But if you are still here, you probably noticed that the question in the title is provocative, and perhaps even despairing. Is it possible to write an accurate account of things that happened in the past, or is anything before our own lifetime so far gone from us that we can never understand it?

Dr. Boli is not a pessimist; he believes that good history can be written. But he also believes that it seldom is written, and that there is an unrecognized intellectual assumption current in our own time—an assumption we share with medieval historians—that prevents all but the best historians from writing any history worth reading.

These musings come from a question that Dr. Boli wanted to answer for himself. Is there a complete list of Isham Jones’ songs anywhere? Isham Jones, for the younger people, which is everyone who is not Dr. Boli, was one of the popular songwriters of the 1920s and into the 1930s. You may not know his name, but you have heard “It Had to Be You,” so you know Isham Jones. He had a distinctive way of constructing a melody, of which “It Had to Be You” is a fair specimen: take one short musical phrase, repeat it, transpose it, turn it upside-down and inside-out, and you have a song.

Uniquely among the top songwriters of the 1920s, Isham Jones was also a bandleader. He led his orchestra until the middle 1930s, when he decided to retire and live on the royalties from his songs. The orchestra continued under his young singer and reed player Woody Herman, and some of the young folks may be old enough to remember Woody Herman’s band, which was still playing into the 1980s.

All this is preface to explain what Dr. Boli was looking for when he landed on this ad-laden page at “SecondHand Songs,” a site devoted to sorting out cover versions from the original songs. And the fact that Isham Jones appears in this site at all shows a complete misunderstanding of the music business in the 1920s. But it is a misunderstanding that is so universal that there seems to be no correcting it. The truth is so far beyond the imagination of current music lovers that the past must be altered to conform to the norms of the present.

In the twenty-first century, a “song” is associated with a particular performer. If Beyoncé releases a recording, that song was probably written for her in particular. If it was not—if it was written for a different performer—then Beyoncé’s recording is a “cover version,” defined by Wikipedia as “a new performance or recording by a musician other than the original performer or composer of the song.”

Of course this definition makes the unexamined assumption that there is an “original” performer of a song.

That was not true in the 1920s. Song-publishing was a big business, and song publishers expected to make most of their money from sheet-music sales. So a song was written for everybody. It was not written for one particular performer any more than a novel was written for one particular reader.(1) The sheet music was scored for piano accompaniment, because just about everybody had access to a piano, but usually it also had ukulele or guitar chords.

When a song was published, if it was by a well-known songwriter like Isham Jones, every big and small musical group across the country would be expected to play it. Remember that recordings were not the main way music was consumed, even though records were a big business: it was actually true that, if you walked into a large restaurant, there would be live musicians right there, in the restaurant, playing the latest songs. Dancing was big business. Nightclubs were everywhere. Speakeasies had small jazz bands.

As for recordings, the same principle applied. Every record company would record the new song. Often there would be more than one recording from the same company. A famous singer might record a vocal version with only piano accompaniment, or with a small group. Then a dance band might be brought in to record an instrumental dance version of the song, or a dance version with one chorus of vocal. If it was a record company that had a line of “race records,” a Black jazz band might be brought in to record the song for that market.

Now, which of these records is the “original” and which the “covers”? Obviously those categories do not apply. They assume a completely different business model.

So, with that introduction, go back to the Isham Jones page at “SecondHand Songs” and admire the amount of painstaking research that went into determining which was the “original” version of each song and which were the “covers.” Dr. Boli does not know what criteria were used to make these determinations—only that, whatever the criteria, the determinations are wrong, because the categories do not apply to the songs in question.

But the misunderstanding is universal, and it is part of a complex of misunderstandings that show the conditions of a later era being projected back on the 1920s. Look at the Wikipedia article on Isham Jones. In the list of compositions by Jones, we see several noted as “number 2 single for year 1925,” and so on. Whose version was the popular one? And what does “single” mean? In 1925, a confused record-company executive would probably have told you that it was a double, not a single, because there was another recording on the other side. (Some high-class records, like some of Caruso’s, really were single: they were released with only one side, the other being completely blank.) “Single” became a meaningful distinction only when the LP record came on the market, which was in 1948.

The Wikipedia article on “cover version” is even more dismaying, because it shows the work of someone who has put a great deal of effort and thought into sorting out the history of cover versions, but has unknowingly brought all the assumptions of his own era with him into the past. (You will note that the article carries the “needs additional citations” template, because for paragraphs at a time there are no citations at all.)

Early in the 20th century it became common for phonograph record labels to have singers or musicians “cover” a commercially successful “hit” tune by recording a version for their own label in hopes of cashing in on the tune’s success. For example, Ain’t She Sweet was popularized in 1927 by Eddie Cantor (on stage) and by Ben Bernie and Gene Austin (on record), was repopularized through popular recordings by Mr. Goon Bones & Mr. Ford and Pearl Bailey in 1949, and later still revived as 33 1/3 and 45 RPM records by the Beatles in 1964.

Because little promotion or advertising was done in the early days of record production, other than at the local music hall or music store, the average buyer purchasing a new record usually asked for the tune, not the artist. Record distribution was highly localized, so a locally popular artist could quickly record a version of a hit song from another area and reach an audience before the version by the artist(s) who first introduced the tune, and highly competitive record companies were quick to take advantage of this.

This is almost all unsourced, almost certainly because it comes from the writer’s own observations of the music of the past, and his own deep cogitation and consideration of the causes of the phenomena he observed. But he did his research mostly among records. If he had looked in old magazines, for example, he would not have written that “little promotion or advertising was done in the early days of record production.”

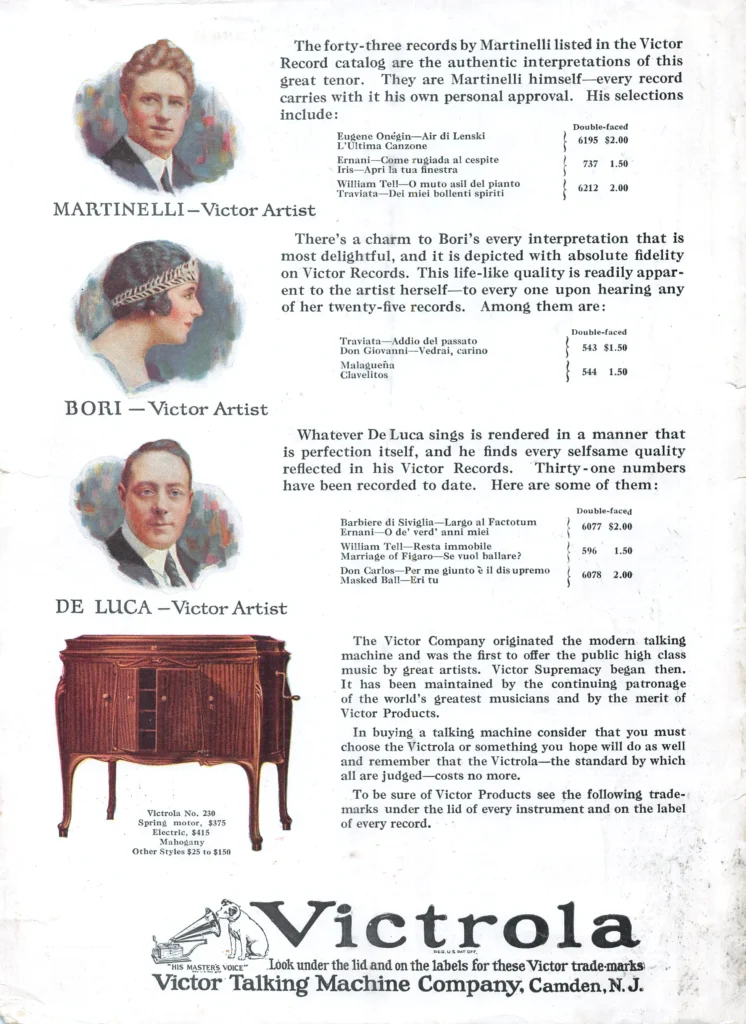

This advertisement was the entire back page of Popular Science for November, 1923—the most expensive ad in the magazine.

It reminds Dr. Boli of medieval historians, who unconsciously imagined the ancient world as a feudal society full of medieval lords and knights, because they could not imagine a world that was organized on any other principle.

And can any historian do better than that? Can any historian do more than observe the phenomena of the past, and then try to figure out what caused them to be the way they were?

Well, yes. You can do more. You can live in the past. Now, Dr. Boli admits that he has a certain advantage here, but his advantage disappears when we speak of the more remote past. There he is in the same boat as all the other historians. But he does not mean that only old people can write history. What he does mean is that a historian should spend a long time immersed in the details of the past.

For example, a writer trying to write a history of music in the 1920s must realize that recordings are only a tiny bit of the history. Popular magazines, newspaper advertisements, novels, and movies will give us a broader picture. You see the scenes in the movies of people dancing in restaurants, and realize that people used to do that—and therefore there must have been music. You read the scene in the novel where the heroine picks up a song and sits down at the piano to play it, and realize that, to her, “a song” meant something printed on paper. You see the ads in magazines from song publishers and see that their songs were available in arrangements for popular orchestra, and realize that every musical agglomeration across the country could buy that song and play it, as thousands must have done or the ads would not have paid. You read the debates in music magazines over whether those “stock arrangements” are adequate for a high-class band, or whether a really good orchestra should have its own arranger to do “specials.” If your eyes are open and your brain swept free of assumptions, you begin to get a picture of how those unaccountable people of the past actually lived.

That is what Dr. Boli means by living in the past. Before you set finger to keyboard, you must spend some time wallowing in the original sources. Not only the great figures of the time: they certainly are important, but they are by definition outliers, women and men whose minds went beyond the temporary assumptions of their era. Immerse yourself in the ordinary. Pile up heaps of ephemera. Live the intellectual life that the ordinary citizens of the past lived, and you will begin to understand the world they lived in.

And then you can come back to our own world and rewrite the Wikipedia article on “cover version.”

Footnotes

- There are exceptions to this blanket statement, of course. A popular vaudeville performer might have a particular comic song written for her, for example, and of course Broadway musicals had songs written for the characters in those musicals. But, with rare exceptions, even Broadway songs were written with the assumption that anybody might perform them; the show might outlast the cast, and if it was any good the songs would take on lives of their own. If they did, everybody performed them and everybody recorded them. It is also true that jazz bands might develop their own specialty instrumentals, and they might trade those arrangements with other jazz bands; in those cases it might be legitimate to call one recording the “original” and others “covers.” (↩)