Posts filed under “Travel”

SOMETIMES LIFE IS A CARTOON.

MORE ON GEOGRAPHICAL NAMES.

Martin the Mess writes, on the subject of French-derived place names, “Here in Illinois, we infamously mispronounce most of our French-derived placenames, such as Versailles (Ver-SAYLES), Des Plaines (DESS-Playnes), and Cairo (KAY-Row). I know the last one there is technically not French, but we manage to blame them for our mangling of it nonetheless.”

There is a borough of Ver-SAYLES on the Youghiogheny just outside McKeesport, and it is likely that there are many others in the United States. But Dr. Boli does not regard “Ver-SAYLES” as a mispronunciation. Famous foreign places have English names—Rome (not Roma), Moscow (not Москва), Munich (not München), Athens (not Αθήνα or Ἀθῆναι), and so on. As we become more ignorant of foreign places, we lose those native English names for them one by one, and have to go back to the foreign names when we do want to talk about them.

One of the more recent losses is Marseilles, so spelled (and pronounced “Mar-SAYLES”) until well past the middle of the twentieth century. A Merriam-Webster Geographical Dictionary from 1966 gives “Marseilles” as the only recognized spelling in English, and “Mar-SAYLES” as the only recognized pronunciation. Now, of course, you will be either politely corrected or snobbishly derided if you use the English spelling and pronunciation.

The same thing happens with foreign personal names. Who recognizes the name “Tully” today? We must say “Marcus Tullius Cicero” if we are to be understood. Yet the use of the correct Latin form is not a sign of better education, but of darker ignorance. Tully had an English name because he was a subject of everyday conversation in English.

Thus we may take the persistence of an English name for a foreign place as an indication that English speakers can still imagine that place as actually existing and potentially worth talking about, whereas foreign places that have lost their English names are at best unsubstantiated geographical rumors.

Local traditions, however, are more stubborn, and the English pronunciations of many foreign names are preserved in places like Ver-SAYLES and CAY-ro. You will not be able to extinguish the persistent belief that those names are “pronounced wrong,” but fortunately you will not be able to extinguish the pronunciation, either.

There is still no excuse for DESS-Playnes.

AN ARCHITECTURAL ABSURDITY.

If you are not from Pittsburgh, there is a good chance you will not believe that this building exists. If you are from Pittsburgh, you may still not believe it. In fact, it is literally invisible to many people, even when they stand right in front of it, until it is pointed out to them: the human brain does not have a category for a building of these dimensions. This is the Skinny Building, which is eighty feet long and exactly five feet two inches deep. It has recently been restored to its Victorian glory, so our friend Father Pitt provided us with this picture.

LET’S VISIT CANADA.

The Vancouver El, photographed by Tim Adams.

—

Part 11.—What to See in British Columbia.

British Columbia, separated as it is from the rest of Canada by a broad swath of mythological territory, is rather different from the other civilized provinces. For some time in the earlier years of the automobile, for example, British Columbians drove on the left, while the rest of Canada drove on the right. The province is now officially right-hand-driving; but to this day, many drivers in Vancouver maintain the earlier tradition.

Vancouver, the metropolis of British Columbia, is famous for playing nearly every other city on earth in the movies. If you see a movie whose story is set in New York, Chicago, Toronto, Boston, Paris, Washington, Baltimore, Addis Ababa, or New Orleans, it was probably filmed in either Vancouver or Pittsburgh. If you see a movie set in Pittsburgh, it was almost certainly filmed in Vancouver; and if you see a movie set in Vancouver, it was almost certainly filmed in Pittsburgh. In this way Hollywood maintains its famous budgetary efficiency.

Vancouver has an elevated rapid-transit system much like that in Chicago or the Market-Frankford Line in Philadelphia. The authorities in Vancouver, however, have made the useful discovery that, whereas calling the system an el (as in Philadelphia) or an L (as in Chicago) makes it old and rattly and unattractive, calling it a SkyTrain makes it futuristic and modern and Disneyish. Branding is the key to success in any endeavor.

Victoria, the capital of British Columbia, has registered the word “quaint” as a trademark in Canada, and actively protects its intellectual property.

The Queen Charlotte Islands, famous for their scenery and culture, were officially renamed Haida Gwaii as part of an agreement with the First Nations inhabitants acknowledging their centuries of mistreatment by European settlers and their descendants. In return for the renaming, the Haida agreed not to expect too much in the way of anything actually worth money.

The mountains of British Columbia are tall, snow-capped, and awe-inspiring, and best seen from a distance, which can be accomplished from Vancouver without straying too far from the nearest Starbucks.

The interior of British Columbia is inhabited by large numbers of grizzly bears, which are tame, friendly, and lovable critters that enjoy a good cuddle, according to a government brochure published under the Tourist Reduction Act of 2012.

LET’S VISIT CANADA.

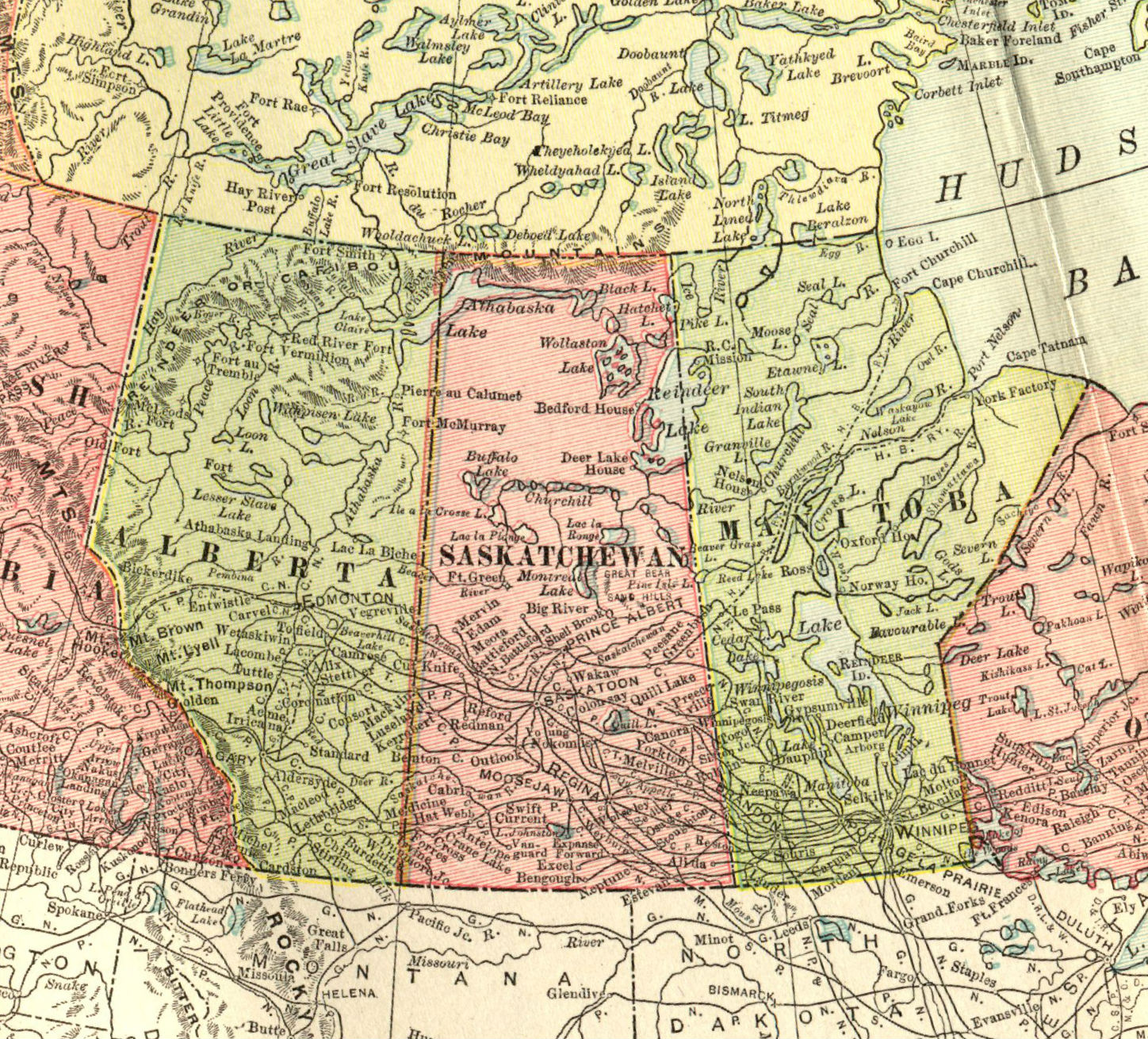

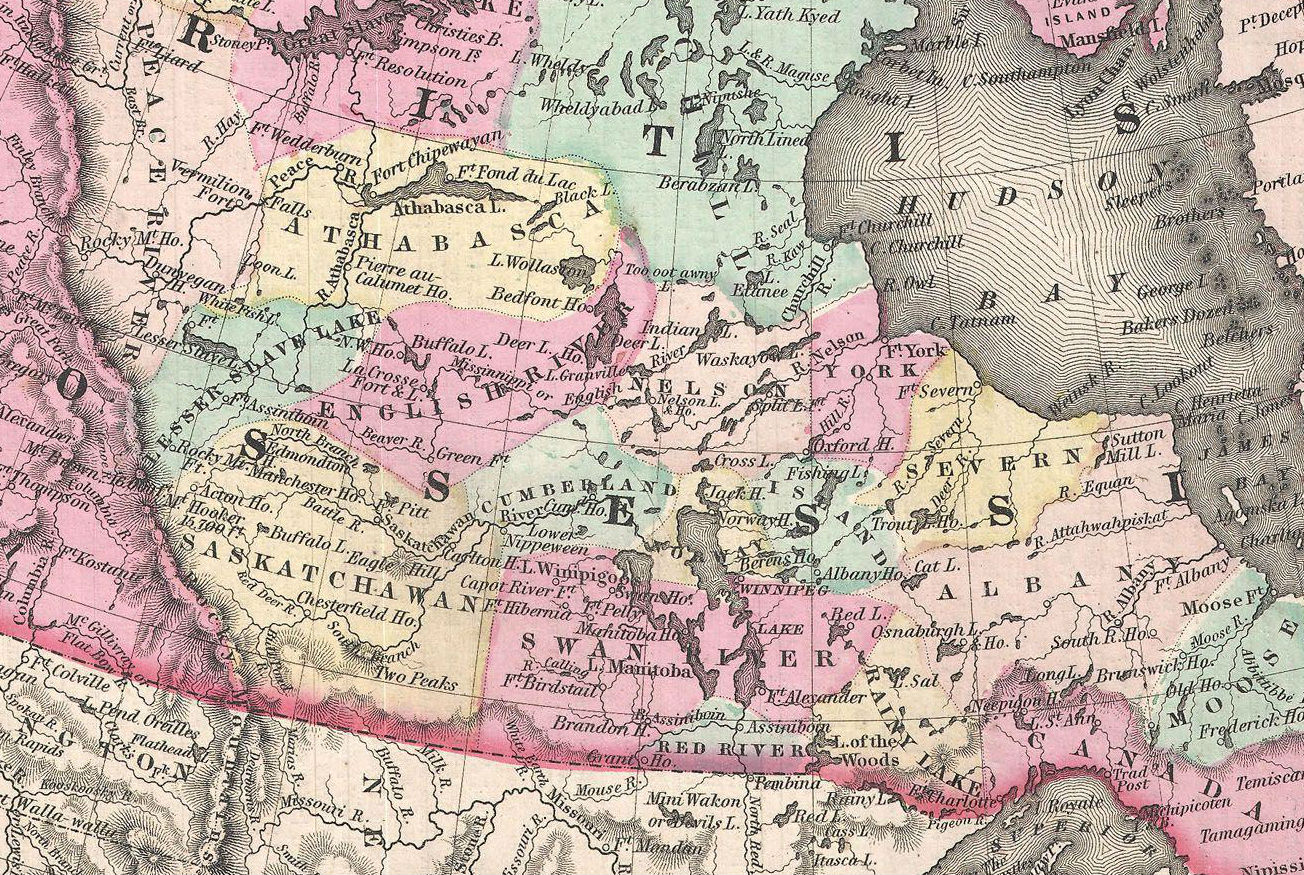

Part 10.—What to See in Albatchetoba.

Between Ontario and British Columbia is a large stretch of uncharted territory in which cartographers have felt free to impose their wildest geographic fantasies on the landscape. No two of them come up with anything like the same idea, which is what makes geography such a creative science.

Most information about this part of Canada is similarly fictional. For example, a favorite inside joke among geographers on lecture tours is to speak of a city called “Saskatoon,” laboriously maintaining a serene countenance, until at last the lecturer breaks down into uncontrollable giggles, and the imposition is revealed.

The capital of Albatchetoba is Reginald, or possibly Winifred or Edward, home of the famous Canadian Museum for Human Rights, where all the human rights Canadians have fought for over their long and heroic history are embalmed in jars for public display. Tourists will also be enchanted by the National Museum of Grass, a celebration of the family of plants that made the prairie the endless dull slog it is.

Banff National Park is visited every year by millions of tourists lured by pictures of impossibly beautiful mountain landscapes, which are provided by a series of matte paintings, some of the largest in the world outside Hollywood.

The principal mammals of the Albatchetoban forest are unicorns, which are abundant in the woods and rapidly encroaching on the suburbs. Adult unicorns have no natural enemies, but the young sometimes fall prey to the Albatchetoban Flying Lynx.

LET’S VISIT CANADA.

Part 9.—What to See in Ontario.

Ontario is Canada’s most populous province, although, as with Quebec, we must remember that the “populous” part is crammed into an area about the size of New Jersey, leaving an area about the size of China to the wandering moose.

The main thing to see in Ontario is Niagara Falls, which was cleverly created by God (a notorious Canada-sympathizer) to suck U. S. tourists across the border to buy souvenir keychains. The thing about Niagara Falls is that you can hear it from New York, but you can really see it only from Ontario. Millions of tourists who say they have been to Canada have never stepped outside the part of Niagara Falls devoted to the themed-indoor-miniature-golf industry.

That is a pity, because if they stepped even a few yards out of that zone, they would discover that much of the rest of the Niagara peninsula is filled with memorials (such as the Brock Monument, above) to Canada’s glorious victory in the War of 1812. Now, every American schoolchild knows that the War of 1812 was really a glorious victory for the United States, in the sense that we did not actually lose anything other than human lives and the city of Washington, which are both expendable; but the polite visitor will refrain from disillusioning his Canadian neighbors. A drive along the border will open the tourist’s eyes to the remarkable number of fortifications that were erected for the purpose of keeping out Yankee invaders. Most of them have now been repurposed as souvenir-keychain emporia.

Toronto is the greatest metropolis in Canada, notable especially for its streetcars. Seven cities in North America never entirely abandoned streetcars (the others being Boston, Philadelphia, Pittsburgh, Cleveland, New Orleans, and San Francisco); in Toronto’s case it was thanks largely to one stubborn transit official, who wielded such power in his domain that he could resist the diesel tide that overwhelmed other municipal transit systems. This is a strong argument in favor of the feudal system. Toronto is also the home of the CN Tower, the tallest free-standing structure in the Western Hemisphere (sorry, New York), which is placed so as to give the Toronto skyline the look of a Star Trek matte painting.

Ottawa is the capital of Canada, and is therefore most notable as the best place to see majestic herds of members of Parliament in their native environment. Be sure to stop in and say hello to the Governor General, dropping off any hats you may wish to forward to Queen Elizabeth. The Governor General will of course present you with a challenge to prove your sincerity, which is why you brought those xylophone mallets.

The Thousand Islands are severely undercounted.

THE WAY WE LIVE NOW.

Photo by Wikimedia Commons user BenFrantzDale. GNU Free Documentation License.

An interesting observation on the changes wrought by the last quarter-century:

Consider the photographs of Reversing Falls in our recent article on New Brunswick. If you look closely, you may notice a bit of reflection, especially in the last picture (reproduced above), suggesting that the photographer was inside a building.

What building was it? you might ask yourself. Dr. Boli asked himself that question. It has been some years since he was in Saint John; he recognized the vantage point immediately, but could not remember the building.

How would you have answered that question in 1990? You might have gone to the central library, if you lived in a large city, and enlisted the help of a reference librarian, who might (if you were lucky and your library was unusually well stocked) have found you a map and a telephone directory of Saint John; if you had been extraordinarily clever, you might have been able to find the approximate address on the map, and then somehow, with a number of lucky deductions, found that address in the directory. How long would that take?

Streetcar and bus to library: 45 minutes

Conversation with librarian: 15 minutes

Poring over map: 5 minutes

Trying to find a specific address in the Saint John telephone directory: several hours

Thinking realistically, would you have done all that just to find the answer to your question? Almost certainly not; you would have left the question unanswered, reasoning that your idle curiosity was not worth a whole afternoon of work.

Let us leap forward now to the futuristic world of 2015. You ask yourself the same question. You call up a map of Saint John on Google Maps. You find the building in the satellite view. You plunk yourself in front of it in Street View. You see that it is a sushi restaurant called Boaz West. Time elapsed: less than a minute.

We often hear that the Internet is making profound changes in the way we deal with information, but because the changes are incremental, we seldom pause to think of them. Here is an opportunity to pause and think and ask ourselves what it all means.

LET’S VISIT CANADA.

The Château Frontenac, Quebec City, by Bernard Gagnon (CC BY-SA 4.0).

—

Part 8.—What to See in Quebec.

Quebec is not exactly like anything else in the world. It is not exactly a province; where other Canadian provinces have provincial parliaments, Quebec has an Assemblée nationale, a National Assembly. Yet it is not exactly a nation, since it is part of the federation of Canada. Yet it is not exactly part of the federation of Canada, since it has never accepted large parts of the Canadian constitution, which it regards as foisted on Quebec against its will; and, furthermore, under the doctrine Gérin-Lajoie, Quebec asserts the right to make treaties with foreign powers independently of the rest of Canada. Yet its citizens, in referenda, have repeatedly rejected attempts to separate Quebec from the Canadian confederation. It is therefore probably safest to describe Quebec as a state of mind.

Since so much of the politics of Quebec involves stamping out English in public and paranoid ranting about the various threats to la Francophonie posed by encroaching Anglophonism, the U. S. tourist will probably assume that the Québécois would be universally hostile to Americans who cannot speak French, and will spend months honing his conversational-French skills before heading for Montreal. And then he will find it impossible to use them. Every Francophone Québécois will instantly recognize him as a tourist from south of the border and insist on speaking to him in perfect English. In every shop, restaurant, hotel, subway entrance, gas station, or tourist attraction, he will attempt to start a conversation in French, only to have it instantly diverted to English by the smiling and polite Québécois. One suspects it is some sort of national joke.

Montreal is the great metropolis of Quebec, and the greatest French-speaking city outside Metropolitan France. It is also the only Francophone city in the world with an American baseball team, so it is really the only place to go if you have always cherished a secret fantasy of shouting at an umpire in French. It has subways and commuter trains and crowds and appalling traffic and everything else you want from a great metropolis. If you wish you could visit Paris but can’t stand the sight of the Eiffel Tower, Montreal is the place for you. La Ville Souterraine, the Underground City, is the world’s largest underground complex, which makes it the perfect destination for a tourist who wishes to visit an entire city without setting foot in the grubby outdoors. Indeed, Montreal is perhaps the only city in North America made of equal parts old-world charm and dystopian science fiction.

Quebec, the provincial capital, is the only European walled city in North America north of Mexico; it looks a bit like the cover art for an alternate-history fantasy novel. The Citadelle, a star fort in the middle of the city, is officially a residence of the Queen of Canada, but no one ever sees her taking out the trash, and rumor has it that she may not live there at all.

The Hôtel de Glace is a hotel made of ice outside Quebec City. Every winter it is painstakingly rebuilt over the frozen corpses of last year’s guests.

Saguenay is the home of the Ha! Ha! Pyramid (Pyramide des Ha! Ha!), a jolly and whimsical memorial to the most destructive flood in Canadian history.

The rest of Quebec is made of tundra and French-speaking moose and mosquitoes big enough to be mistaken for musk oxen. About 5% of Quebec is civilized; the rest tends to show up on maps with engravings of dragons instead of railroads and highways.

Tourists who drive should note that stop signs in Quebec usually say “ARRÊT.” That is especially confusing to drivers from France, where stop signs say “STOP.”

LET’S VISIT CANADA.

Saint John, the great metropolis of New Brunswick.

—

Part 7.—What to See in New Brunswick.

New Brunswick, or le Nouveau-Brunswick, is Canada’s only officially bilingual province, with Acadian French speakers making up about a third of the population. Many U. S. visitors are surprised to learn that; they would have guessed that Quebec was bilingual, but in fact Quebec has been officially French-only since 1969 and thinks its English-speaking residents should go stick their heads in properly sized individual buckets of water. Like everything else of purely local interest, the bilingual status of New Brunswick is enshrined in the Canadian constitution, which also specifies the dimensions of the buckets of water in which Anglophone Quebecers are to stick their heads.

New Brunswick was founded as a refuge for American loyalists who fled the new United States after the Revolutionary War. The founders meant to show those rebels a thing or two by setting up a colony that would be “the envy of the American states”; and indeed, at its current rate of growth, the population of New Brunswick may soon surpass the population of greater Dayton. Mission accomplished.

The most important attraction in New Brunswick is Magnetic Hill, one of earth’s most mysterious places. At Magnetic Hill, just outside the city of Moncton, you stop your car at the top of the hill and put the transmission in neutral, and then the car rolls down the hill by itself as if attracted by a mysterious invisible force. At the bottom of the hill is a large souvenir-keychain emporium.

Fueled by the souvenir-keychain industry, Moncton has become the largest metropolitan area in New Brunswick. But there is nothing to see in Moncton except miles of keychain factories and the gleaming new glass-walled headquarters buildings of the international keychain conglomerates, so we move on to the real city in New Brunswick.

Saint John, until recently the largest metropolis of New Brunswick, is home to Reversing Falls, a fascinating phenomenon in which the raging rapids on the Saint John River actually change their direction of flow. The moment of transition is tremendously exciting, as you can see from this series of photographs:

Inbound Flow.

Transition.

Outbound Flow.

Photos by Wikimedia Commons user BenFrantzDale. GNU Free Documentation License.

Saint John was also the place where the great Henry Burr was discovered, and anyone who, like Dr. Boli, still has a large collection of acoustical phonograph records will wish to make a pilgrimage to the Imperial Theatre to pay homage.

Fredericton is the provincial capital, which makes it the place to go if you want to see a bilingual provincial parliament at work. It is not as entertaining as it sounds.

The Bay of Fundy, which separates New Brunswick from Nova Scotia, is famous for having the highest tides in the world. Tourists love to clamber among the Rocks at Hopewell Cape when the tide is out. Then the tide comes in and sweeps them all away, and their mangled corpses are picked up on Cape Cod beaches some weeks later.

Northwestern New Brunswick is an Acadian stronghold, and possibly the only place in Canada where a tourist will not be able to converse with the locals in ordinary English. The surprising number of monolingual Francophones may make it necessary to shout very loudly, which is of course always the key to making oneself understood to people who speak no English.

LET’S VISIT CANADA.

Part 6.—What to See in Prince Edward Island.

Prince Edward Island, the 104th-largest island in the world, is the smallest of Canada’s provinces. It is known to history as the birthplace of Canadian confederation, but fiction trumps history by reminding us that the island was also the location of Anne of Green Gables, which is all anybody cares about.

The population of Prince Edward Island is about 140,000, which puts it slightly below Coeur d’Alene (Idaho) but a little above Homosassa Springs (Florida). This is the winter population, however; in the summer, the population is swollen to several times that figure by masses of Anne of Green Gables fans who swarm to the island to buy souvenir keychains featuring their favorite characters from the book.

Aside from the annual stampede of Anne of Green Gables fandom, the primary attraction of Prince Edward Island is red sand. Parks Canada spends millions of loonies every spring dyeing the sand on the beaches in preparation for summer vacation season. Unless there are large storms or international Anne of Green Gables cosplay conventions, the dye job usually lasts well into the autumn; but by spring the beaches are dull buff-colored again. Casual vacationers seldom think how much effort goes into creating a unique aesthetic environment for their amusement.

Prince Edward Island is also known for the world’s most concentrated collection of octagonal wooden church steeples, and you may make of that what you will.

The island is now linked to mainland New Brunswick by a bridge, which in Dr. Boli’s opinion counts as cheating. If Dr. Boli had to get there by boat, then you young whippersnappers with your horseless carriages should have to take a ferry as well. Yes, Dr. Boli is aware that the bridge was allowed to assume the duties of a steam ferry by a constitutional amendment, but this is just one of many ways in which the Canadian constitution is a sloppy affair.