Posts filed under “Art”

ASK DR. BOLI.

This was an interesting question, because Dr. Boli did not know the answer—or at least he did not know the whole answer. Part of the answer was easy. The patterns are not randomly generated: they come from various old books and catalogues. They do often repeat, but you would need a very good memory to recall one specific marbled endpaper.

But to the question of how many there are Dr. Boli did not know the answer, so he set his secretary to counting. Here is the census of backgrounds:

77 marbled endpapers

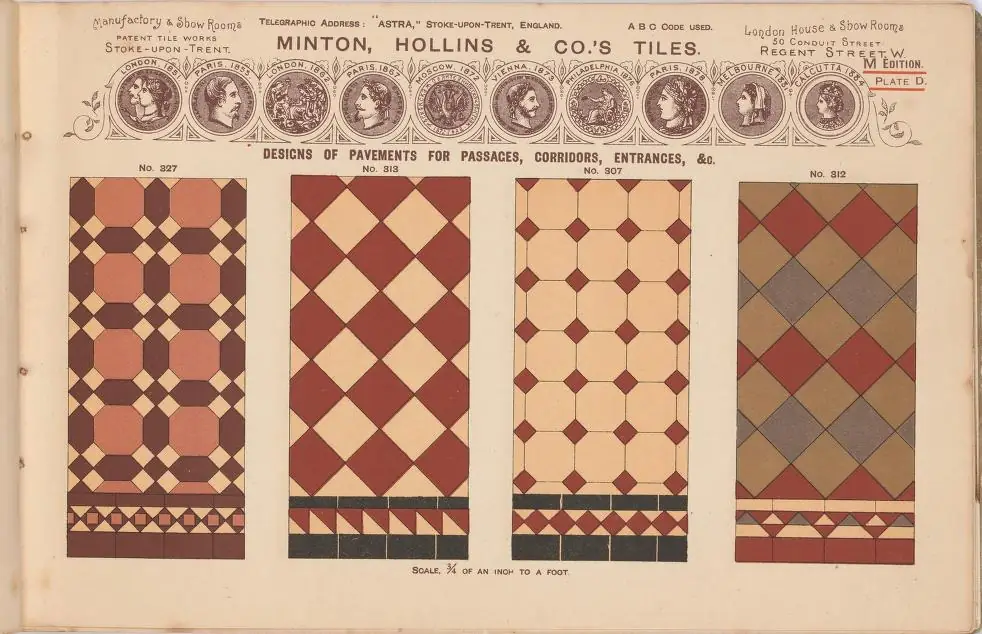

72 tile patterns from various tile manufacturers

48 miscellaneous other backgrounds (such as wallpaper patterns, cloth bindings, fabric prints, and so on)

That makes a total of 197 different backgrounds so far, which is enough for a pleasing variety. The collection grows every time we find something in an old book or catalogue that would make a suitable background.

The resources for building a collection are readily available. Old books at the Internet Archive commonly have marbled endpapers. Catalogues from tile and wallpaper manufacturers are full of patterns.

And, by the way, none of the patterns on this page are in Dr. Boli’s collection yet. It will take a while longer to exhaust the inexhaustible riches of the Internet Archive.

It takes a little practice to crop one of these patterns so that it repeats correctly—perhaps five minutes or so of practice.

Marbled endpapers, of course, cannot be tiled so neatly, but the complex ones are random enough that the seams are not offensive. In that sense, the marble patterns do in fact come from a random generator—namely, the constantly swirling colors on which the paper was laid.

STEAMPUNK GRYPHON.

ARTIFICIAL INTELLIGENCE HAS CHANGED THE WAY WE THINK ABOUT PICTURES.

Yesterday we ran a picture feature that caused one of our frequent correspondents, who goes by the name Occasional Correspondent, to wonder whether it was produced by AI. It was not; it came from a movie magazine that was 110 years old. But, as our correspondent pointed out,

Suppose that, say, a year or two ago, someone sat down to say, “Chattie! Gin up an issue of Photoplay magazine. Make it from 1914. Include some of Wister’s The Virginian. Include at least one photograph of a dramatic, face-to-face confrontation between cowboys. Post it on the Internet, we’ll see who takes the bait.”

But that way lies madness. Or maybe sanity. Hard to tell.

Dr. Boli would say sanity. Artificial intelligence has done us a great favor, and it was one we never expected. Instead of creating a public ready to swallow any misinformation, AI has taught us all to doubt every picture we see. And that is a very good thing.

A few years ago, National Geographic caused a big stink by moving a pyramid. Someone thought a photograph of the pyramids at Giza was imperfectly composed, and solved the problem by using image-editing software to move one of the pyramids. The picture ran on the cover, where millions saw it, including some who knew how the pyramids were placed in real life. There was a hue, and probably even a cry.

In the next issue, the editors apologized for what they could see, in the cold light of canceled subscriptions, had been a lapse in judgment. They promised never to use image-manipulating software to create a false impression again.

In that same issue in which the apology ran was a picture of an enormous ice bridge under which tiny people could be seen. But the ice bridge was not enormous. It was simply close, and the people were far away. The photographer had used a very-wide-angle lens with almost unlimited depth of field to make an inches-high bow of ice appear to be an enormous bridge. Deceptive? No, because no image-editing software was involved. At least, that seems to have been the decision of the magazine editors. On the other hand, the ordinary reader who was deceived (and Dr. Boli was one of them until he read the surrounding text) might say that it is the deception that matters, not the means of deception. In this case, it was possible to produce a deceptive image with the camera alone, not even resorting to the GIMP or Photoshop.

That brings us back to our original observation. People have begun to tell each other that we can’t rely on pictures anymore, because they may be simply made up. Artificial intelligence has taught us that, but the fact is not new. At least since the discovery of the double exposure by the first photographer who was not perfectly careful and organized with his plates, it has been possible to make photographs that look convincing but depict things that never were. Intelligent people noted for their stories about an extremely rational detective (not to mention any names) took pictures of fairies seriously. Political campaigns have been won by pictures purporting to show people who had never met being perfectly chummy. Most people seem not to have been aware of the extent to which photographs have been manipulated since the dawn of photography, so most people went through their lives trusting that cameras were telling them the truth.

That people have begun to suspect the veracity of photographs now is due almost entirely to the arrival of artificial intelligence. We can thus say that AI has done us a great favor by revealing to all and sundry what was always true about photography. We do not trust the camera anymore. We never should have trusted it, but if our enlightenment comes late it is still a good thing that it comes at all.

ASK DR. BOLI.

Dear Dr. Boli: Every once in a while I hear people talk about the “seven arts.” But they never say which seven they mean. Can you provide a canonical list of the seven arts, or will I have to go to Reddit and take my chances? —Sincerely, M. R. Jackson, Chairman, National Endowment for the Arts.

Dear Madam: The canonical list of the seven arts is updated periodically by the competent authorities, so it is important to keep up to date, which you can easily do by paying a small annual subscription fee to Competent Authorities LLC. For example, the list promulgated in August of 1971 specified the seven arts as tie-dye, macramé, protest songs, macaroni painting, carpet bombing, free verse, and laugh tracks. If you mistook that for a current list, you would be accused of wallowing in nostalgia. Here is the most recent list of the seven arts as it was announced in April of this year:

Graffiti

AI prompting

Tattoo removal

Auto-Tune

Telephone scams

Article-spinning

Tragic backstories

WHAT THE ALCOA CORPORATE CENTER NEEDS.

Our friend Father Pitt published some pictures of the Alcoa Corporate Center on the North Shore in Pittsburgh. It is a striking building that makes a good advertisement for aluminum as a building material, but to Dr. Boli’s eyes it seemed to be missing something. It took a while to decide exactly what it needed, but at last it came to him in a flash.

This building needs appropriately scaled Lionel trains.

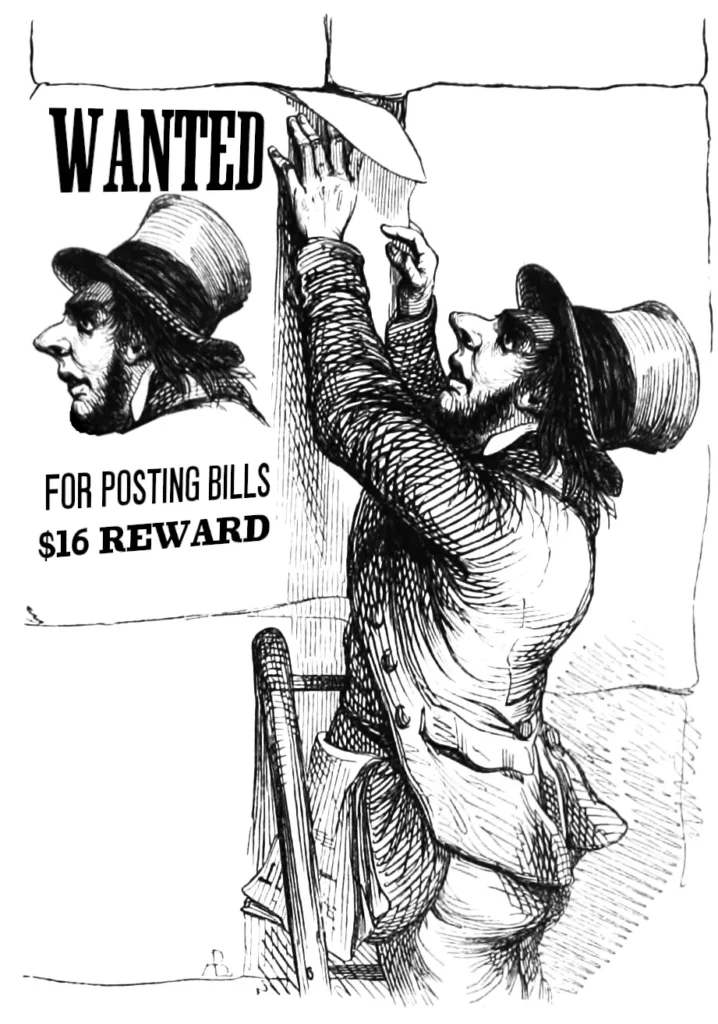

POSTING A BILL.

A DEPRESSION-ERA SUBURBAN TRAGEDY.

FROM THE ILLUSTRATED EDITION.

AN EARLY WORK OF FRANK GEHRY?

A TEMPLE OF OBJECTS.

An object.

As you leave the exhibit, you come to this sign, in which the museum apologizes for making you suffer through all that art. We duplicate it here for the purpose of comment and criticism.

Epilogue. As single-collector institutions, The Frick Pittsburgh and The Frick Collection are invariably linked to their individual founders. Both museums originate from a place of privilege, built on the backs of laborers in western Pennsylvania. Although genuine in the impetus to create something for the public good, many of the principles that guided the founding of our institutions no longer ring true. Today, museums strive to be centers of creativity, thought, and conversation, rather than temples of objects chosen by (and to represent) an elite few.

Here are a few essay questions on our assigned reading.

1. If museums are not to be temples of objects, then where should the objects be?

2. If the objects in museums are not to be chosen by an elite few—for example, by the vanishingly small number of intellectuals who have studied the history of art—then by what sort of democratic referendum are they to be chosen?

3. What will happen to the objects once we succeed in transforming our museums into centers of creativity, thought, and conversation? Will the objects go back into the hands of private collectors who will exclude the general public from viewing them?

4. If a museum is to be a center of creativity, thought, and conversation, how is it different from a coffeehouse? Is it just that the coffee is worse?

Dr. Boli will be very straightforward here. In his opinion, this is simple old-fashioned Yankee anti-intellectualism dressed up as fashionably enlightened righteousness. It is as silly to say that the “elite few” should not choose art as it is to say that a trained auto mechanic should not rebuild your transmission, or that a trained surgeon should not remove your appendix. What, you think I’m not good enough to perform an appendectomy? Just because I’m a cashier at the Circle K? I thought we were done with that kind of snobbery. It’s so nineteenth century.

It is also particularly antidemocratic anti-intellectualism, because of course the logical consequence of abandoning the idea of the museum as “a temple of objects” is that the δῆμος shall no longer have access to the objects. In the Frick Pittsburgh’s permanent collection you can see a colossal landscape by Boucher, and a portrait by Reynolds, and another by Gainsborough, and a whole room of early Italian Renaissance devotional art, and it’s free, because Helen Frick endowed the museum so that the public could always have free access to her art collection. The cleansing of the temple would mean that the art student who had taste but no money would no longer have that privilege.

What would our hypothetical impoverished art student see instead? Beside the “Epilogue” was a station with a table where visitors could think, exercise their creativity, and join the conversation by writing their thoughts on sticky notes and sticking them on the wall. This is what you should see in a museum, instead of stuffy old Rembrandt, who looks sad for some reason.

One of the questions you could choose to answer on sticky notes was “What would you like to see in a museum?” After thinking for a while, Dr. Boli picked up a pencil and wrote, “A temple of objects, chosen by an elite few.”

Portrait of a Man in a Red Hat, by Titian.