Posts filed under “Books & Literature”

From DR. BOLI’S UNABRIDGED DICTIONARY.

Argotnaut (noun).—A linguist who travels in search of obscure terms in slang or cant.

BANNED BOOKS.

To: Administrators, teachers, and librarians.

From: School Board of Grant Borough, Subcommittee on Moral Rectitude.

Herewith and hereunder please find a supplementary list of books to be added to the list of books heretofore banned from classrooms, libraries, and rest rooms in all three Grant Borough Public Schools, along with the reasons for banning each book.

The Tempest, by William Shakespeare. Banned for promoting magic and other works of the devil.

The Way We Live Now, by Anthony Trollope. Banned because it was, like, really long, so we had to assume there was obscene stuff in there somewhere.

Roget’s Thesaurus, by Peter Mark Roget. This is banned at the special request of Mrs. Wight, whose fifth-grade class has been looking into it and snickering for unknown reasons.

Canterbury Tales, by Geoffrey Chaucer. Sets an appalling example of bad spelling.

Tom Sawyer, by Mark Twain. Banned for promoting disruptive intelligence in young readers. Also because we have just found out that the author was a fraud: his real name was not Mark Twain at all!

The Scarlet Letter, by Nathaniel Hawthorne. Banned for setting an unreasonably high literary standard, which is discouraging to aspiring writers among our students.

Constitution of the United States, by Rutledge, Randolph, et al. We are tired of students mounting successful court challenges to school policies, and have detained the most recent round of complainers at an undisclosed location.

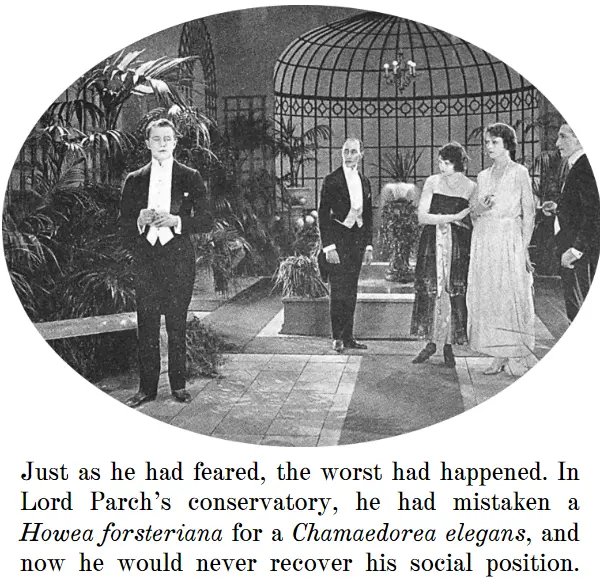

FROM THE ILLUSTRATED EDITION.

From DR. BOLI’S UNABRIDGED DICTIONARY.

Mystery (noun).—Any phenomenon or idea that human beings are still too stupid to understand.

THE LIFE AND GOOD WORKS OF MISS EVALINE BRACKET, M.L.S.

Scattered Notes for a Biography.

Miss Bracket made her début in society at the age of six, when she arrived for her first day in Mrs. Beardsley’s first-grade class in a chauffeured limousine, which was never seen again and caused some talk in the neighborhood, as the Haineses were not rich. On her first day of school, when the other children were at recess, Miss Bracket rearranged all the books she found in the classroom according to the Library of Congress cataloguing system. This would be her usual recreation for the rest of her school years. At first Mrs. Beardsley merely put the books back in their previous arrangement every afternoon once the children had gone home; but when the system according to which Miss Bracket had arranged the books was pointed out to her by the janitor (whose hobby was library science), Mrs. Beardsley began to experiment, bringing in more and more books on very obscure subjects. But no matter how arcane the disciplines, all the books would be arranged correctly by the end of recess.

Once, indeed, a debate arose between Miss Bracket and the janitor over the shelving of the Selecta capita philosophiae naturalis of Schellentragerus (Leipzig, 1723); but when the matter was referred to the Librarian of Congress himself, he gave his verdict in favor of Miss Bracket’s classification. The janitor’s mistake was attributable to his imperfect understanding of Latin. How Miss Bracket came to be fluent in the language at the age of six is not known.

Nor is it known how Miss Bracket acquired the prodigious strength she began to display in Mrs. Beardsley’s classroom. At first Mrs. Beardsley (according to her own testimony) supposed that the janitor was playing pranks on her; but then she walked into the classroom once during recess and found Miss Bracket carrying the big mahogany teacher’s desk to the other side of the room. When questioned, Miss Bracket explained that the furniture needed to be arranged in proper Library of Congress order.

For some time Mrs. Beardsley attempted to dissuade the child from her stated objective. She liked her desk where it was, she said, and it really was not necessary that the furniture should be arranged in some abstract pattern. Her efforts to reason with the child, however, had no effect: Miss Bracket had already reasoned for herself and come to a conclusion, and it was clear that, once a question was decided in her mind, no compromise, no deviation from what she knew to be correct, was possible. Mrs. Beardsley, like many others after her, learned to accept what her pupil had decreed, and by easy and almost insensible steps became one small part of a more perfectly ordered world. Soon the pupils in the class were themselves arranged according to the Library of Congress classification—for Miss Bracket had an almost preternatural ability to sense, and then to classify, the various personality types according to their essential nature.

Thus Mrs. Beardsley gradually adapted to Miss Bracket’s principles of organization, and even persuaded herself that the world was more to her liking when it was put in rational order; until one day in early March she drove herself to the school as usual and found that the school was not there. A small medical office building, inhabited by two neurologists, half a dozen gastroenterologists, and a color therapist, occupied the corner where the school had stood the day before.

It took quite a bit of driving here and there to find the school, which was three-quarters of a mile southeast of where it had been previously. In fact all the buildings on the boulevard, including a substantial shopping center, were in different places from the ones they had occupied the previous day. It would be difficult to describe the confusion that prevailed until at least noon. When at last Mrs. Beardsley did find the school, she was not amused to hear from Miss Bracket the reason for all the confusion. Miss Bracket had risen very early in the morning and rearranged the whole boulevard in proper Library of Congress order. She was a little tired, she said, but she would not allow fatigue to interfere with her schoolwork.

When the principal himself finally found the school, he called Mrs. Beardsley into his office, where she reluctantly agreed that a line had been crossed, and it would be necessary to call Miss Bracket’s parents in for a conference.

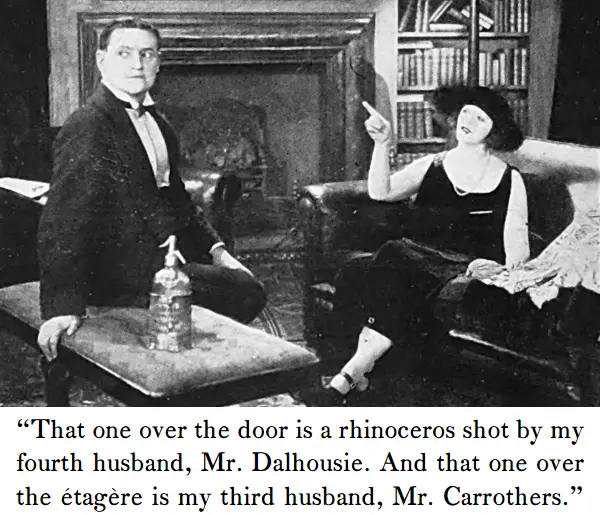

FROM THE ILLUSTRATED EDITION.

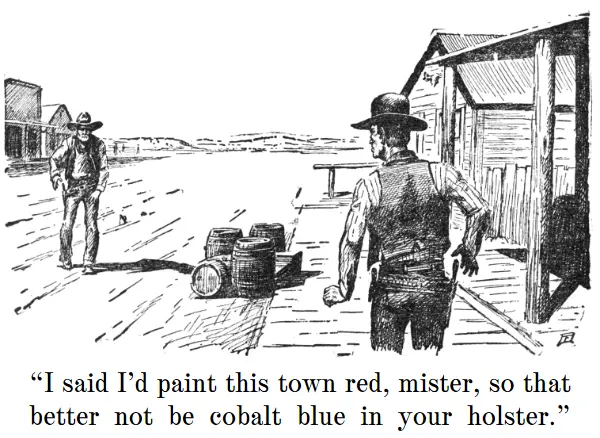

FROM THE ILLUSTRATED EDITION.

From DR. BOLI’S UNABRIDGED DICTIONARY.

Afflatus (noun).—The flatulence of a deity.

FROM THE ILLUSTRATED EDITION.

From DR. BOLI’S UNABRIDGED DICTIONARY.

Politics (noun).—Any organized method of deciding how many inoffensive bystanders must die in order to keep or gain power for a privileged class. (A disorganized method is called a riot.)