AN EPITAPH.

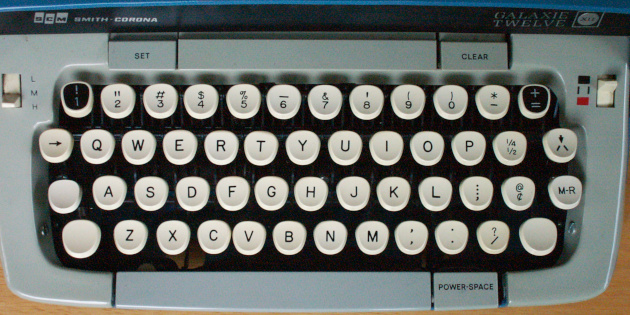

The typewriter is a Smith-Corona Electra 120, from a bygone era when it seemed like good marketing to name typewriters after characters in Sophocles.

INDOOR METEOROLOGY.

ON THE DEVELOPMENT OF A POETIC VOCABULARY.

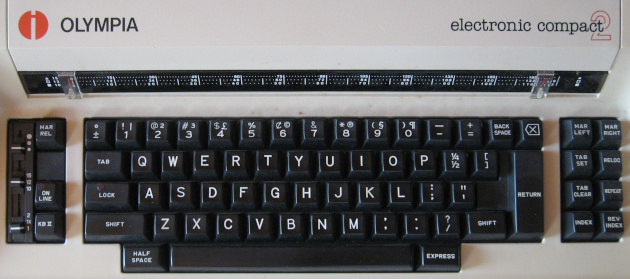

The typewriter is a 1984 Olympia Electronic Compact 2 with a Letter Gothic printwheel.

THE PRINTER’S APPRENTICE.

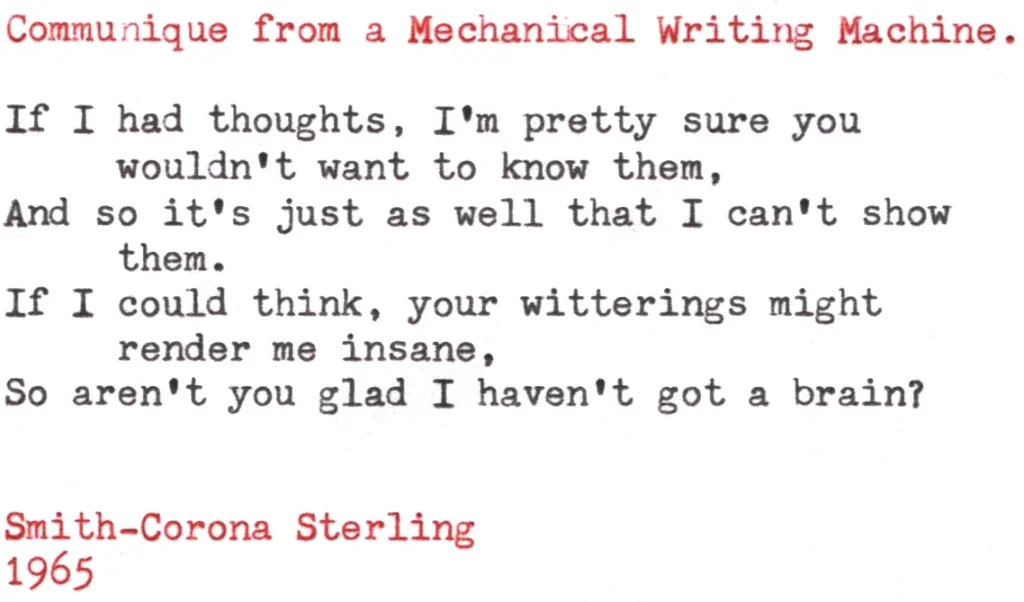

COMMUNIQUE FROM A MECHANICAL WRITING MACHINE.

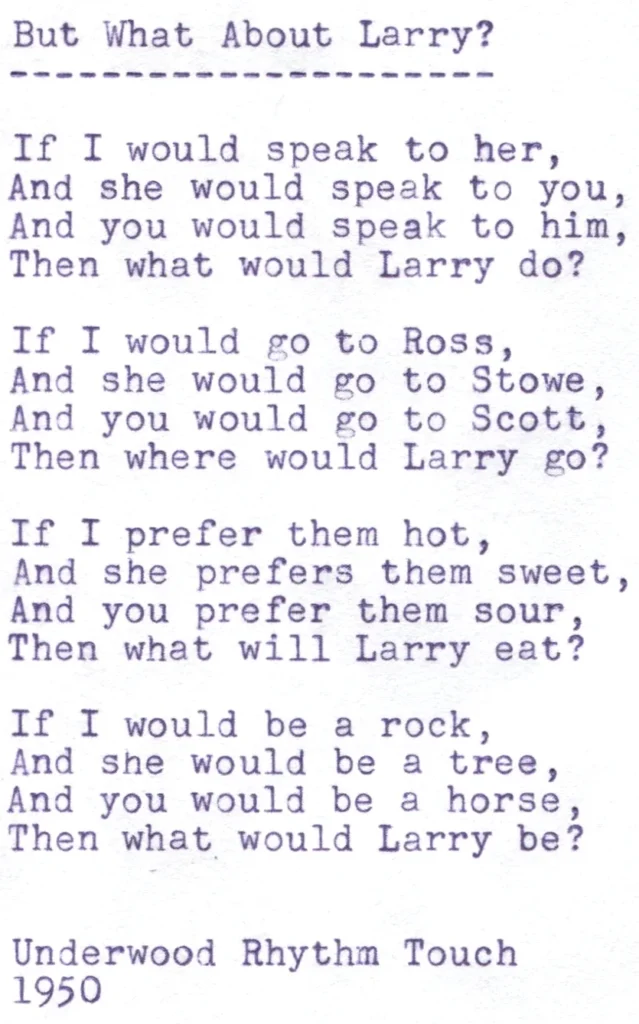

BUT WHAT ABOUT LARRY?

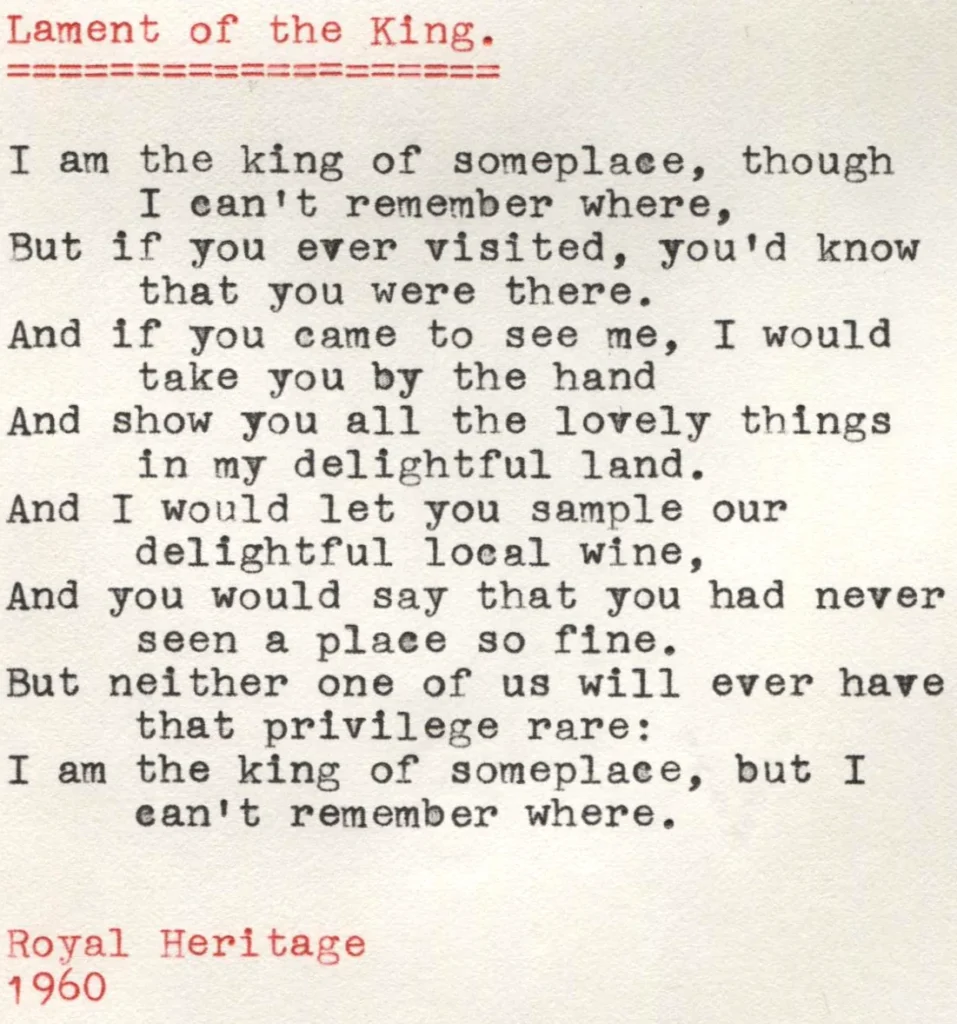

LAMENT OF THE KING.

ALCIPHRON.

The typewriter is a Swintec 1146 CM, made for Swintec by Nakajima in Japan.

And now, here is Dr. Boli’s preface for the new Serif Press edition of Alciphron, an attractively printed volume that can be ordered from Amazon for a reasonable price.

Alciphron is one of those classical writers of whom we must say that we know nothing, and whatever we know is probably wrong. Even his era has been the subject of intense debate, with opinions varying by centuries. The question was unsettled when the introduction to this Athenian Society edition of Alciphron was published in 1896, and it is still just as unsettled today. Therefore we shall not enter the debate.

Instead, we can ask what Alciphon’s work is and why anyone would want to read it. These are also unanswerable questions, but since they will remain unanswerable for eternity, we may safely debate them now.

Alciphron’s letters are a species of fiction, but it is difficult to fit them into any category of fiction modern readers are familiar with. That is surprising, because the letters strike us as extraordinarily modern. They turn our image of the classical world upside-down, lifting up the marble statues of heroes, kings, and emperors to show us the parasites, courtesans, criminals, and working stiffs scurrying like mad under the dignified stones above them. These characters are imagined as writing letters in good literary language, but expressing their hopes and motivations in just the way such people would feel them. The imaginary letters show us lower strata of Greek society filled with real people who have real thoughts, and we come away with the conviction that even a robber or a pirate is a human being just struggling to get through life.

Since the writing seems so modern to us, perhaps we might adopt a very modern term for it and call these letters flash fiction. Each one of them paints a vivid picture of one episode in the supposed writer’s life, but—like the best very short stories—these letters often suggest a much longer and more involved story in the background.

Now that we have a way of describing what the work is, we can move on to what it is for: that is, the vexed question of why we read fiction when we know it’s all lies.

The best answer to why we read fiction—at least good fiction—is that we learn more truth from it than we learn from any other source. We might read a scholar’s laborious study of the culture of parasites and courtesans in ancient Greece, coming away with a bundle of facts and statistics that would leak out of our brain like nickels from a pocket with holes in it. But Alciphron gives us a letter from a parasite who just had to endure a courtesan’s smacking him over the head with a bladder full of blood, while the rest of the dinner guests laughed themselves sick. We don’t forget that, and we know what it was like to be one of these professional comedians who traded all their dignity for a round of good dinners.

Although there is no agreement on when Alciphron lived, or even if the name “Alciphron” really belonged to the author, there is general agreement that he did not live in the times he described—the times when Epicurus and Menander were alive. Therefore these letters are, in a sense, historical fiction. They occasionally introduce real characters from history, like the comic playwright Menander—often considered Alciphron’s inspiration for his characterizations—and the philosophers who infested Athens at the same time. Thus in a sense Alciphron is imagining a world of which he did not have first-hand knowledge. But from our point of view he is still as reliable a purveyor of truth as a fiction writer—that is, an acknowledged peddler of falsehoods—can be. He did not live when Menander lived; but he lived in a world of parasites, courtesans, pirates, slaves, adultery, lawsuits, drunken dinner parties, and all the other characters and situations he describes so vividly. We live in a world of just as many evils, but they take different forms. Alciphron brings that dead world to life in our minds, and that is what his letters are good for.

The translation we have chosen comes from the Athenian Society edition of 1896, which was published privately and anonymously. It is reasonably accurate and pleasant to read. The original is an exceedingly rare book; only 255 copies were printed in total, with a solemn pledge never to print more. The Internet, however, changes our ideas of rarity, and more than one of those 255 copies can be found in online libraries. We take our text with gratitude from copy No. 35, preserved and scanned by the University of California. We have made no substantial changes to the well-printed text, correcting only a few obvious misprints. However, the 1896 edition had the Greek text on facing pages, which we have not printed here. We have also moved the notes from the back of the book to the foot of the page, so that readers will not have to turn to the back as many as three or four times in one page.

We should also mention that the names of the characters are meant to be indicative of their traits. The F. A. Wright translation of 1922 attempts to replace the Greek names with English equivalents and makes other adaptations to a modern English audience. Thus “Epiphillys to Amaracine” becomes “Kate Gleanings to Marjory Meek,” and her letter beginning “Having woven a garland of flowers, I was going to the temple of Hermaphroditus, intending to offer it in honour of him of Alopece,” instead begins, “I had made a wreath of flowers and was going to Alopekë where my Fred lies buried, to put it on his grave.” Fred from Alopekë was a bit much for us to take, so we left the names alone.

The arrangement of the letters has been left alone as well. The Loeb edition of Alciphron from 1949 has a table of seven different arrangements in seven different editions; the present arrangement into three books is not logical, but it is manageable.

The Letters of Alciphron at Amazon.

And now, for the benefit of screen-reader users and (of course) our robot friends, here is the transcription of the sonnet.

When all the rich are rotting in their graves;

When generals are mingled with the dust

Of privates, and the masters and the slaves

Have turned to dirt, as everybody must;

When swords and plows have crumbled into rust,

And no one struts, and no one pleads or begs;

When all the members of the upper crust

Are sunk down to the bottom with the dregs;

When crippled beggars earn their heavenly legs

And drink ambrosia like an honored guest;

When emperors are taken down six pegs

And buried with the poor and dispossessed;

Then Alciphron will still remember me,

And I shall have my immortality.

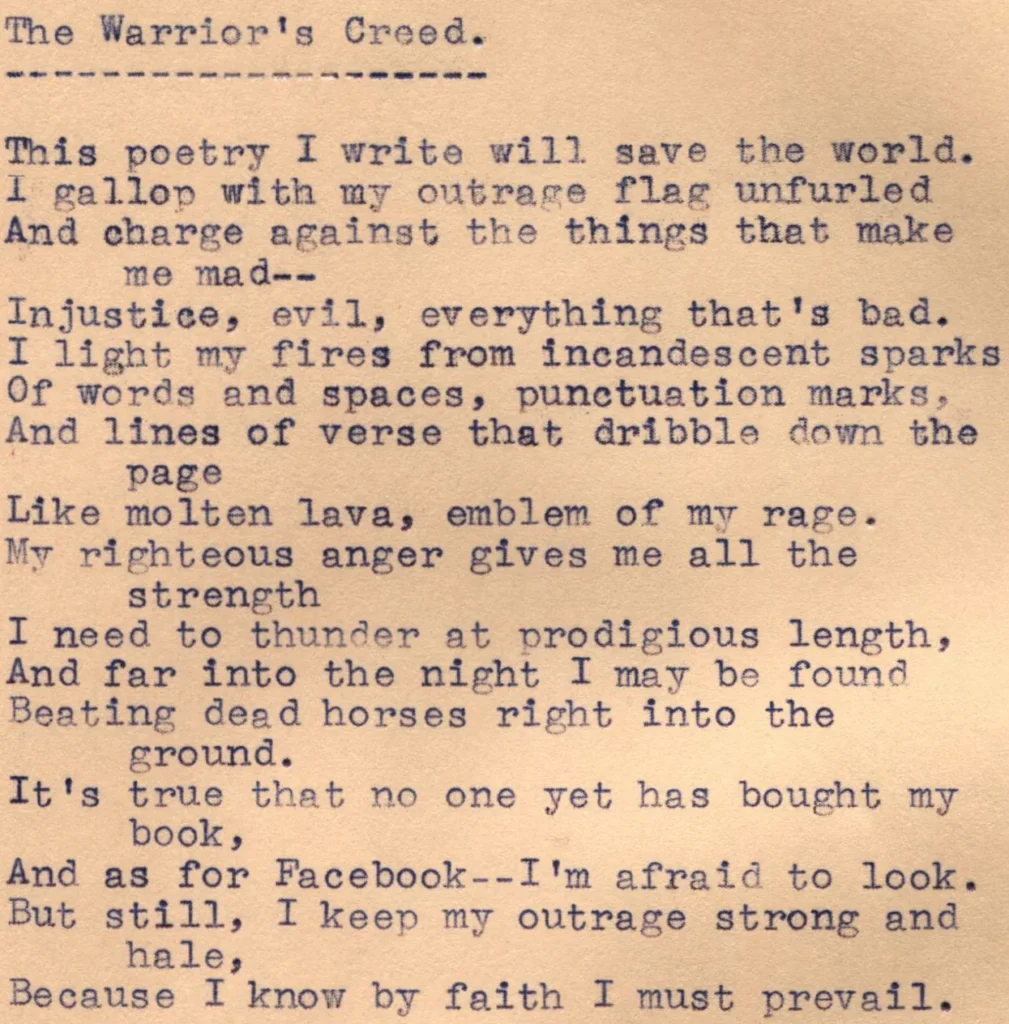

THE WARRIOR’S CREED.

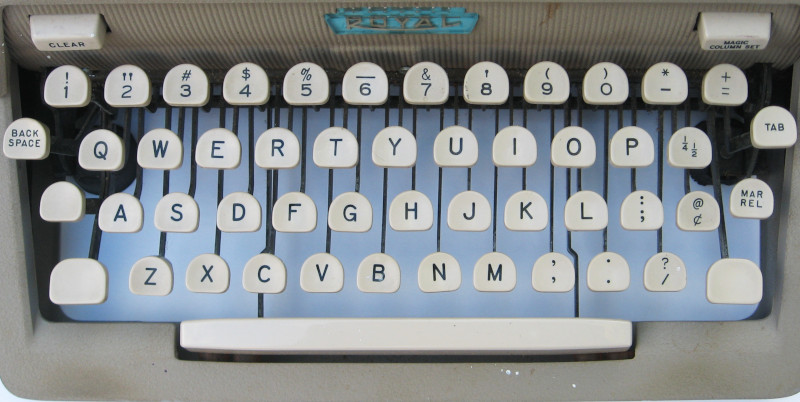

The typewriter is a 1948 Royal Quiet De Luxe, the Henry Dreyfuss “tuxedo” design.