IN HONOR OF the forthcoming third anniversary of his Celebrated Magazine on the World-Wide Web, Dr. Boli is reprinting some of the most notable articles, stories, poems, and advertisements of the past three years.

No. 412.—A National Monument.

HOW THRILLING IT was for Ned and me to see Mount Rushmore in person! The mountainous landscape, monumental in itself, and the green forest around the site gave a magnificence and color to the view that no photograph can adequately convey; and the colossal heads of four of our greatest presidents—George Washington, Thomas Jefferson, Abraham Lincoln, and Warren G. Harding, if I remember correctly—filled us with patriotic ardor. We talked of it all the way home from our vacation that summer, and we agreed that, impressive as it was, the monument at Mount Rushmore was deficient in one important detail: there was no memorial to William Howard Taft, surely our most monumental president. Our disappointment was tempered, however, by a happy notion that, as far as I could tell, occurred to both of us simultaneously. Why should we not correct the omission ourselves? We lived in a place that, by fortunate coincidence, was also blessed with many hills and rocky outcrops; and, as for the design, Ned had won second place in a school competition whose object was to sculpt a flattering portrait of the vice-principal out of salt dough. Moreover, the form of William Howard Taft was so mountainous in itself that half our work was done for us already, if we could but find a hill of suitable shape.

We soon settled on a rocky eminence overlooking the Youghiogheny. This hill already bore an almost eerie resemblance to President Taft; and it was moreover easily visible from our home below in the valley, so that we should have the privilege of admiring our handiwork every day from our own back yards.

Now we needed some method of turning this unformed mountain into an accurate portrait. From our preliminary research at the library, we were able to determine that it had taken many years and hundreds of workers for Mr. Borglum to form the gigantic portraits at Mount Rushmore. Ned and I had only a week until the end of summer vacation, so we were determined to find, if possible, a more expeditious method than the one adopted by that talented but inefficient sculptor.

It was I who, remembering the happy hours I had spent the previous year watching the construction of the Mid-Valley Connector, suggested explosives. By placing charges at exactly the right points in the rock, it should be possible to do all the work at once, shearing away those portions of the mountain that did not resemble President Taft and leaving only those portions that did.

But where to obtain these explosives in sufficient quantity? My father kept only a small stock of dynamite for medicinal purposes, and Ned could find none at all in his house.

Here, however, we had a bit of luck: for Ned recollected that there was an old abandoned coal mine just a short trip away by bicycle. We visited the site and found what we were looking for: the previous owners had left a stock of old dynamite in one of the chambers of the mine. It was a little unstable from sitting unused for so many years, but we carefully tied as much of it as we could to our bicycles and transported it to our mountain. It took several trips to bring as much as we needed, but finally we were ready to begin the excavations.

Ned had drawn a pencil portrait of President Taft on a sheet of graph paper, and now we carefully marked each edge and wrinkle for placement of the dynamite. We would need almost an entire bicycle-load just for the chins, and needless to say digging in all that dynamite was hard work. Sometimes we were a bit frustrated when we had carefully dug out a hole and found that the dynamite stick would not quite fit, and then we often had recourse to the sledgehammer—a practice that, when I look back on it, I can see was perhaps not as careful as it ought to have been. It actually took us three days to get all the sticks in place and wired to the detonator. But at last we were ready; and, by the flip of a coin, I was given the honor of pushing down the plunger to create our newest national monument.

The roar was deafening. We had expected a loud noise, but nothing had prepared us for the intensity of the explosion. An avalanche of rock ensued—far more than we had anticipated—and a huge cloud of dust rose and obscured our view for several minutes.

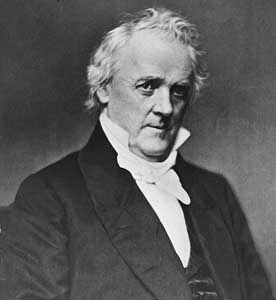

When the dust finally settled, we caught our first glimpse of the sculpture we had made. Just as we had intended, a colossal portrait now stood where the mountain had been before; but you can easily imagine our horror when we discovered that it was not a portrait of William Howard Taft at all, but rather of the traitor James Buchanan! The unstable dynamite had exploded with more force than we had calculated. The next day, as emergency crews worked to remove the rock and earth from the railroad and highway below, there was much speculation as to who could have created the masterful and artistic colossus that had mysteriously appeared above the river; but Ned and I were too much ashamed of our creation to take the credit for it.