Now, this is not to say that there are not many other linguistic prejudices in the world. The violent antipathy expressed by many Americans—they usually call themselves “Patriots,” with a capital letter, implying that they constitute an ethnic group—toward hearing Spanish spoken in public is one of the phenomena future historians will probably have to explain, as today’s historians have to explain the violent antipathy that previous generations of Americans expressed toward hearing the Hungarian or German or Italian or Welsh spoken by those Patriots’ ancestors. And this is certainly not a uniquely American phenomenon. Go to Serbia and start a conversation about the Croatian language and see how quickly the responses become unprintable in a polite Magazine such as this one. Ask a Russian about the Ukrainian language, or a Ukrainian about the Rusyn language. Ask a Brooklynite what she thinks of the Boston dialect. Linguistic prejudice will always be a fact until our translation machines are so far advanced that we simply do not know when people are speaking other languages than our own.

But that prejudice is not hardwired into modern culture and technology. If anything, our technology is controlled by people who do their best to counter that prejudice by making any language accessible to everyone else in the world.

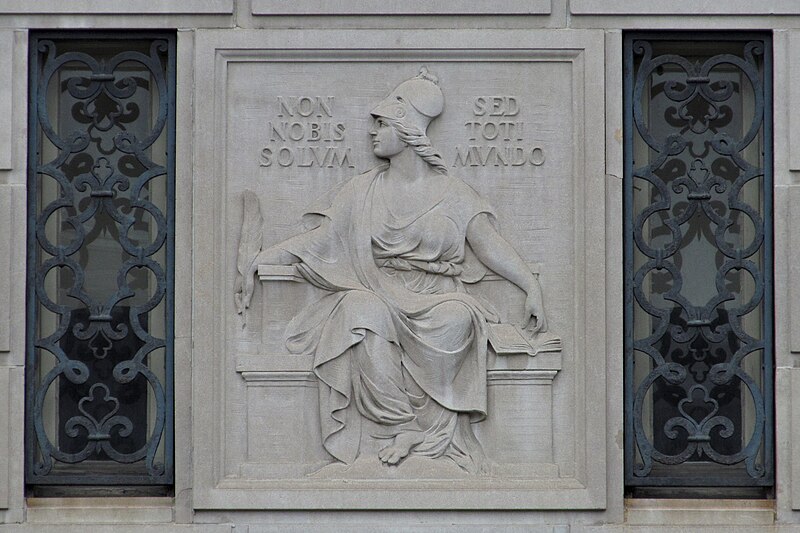

Unless the language is Latin. Then it must be shunned.

For example, we can look at the FLORES+ language dataset. This is a set of language data for evaluating machine translations. It currently includes 222 languages, including Faroese (spoken by about 69,000 people, according to Wikipedia) and Scottish Gaelic (spoken by about 70,000, again according to Wikipedia). It is so obvious that these languages are more important than Latin that it is probably taken as a fact not open for debate.

Perhaps the prejudice is not against Latin per se (to borrow a term from somewhere or other); perhaps it is simply a decision to exclude “dead languages”—languages that are no longer used in everyday speech, though they have a long literary history and are still important to specialists. That would be a defensible position, although it would be odd to say that there is more of a need for Esperanto translation (Esperanto is included in the FLORES+ dataset) than there is for Latin translation. But it wrecks against the fact that Sanskrit is on the list—Sanskrit being a language almost exactly analogous to Latin in its cultural position: a language with centuries of great literature that is still an important tool for scholars today, but not one that is the regular daily speech of any particular ethnic group.

So Latin is unique. The prejudice against it is so pervasive that it is invisible. It is part of the way the world works that of course Latin needs to be ignored and Sanskrit needs to be taken into account. No one questions the assumption because no one notices it.

Why is that?

It is probably because there was a long and successful fight in the Western world, and especially in the English-speaking world, against the use of Latin in general education. Through the nineteenth century, the main purpose of higher education was to leave its students with a competence in the classical languages. Other subjects were optional. This was as true of practical-minded Americans as it was of Europeans: a college education meant an education in Latin and Greek.

As the idea of “progress” took more and more hold on the imaginations of succeeding generations, however, the old ideal of a classical education was held up to more and more ridicule. It was wrong in every way: it was useless, in that you could not easily show how it led to more money; it was elitist, in that it created an elite class who prided themselves on their useless accomplishments; and it was wasting the time of our most intelligent young people, who ought to be learning how steam performs its miracles rather than how Cicero placed his adjectives.

The academic world did not give up the ideal of a classical education without a long struggle. But today it is hard to find a good classics program at a university, or at least we can say—since everything is easy to find in the age of the search engine—that a classics program is an arcane specialty, and one that is often hanging by a thread where it is found.

Yet the struggle is not over, because, like most revolutions, its mythology requires it to beat the dead horse long after its bones are bleached. There is something about the idea of a classical education that still has to be repudiated. Sanskrit did not form part of the traditional classical education in Europe and America, and therefore there is no need to repudiate it. It is safe to allow Sanskrit in our language dataset.

However, after all that, the story does not end with a complete repudiation of Latin. Artificial intelligence is responsible for many embarrassing cultural bloomers, but one of the virtues of the large language models is that they are self-learning. They simply scrape all the information on the Internet and learn what there is to learn. Much of the information is wrong and bad, so they learn wrong and bad things. But also, much of the information is in Latin. And so the best-known chatbots have become very good at translating Latin—not because anybody asked them to become Latin experts, but because the knowledge was there and they grabbed it.

Much research has shown how AI bots reinforce our prejudices, and on the other hand many of our politicians have been complaining that the AI bots do not reinforce their prejudices nearly enough. But—as we saw in the case of poetry—the bots do have the virtue of showing us the real state of human culture divorced from our individual biases. In this case, our human intellectual culture has a huge blind spot—but the bots have learned to see what we refuse to look at.