THE CRANK WHO HAS IT ALL FIGURED OUT.

There are various kinds of cranks, but what defines a crank for Dr. Boli is the subject’s firm belief that he has found some universal key that opens up vaults of knowledge locked away from the experts in the field. Only the crank has found the truth: that contagious diseases are spread by cell towers, or that the earth was created in 1958, or that Shakespeare’s plays were written by Beethoven, or whatever favorite hobby-horse our crank has mounted.

Why have the experts not found this key? Sometimes it’s a conspiracy: doctors, scientists, scholars all know this thing I’ve figured out, but they all lie to you, every one of them, because they’ve been paid off by tech companies or socialists or Big Shakespeare. But more often the crank falls back on the simpler explanation that the experts just aren’t very bright. He has explained his findings to them, patiently and exhaustively, but they turn a blind ear and a deaf eye. They dismiss him, ignore him, and even call him a crank. But they did the same to Galileo!

One common thread that runs through every province of crankdom is the confusion of science with philosophy. To be fair to the cranks, it is only lately—in the past two or three centuries—that science and philosophy have become two different things. What is the difference? Well, we might say that philosophy deals with the things that are too basic or too messy for science to deal with. For example, most of science depends on the law of non-contradiction: A and not-A cannot both be true at the same time. But science itself cannot prove the law of non-contradiction. It is too basic for science to deal with: it belongs to philosophy. Ethics are also important to most scientists, but they are too messy for science to deal with. You cannot design an experiment to prove that painful experiments on unwilling subjects are unethical. That does not mean that you cannot make a strong argument for that proposition, but it will be a philosophical argument. You will not be presenting data to show that a certain percentage of human beings object to being vivisected; you will be appealing to basic and deeply held beliefs about fair dealing and humanity. You will probably be very persuasive, but that is the difference. Science presents facts that, once understood, lead to a conclusion. The conclusion may be a probability, which is frustrating; but if the science is true science, then the degree of uncertainty is a certainty.

This brings us back to Christopher Booker, whose Seven Basic Plots, or at least three quarters of it, is a fascinating exercise in the philosophy of literature. But Mr. Booker believed he was doing science, not philosophy. He admits that many of “those critics and specialists in ‘literature’ who are already sure that they know what stories are about” will resist his conclusions. “But in the end,” he writes on page 700 of a 728-page book, “however inadequately I have argued the case, the general approach to stories set out in this book will come to be widely accepted, simply because it opens up our understanding of why we tell stories in a way which makes it scientifically comprehensible. However many examples the hypothesis is tested against, the laws hold.” The experts will resist me, but history will prove me right: this is the crank’s creed. He has discovered fundamental laws that “will hold.”

In Mr. Booker’s case, his laws will hold no matter how many stories we test them against because he has arranged his “laws” in a conveniently circular fashion: if a story, like Proust’s interminable novel or the plays of Samuel Beckett, does not fit one of his archetypal plots, then the story fails as a story and doesn’t count. No true Scotsman, etc. This is an oversimplification of his argument, but not much of an oversimplification.

Mr. Booker wanted to classify his endeavor as science because he craved the certainty of science. Just as Galileo’s laws of falling bodies came to be accepted by everyone who understands physics, so Booker’s laws of storytelling will come to be accepted by everyone who understands stories. And, of course, anyone who does not accept them does not understand stories, as our true Scotsmen might explain.

This was important to Mr. Booker because he had opinions that went beyond the world of literature. Having established his theory of storytelling as science, he could use it to prove that Margaret Thatcher was good and Tony Blair was bad. When we said that three quarters of the book was a fascinating exercise in the philosophy of literature, we had to except the last quarter of the book, which is sheer political crankiness, in which Mr. Booker applies his archetypal plots to recent history to show how they prove that Tories are right.

This is what happens when a crank devotes half his life to his pet hypothesis: he begins to think he has found the skeleton key to everything, that he has picked all the locks and opened up all the hidden mysteries of the universe. Homer and Shakespeare are not enough: his theory must explain all of human behavior. Perhaps it is a window into the very mind of God, and creation itself proceeded according to laws laid down by Christopher Booker.

This all comes of confusing philosophy with science. A scientist might be able to point out which parts of the brain are active when the mouth is telling a story, but why we tell stories is, for the present at least, a question both too basic and too messy for science. A philosopher may tackle it and produce some pretty arguments; but an honest philosopher (of whom there must be a few) would admit that those pretty arguments have not closed the debate. This is not to say that there are not uncertainties and debates and fistfights in science, but that is science in an intermediate stage. Science aims at the kind of certainty that philosophy can never reach. That is what makes the word “science” so attractive to cranks. To them it implies that the debate is closed: I am right and you are either convinced or a fool.

It is easy to dismiss cranks as not worth our time (unless they are entertainingly bonkers). But once in a while a crank, thinking he is doing science, produces some good philosophy. This is what happened with Mr. Booker. His analysis of how stories work is often persuasive, and his suggestions as to why we tell so many similar stories are at least interesting; how persuasive they are will depend on what you think of his idol Jung. Because he was a crank by nature, Mr. Booker could not resist extending his analysis to prove scientifically that Tony Blair was a puer aeternus, incapable of growth or resolution, and thus representative of the failure of Britain’s story after Thatcher. But ignore the crankiness—everything after the chapter heading “Into the Real World”—and there is much to admire.

Cranks do themselves no favors when they insist that their work is solid science. We are much more likely to accept unorthodox suggestions if they are offered as suggestions, with persuasive arguments that nevertheless admit that a reasonable reader could reach different conclusions.

But meanwhile, we reasonable readers can afford to be a little indulgent to the cranks. The ones who misunderstand the fundamentals can be dismissed at once—the flat-earthers, the astrologers, the peddlers of perpetual motion. But the ones who just confuse philosophy with science may have some interesting philosophy to show us.

FROM THE ILLUSTRATED EDITION.

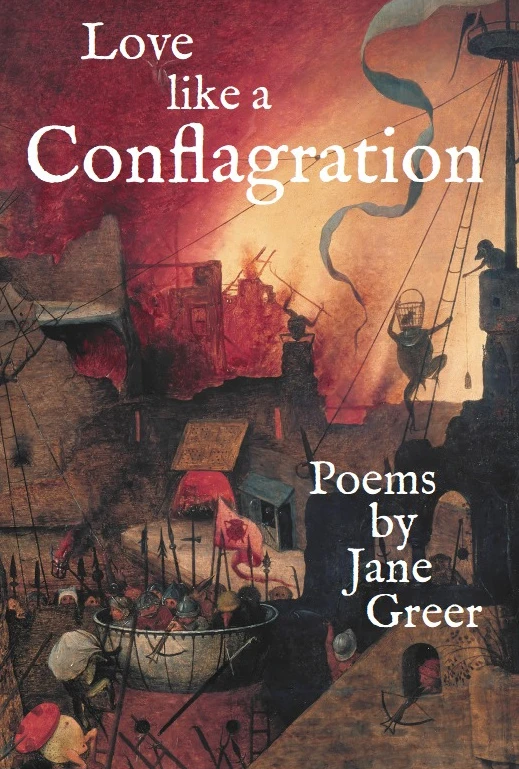

IN MEMORY OF JANE GREER.

We console ourselves for the loss by reminding ourselves that Jane’s poetry was only a small part of her work. She was a sower, and we are still reaping the harvest from the dozens of good poets she encouraged. She even encouraged your humble servant here, which shows us that charity was not the least of her virtues.

The loss to poetry is mitigated, then, by her enormous legacy. The personal loss is a little harder. Every so often we will run across something that we know would amuse Jane and no one else, and what can do with it?

The grief: I cannot seem to move beyond it,

but in this silence I will try to save

some shred of this beastly day, try to believe

in redemption, and that I am not the beast—

voice tight, teeth showing, my hour come round at last.

(From “Motherhood on the One Quiet Night” by Jane Greer.)

Two of Jane’s books are in print from Lambing Press. It was our honor to be present at the birth of both these books—not as the midwife, perhaps, but at least as one of those technicians who roll the cart in. If our own recommendation is not sufficient, they come with glowing recommendations from Samuel Hazo, James Matthew Wilson, Anthony Esolen, Ryan Wilson, Rachel Hadas, Boris Dralyuk, Maryann Corbett, and a host of other big names in current literature.

Advertisement.

FROM THE ILLUSTRATED EDITION.

Advertisement.

COMMUNITY BULLETIN BOARD.

FROM THE ILLUSTRATED EDITION.

A TIP FOR COPY EDITORS: QUESTION ETYMOLOGIES.

Some of your authors will understand the science of etymology. You will get to know those authors if you run across them. They are fabulously rare.

Others will take the trouble to look up etymologies in a dictionary. These authors are only slightly less rare.

Most writers who give you the derivation of a word are giving you an assertion they heard from a pedantic teacher in junior high school and never thought to question. Sometimes those etymologies may be right—generally when they are etymologies of complicated technical terms, which by their artificially constructed nature have very simple derivations. If your author tells you that hydrophilic comes from Greek words meaning water-loving, then her junior-high-school teacher was correct.

But these junior-high-school teachers usually go horribly wrong when they tell you the derivations of ordinary English words. And we can learn something about etymology just by seeing where they go horribly wrong. Here is Christopher Booker (whose fascinating brand of crankiness is exactly the sort of environment in which we are likely to find false etymologies) recalling what he must have learned in grammar school:

They [viz., ancient monumental structures] stood for that sense of “wholeness” which we derive from the Greek holos, which also gives us “holy” and “holiness.”

With admirable efficiency, Mr. Booker crams three false etymologies into one sentence. Wrong, wrong, and wrong. Dr. Boli could explain why the derivations are wrong, but anyone can look them up in the dictionary—Wiktionary is a good place to start. It does happen that “whole” and “holy” are related Germanic words (and both related to “health,” which would have given Mr. Booker much to think about if he had taken the trouble to open that dictionary), so the point could have been made without dragging in the unrelated though coincidentally similar Greek word.

But we see here one of the most common patterns in mistaken etymologies. Greek is ancient; English is modern; therefore any English term must have come from Greek, because Greek is older. The most superficial knowledge of history ought to be sufficient to dispel the notion that common, ordinary English words would have come from Greek: English is a Germanic language, and why would ancient Germanic tribes have imported their basic vocabulary from the Aegean? But your pedantic junior-high-school teacher never thought of that.

Another example comes a page later in the same book.

The Greek and Latin words for “god,” theos and deus, derive from the same Sanskrit root dyaus from which we get the word “day.”

Wrong, wrong, and wrong again. Surely Mr. Booker knows enough history that he does not seriously believe that speakers of Sanskrit, the highly developed literary language of India, moved west and became Greeks, Italians, and Cockneys. This is one Dr. Boli didn’t have to look up: it is a general principle that almost any derivation of a word in a European language from Sanskrit is wrong unless it refers to a specifically Indian phenomenon. Nevertheless, Dr. Boli did look up the words, because the dictionary is right in front of him, and it seems only fair to confirm his assertions before passing them on to the rest of the world as God’s own truth. Wiktionary informs us that, “despite its superficial similarity in form and meaning,” deus is “not related to Ancient Greek θεός.” The etymology of day is uncertain; at most it could be a distant cognate of the Sanskrit term, but, no, the Anglo-Saxons did not learn their word for “day” from the Indians.

These wrong etymologies are easy to catch, but no copy editor bothered to catch them. They came from Mr. Booker’s 2004 book The Seven Basic Plots, which Dr. Boli has been reading the past few days, and often wondering whether it went through a copy editor at all. Supposedly the author spent 34 years on the book, but few of those arduous years were spent in front of a dictionary or encyclopedia. And where was the copy editor? “Pharaoh” is a hard word to spell, perhaps, but a copy editor should know it’s a hard word and look it up, even if nothing about the spelling “Phaoroah” triggers alarms. The seven plagues of Egypt is giving Mr. “Phaoroah” an undeserved 30% discount. Dr. Boli is mystified how so obviously well-read a writer can write “thou cans’t,” as if it’s a contraction of some sort, every time he quotes “thou canst” from the Bible or Shakespeare—and even more mystified that a copy editor could let it pass. Mr. Booker himself clearly is quoting many of his sources from memory, and even when he gets the words right he often misremembers the context. Where was the copy editor?

It is interesting to note, therefore, that most of Mr. Booker’s later career was marked by his repeated insistence that he knew science better than all the world’s scientists, because he had sat and thought about it for a while, and presumably they had spent their lives playing badminton or watching soap operas and picked up their degrees at a rummage sale. Dr. Boli has not read any of those later attacks on science, but it would not surprise him to find that they were full of the same kind of thing: it must be true because it stands to reason, and I don’t have to look it up because I already know.

But that is a digression from the main point here, which is that, if you are a copy editor, you should assume that every etymology your author gives you is wrong, and look them all up. Wiktionary is a very good tool. The Oxford English Dictionary is unlikely to steer you wrong. If, after half a dozen etymologies, you find that your author has always been right so far, you may begin to relax your vigilance. But whenever a writer tells you where a word came from, your default assumption should be that the derivation is incorrect.