Posts filed under “Art”

SMILE FOR THE CAMERA.

One of Dr. Boli’s frequent complaints about portraits today is that the subjects feel compelled to grin like imbeciles as soon as a camera is trained on them. “Smile for the camera” somehow became more than a tradition: it became a dogma. In fact younger readers may be surprised to learn that the phrase “Smile for the camera” was unknown before the middle of the twentieth century. It simply does not appear in literature. It was assumed that a portrait should show the subject in a dignified manner.

It is comforting, however, to realize that artificial expressions—and even the occasional feigned smile—have been the bane of portraitists for a long time. In 1623, John Webster’s play The Devil’s Law-Case was published, and Webster puts this speech into the mouth of one of his female characters. There is a layer of irony here, of course (as there often is in an English play of the classic period): the character who speaks these lines is herself vain and artificial. It should be noted that “is drawing” means “is being drawn”: in Webster’s time, the progressive form of the verb was not used in the passive.

With what a compell’d face a woman sits

While she is drawing! I have noted divers

Either to feign smiles, or suck in the lips

To have a little mouth; ruffle the cheeks

To have the dimples seen; and so disorder

The face with affectation, at next sitting

It has not been the same: I have known others

Have lost the entire fashion of their face,

In half-an-hour’s sitting.——John Webster, The Devil’s Law-Case, Act I.

IN ART NEWS.

Rejected by the Futurists for being too Cubist, by the Cubists for being too Symbolist, and by the Symbolists for being ugly.

The rejected preliminary sketch by Marcel Duchamp, Newt Descending a Staircase, has sold for £15.8 million at Sotheby’s, nearly a record for rejected preliminary sketches. The anonymous collector who sold the work reportedly bought it for five S&H Green Stamps, and so has made a comfortable profit.

THE PROFESSIONAL ARTIST.

A professional artist has a noble vocation. To beautify the products of commerce and industry, to ornament the living places of distinguished clients, to enliven public spaces with works that delight and instruct the passing crowds—these are worthy endeavors, and the artist who can accomplish them is worth a high price.

Such an artist must remember, however, that the client is the ultimate authority on what goes into her home, or her snack-food packaging, or her town square. The artist may have opinions, and the artist is free to express those opinions, and to reject the commission if he does not approve of the client’s decisions. That is the extent of the professional artist’s liberty. Like all workers, he has the freedom to choose whether he wants the money more or less than he wants to have everything his way. He is free to reject a job that does not appeal to him—or to decide that he needs to take it anyway because the bills are coming due.

There is a class of artists, however, who call themselves professionals, but insist that they alone have the right to dictate the content of their art. Their artistic vision must prevail, and they will not hear of interference from clients or committees. Most of them starve in garrets, but they starve proudly.

These artists have a perfect right to make their own decisions and face the consequences of them. When they call themselves professional artists, however, they are misusing the term. There is a word for this kind of artist, and it is amateur.

An amateur, as the etymology of the term implies, is someone who works for the love of the thing rather than for any financial remuneration. If you are uncompromisingly devoted to your art, and you refuse to be moved by money, then you are an amateur rather than a professional.

In most ways it is a nobler thing to be an amateur than it is to be a mere professional. A professional must always compromise; the amateur may have everything on his own terms. But the amateur cannot force me to pay for him to have everything on his own terms.

Now, it may happen that one’s artistic vision coincides precisely with what a certain segment of the public is willing to pay for in art. This seems to be what happened with Norman Rockwell, for example. Dr. Boli will make the unpopular admission that Norman Rockwell’s pictures always make him slightly queasy, but there seems to be no question that Mr. Rockwell loved what he did, and he certainly was well paid for it. In such a case there is no distinction between the professional and the amateur.

For some reason Americans tend to use “amateur” as a term of disparagement. Probably it comes from our tendency to assign a monetary value to everything. The highest compliment we can pay to anyone’s work is to call it professional, because the only way we know of measuring its worth is in money.

But money is not the measure of all things. It would be helpful to remember that the adjunct professor of philosophy at the community college is a professional teacher, but Jesus Christ was an amateur. Thomas Kinkade was a professional artist; Vincent Van Gogh was an amateur.

If you are making a living as an artist, you are a professional, and like all professionals you probably have to compromise your own taste every so often to give the client what she wants. You may have an infallible color sense, but if the marketer tells you those colors will not sell pretzels, then the marketer must have her way.

If, however, you refuse to compromise your principles, and you insist that your art must be taken your way or not at all, then you are doubtless a noble soul and deserve our commendation. But do not call yourself a professional artist. Call yourself what you are. Say the word: amateur. It will make you feel better.

FASHION TIPS.

INSPIRATIONAL POSTER

THE MIMEOGRAPH.

If you worked in an office where the mimeograph was treated in such a fashion, you might never get any work done, but you would doubtless rate your job satisfaction very highly. It seems to Dr. Boli that the standards in advertisements for office machinery have fallen considerably over the past century.

A NEW THEORY OF LATE-ANTIQUE ART.

Left: Portrait, probably of Arcadius, about 400 A.D., from Wikimedia Commons user Gryffindor (GNU Free Documentation License). Right: Anime image generated by StyleGAN, from Wikimedia Commons user ToaruRailgun (Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 4.0 International license).

If you look at Roman portraits from late antiquity, you will be struck by one singular characteristic. The eyes are enormous.

Theodosius the Great, from the Classical Numismatic Group, Inc., http://www.cngcoins.com, GNU Free Documentation License.

You may have noticed a similar phenomenon in Japanese cartoons, and in the American cartoons that imitate Japanese cartoons. It is Dr. Boli’s contention (which he offers to start a discussion in the art world) that these two stylistic phenomena are related.

Head of Constantine, photographed by Jean-Christophe BENOIST (GNU Free Documentation License).

These large eyes, then and now, are meant to sacrifice realism to expressiveness: they make the characters more human to the viewer. In a statue of an emperor designed to be seen from some distance, they allow the viewer to make a personal connection with the image that would not otherwise be possible. In a drawing meant to be hastily executed and printed on cheap paper, they have the same use.

Dr. Boli will put himself outside the limits of current art criticism by saying that they are also a substitute for talent. A really good artist makes the face expressive with the features at natural sizes. An artist without that talent magnifies the expressive features.

Clearly, however, once the big eyes were accepted as a technique, they became a style, adopted by the best artists as well as the mediocre ones. (We make the reasonable assumption that emperors would have their portraits done by the best artists, because there was no more honorable commission to be had.)

Dr. Boli does not know how important this observation may be to art historians or cartoon fans; but the connection between late-antique art and Japanese cartoons, if it has been made before, is at least not widely discussed. Once you have made the connection, though, you will probably find it very hard to unmake.

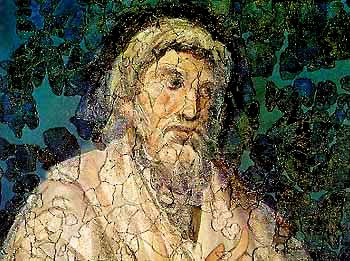

TWINS ACROSS TIME.

The illustration at the top of the Wikipedia article on Apuleius:

Late antique ceiling painting of Apuleius, c. 330

The illustration at the top of the Wikipedia article on Lactantius:

Mural likely depicting Lactantius.

Separated at birth—by about 125 years.

THE NATIONAL JUKEBOX.

Good news from the Library of Congress: the National Jukebox is back on line, now purged of Flash and ready for our brave new HTML5 world. Here, for example, is a recording of utter chaos by the Original Dixieland Jazz Band.

It may amuse listeners to note the “rights advisory”: “Inclusion of the recording in the National Jukebox, courtesy of Sony Music Entertainment.”

Dr. Boli cannot resist a quotation from the United States Constitution, which states that the Congress shall have power

…To promote the Progress of Science and useful Arts, by securing for limited Times to Authors and Inventors the exclusive Right to their respective Writings and Discoveries.

For the executives of Sony Music Entertainment, Dr. Boli has a question: How much of the profit (which is pure profit) from a 102-year-old recording goes to the author or inventor thereof?

We have only a little more than a year before this recording enters the public domain. We hope Nick LaRocca, Tony Sbarbaro, and the rest of the musicians will not suffer too much when they lose their constitutionally mandated revenues.