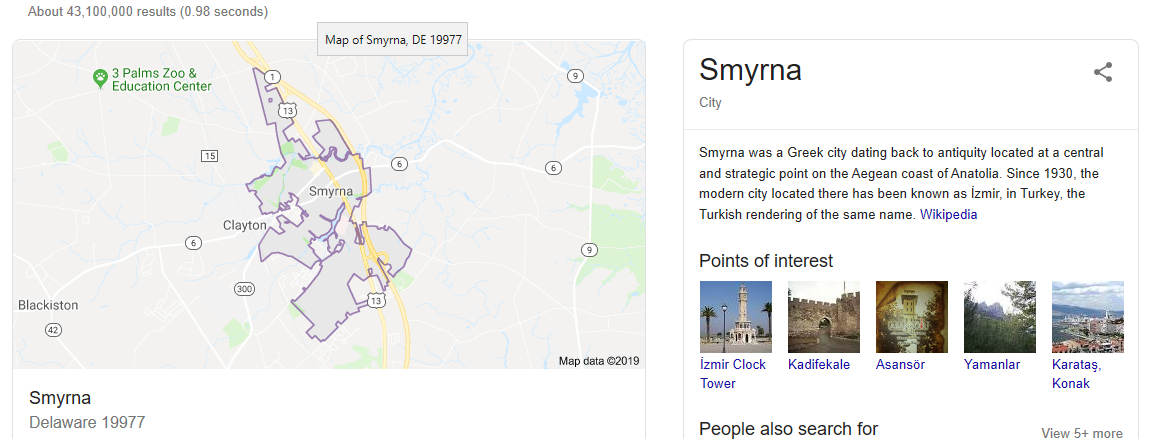

SMYRNA.

IF YOU LOOK up “Smyrna” in Google, you get a little box with the beginning of the Wikipedia article: “Smyrna (Ancient Greek: Σμύρνη, Smýrnē or Σμύρνα, Smýrna) was a Greek city dating back to antiquity located at a central and strategic point on the Aegean coast of Anatolia.” And you get a map of Smyrna and its suburb Clayton and the 3 Palms Zoo & Education Center.