Posts filed under “History”

LET’S TALK ABOUT SOMETHING INTERESTING FOR A CHANGE.

This is not a new idea to you. You had already been aware of the water when you opened the book. It seems to you that the idea of “water” is contained in the idea of “ocean.”

But surely we must be about to get to the good stuff. You go on to chapter two and find that it describes in minute detail another class of evidence by which we can deduce that the ocean is full of water. The third chapter describes experiments with floating bodies, whose buoyancy proves that there is water in the ocean underneath them. The fourth chapter brings in a hygrometer, whose needle is pegged at the top of the scale when the end is dipped in the ocean. The rest of the chapters consist of stories of historical figures who went bathing in the ocean and came out wet. The concluding chapter summarizes all the evidence, and ends with a ringing declaration that it can no longer be denied that there is water in the ocean.

Well, that book was a disappointment. You didn’t learn anything about the ocean, because the book was only interested in the one thing about the ocean that you already knew.

So you take a class in oceanography at the community college—but once again you find that the professor and the course material have only one thing to tell you, which is that there is water in the ocean, and nobody can deny it.

In desperation, you turn to YouTube—a desperate measure indeed—and find that most of the videos that come up when you search for “ocean” are all about the astonishing and outrageous discovery that there is water in the ocean.

What would you think after all that? You would think that the whole intellectual world had managed to miss the point of oceans. You would think that everyone was belaboring the obvious. You would think that people were depriving themselves of the astonishment and delight they could enjoy if they only looked at the things in the water rather than at the water itself.

We are fortunate that we do not live in that intellectual world. But you probably guessed already (if you are the sort of reader who has the patience for five hundred words of introduction) that we were using the case of the ocean as an analogy for something else.

For most of human history, it was the nearly universal assumption that men and women are different and have different roles. There are still people who believe that today. Dr. Boli is not one of them, and he will explain why very briefly. The assumption was probably useful in paleolithic times, when the sexual dimorphism we inherited from our primate ancestors was a meaningful distinction. In those days it was good that there was one class of big strong oafs who went out to bonk mastodons on the head, and another class of more nimble and thoughtful members of the tribe who made plant fibers into thread and processed the mastodon skins and raised the young and coordinated the meals and established the rudiments of what would later become civilization.

But we might define civilization as the gradual process of making physical differences between human beings irrelevant. A woman can order from Grubhub as easily as a man can. A man can push buttons on the microwave as easily as a woman can. In a world where intellectual capacity is the most important ability, no physical difference between men and women is significant in deciding what position any individual should hold in life.

You may agree or disagree with Dr. Boli’s assertion, and for the purpose of our discussion here it makes no difference at all. We need only agree on the historical fact that, until quite recently, it was almost universally believed that men and women occupied different positions in society. In spite of occasional brilliant cranks who thought otherwise, there was no really serious challenge to that idea until the late eighteenth century at the very earliest.

So when academics look at literature from the past and find evidence of sexism, they are doing exactly what our hypothetical oceanographers did when they presented conclusive evidence that there is water in the ocean. They are telling us what everybody knows, over and over again, ad infinitum and ad nauseam. They are pointing out the water in the ocean.

Yet they do it over and over. Whole academic careers are built on analyzing the literature of the past in terms of patriarchy and the subjugation of women, which is exactly analogous to analyzing the ocean in terms of water. That was the environment in which the people of the past lived. We know that. But there were whales, and angelfish, and sharks, and sea otters, and giant squid, and glorious coral reefs filled with unimaginably colorful life. Wouldn’t it be more fun to talk about those?

Dr. Boli has a proposal for academic literary critics—or art critics, or any other students of the culture of the past. He will stipulate, as they say in the legal business, that the history of the past is a record of the subjugation of women by men. He will even stipulate that the past would probably be improved if we went back and kicked most of those men out of their leadership positions and stuck random women in there instead. The women could hardly do worse. In return, because he has made those stipulations, you do not need to argue your case anymore. Your assertions are admitted. They will not be challenged. Instead, you can start to look at the marvelous things the people who lived in the past did with the world they were given. If you do that, Dr. Boli will probably buy your books.

From DR. BOLI’S ENCYCLOPEDIA OF MISINFORMATION.

Yankee Doodle.—Because the facts of the case did not fit the meter or rhyme scheme, the musical biography of Yankee Doodle leaves out the important information that, on the same occasion when he stuck a feather in his cap and called it Macaroni, he also stuck a carnation in his lapel and called it Cheese.

ON THIS DAY IN HISTORY.

IS HISTORY IMPOSSIBLE?

But if you are still here, you probably noticed that the question in the title is provocative, and perhaps even despairing. Is it possible to write an accurate account of things that happened in the past, or is anything before our own lifetime so far gone from us that we can never understand it?

Dr. Boli is not a pessimist; he believes that good history can be written. But he also believes that it seldom is written, and that there is an unrecognized intellectual assumption current in our own time—an assumption we share with medieval historians—that prevents all but the best historians from writing any history worth reading.

These musings come from a question that Dr. Boli wanted to answer for himself. Is there a complete list of Isham Jones’ songs anywhere? Isham Jones, for the younger people, which is everyone who is not Dr. Boli, was one of the popular songwriters of the 1920s and into the 1930s. You may not know his name, but you have heard “It Had to Be You,” so you know Isham Jones. He had a distinctive way of constructing a melody, of which “It Had to Be You” is a fair specimen: take one short musical phrase, repeat it, transpose it, turn it upside-down and inside-out, and you have a song.

Uniquely among the top songwriters of the 1920s, Isham Jones was also a bandleader. He led his orchestra until the middle 1930s, when he decided to retire and live on the royalties from his songs. The orchestra continued under his young singer and reed player Woody Herman, and some of the young folks may be old enough to remember Woody Herman’s band, which was still playing into the 1980s.

All this is preface to explain what Dr. Boli was looking for when he landed on this ad-laden page at “SecondHand Songs,” a site devoted to sorting out cover versions from the original songs. And the fact that Isham Jones appears in this site at all shows a complete misunderstanding of the music business in the 1920s. But it is a misunderstanding that is so universal that there seems to be no correcting it. The truth is so far beyond the imagination of current music lovers that the past must be altered to conform to the norms of the present.

In the twenty-first century, a “song” is associated with a particular performer. If Beyoncé releases a recording, that song was probably written for her in particular. If it was not—if it was written for a different performer—then Beyoncé’s recording is a “cover version,” defined by Wikipedia as “a new performance or recording by a musician other than the original performer or composer of the song.”

Of course this definition makes the unexamined assumption that there is an “original” performer of a song.

That was not true in the 1920s. Song-publishing was a big business, and song publishers expected to make most of their money from sheet-music sales. So a song was written for everybody. It was not written for one particular performer any more than a novel was written for one particular reader. The sheet music was scored for piano accompaniment, because just about everybody had access to a piano, but usually it also had ukulele or guitar chords.

When a song was published, if it was by a well-known songwriter like Isham Jones, every big and small musical group across the country would be expected to play it. Remember that recordings were not the main way music was consumed, even though records were a big business: it was actually true that, if you walked into a large restaurant, there would be live musicians right there, in the restaurant, playing the latest songs. Dancing was big business. Nightclubs were everywhere. Speakeasies had small jazz bands.

As for recordings, the same principle applied. Every record company would record the new song. Often there would be more than one recording from the same company. A famous singer might record a vocal version with only piano accompaniment, or with a small group. Then a dance band might be brought in to record an instrumental dance version of the song, or a dance version with one chorus of vocal. If it was a record company that had a line of “race records,” a Black jazz band might be brought in to record the song for that market.

Now, which of these records is the “original” and which the “covers”? Obviously those categories do not apply. They assume a completely different business model.

So, with that introduction, go back to the Isham Jones page at “SecondHand Songs” and admire the amount of painstaking research that went into determining which was the “original” version of each song and which were the “covers.” Dr. Boli does not know what criteria were used to make these determinations—only that, whatever the criteria, the determinations are wrong, because the categories do not apply to the songs in question.

But the misunderstanding is universal, and it is part of a complex of misunderstandings that show the conditions of a later era being projected back on the 1920s. Look at the Wikipedia article on Isham Jones. In the list of compositions by Jones, we see several noted as “number 2 single for year 1925,” and so on. Whose version was the popular one? And what does “single” mean? In 1925, a confused record-company executive would probably have told you that it was a double, not a single, because there was another recording on the other side. (Some high-class records, like some of Caruso’s, really were single: they were released with only one side, the other being completely blank.) “Single” became a meaningful distinction only when the LP record came on the market, which was in 1948.

The Wikipedia article on “cover version” is even more dismaying, because it shows the work of someone who has put a great deal of effort and thought into sorting out the history of cover versions, but has unknowingly brought all the assumptions of his own era with him into the past. (You will note that the article carries the “needs additional citations” template, because for paragraphs at a time there are no citations at all.)

Early in the 20th century it became common for phonograph record labels to have singers or musicians “cover” a commercially successful “hit” tune by recording a version for their own label in hopes of cashing in on the tune’s success. For example, Ain’t She Sweet was popularized in 1927 by Eddie Cantor (on stage) and by Ben Bernie and Gene Austin (on record), was repopularized through popular recordings by Mr. Goon Bones & Mr. Ford and Pearl Bailey in 1949, and later still revived as 33 1/3 and 45 RPM records by the Beatles in 1964.

Because little promotion or advertising was done in the early days of record production, other than at the local music hall or music store, the average buyer purchasing a new record usually asked for the tune, not the artist. Record distribution was highly localized, so a locally popular artist could quickly record a version of a hit song from another area and reach an audience before the version by the artist(s) who first introduced the tune, and highly competitive record companies were quick to take advantage of this.

This is almost all unsourced, almost certainly because it comes from the writer’s own observations of the music of the past, and his own deep cogitation and consideration of the causes of the phenomena he observed. But he did his research mostly among records. If he had looked in old magazines, for example, he would not have written that “little promotion or advertising was done in the early days of record production.”

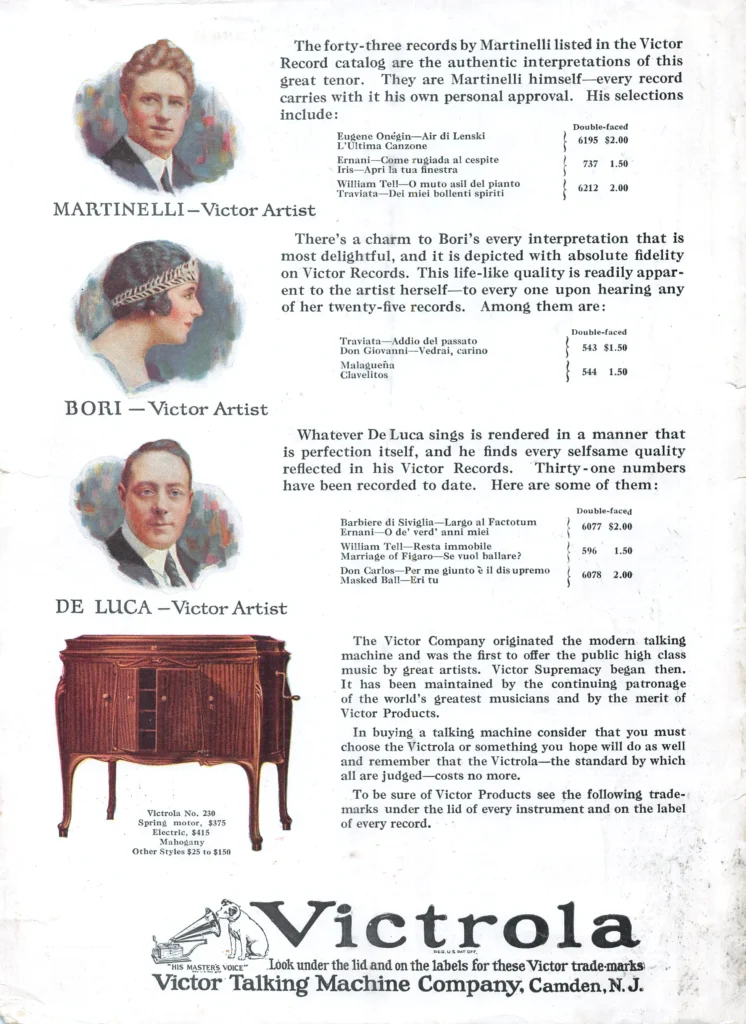

This advertisement was the entire back page of Popular Science for November, 1923—the most expensive ad in the magazine.

It reminds Dr. Boli of medieval historians, who unconsciously imagined the ancient world as a feudal society full of medieval lords and knights, because they could not imagine a world that was organized on any other principle.

And can any historian do better than that? Can any historian do more than observe the phenomena of the past, and then try to figure out what caused them to be the way they were?

Well, yes. You can do more. You can live in the past. Now, Dr. Boli admits that he has a certain advantage here, but his advantage disappears when we speak of the more remote past. There he is in the same boat as all the other historians. But he does not mean that only old people can write history. What he does mean is that a historian should spend a long time immersed in the details of the past.

For example, a writer trying to write a history of music in the 1920s must realize that recordings are only a tiny bit of the history. Popular magazines, newspaper advertisements, novels, and movies will give us a broader picture. You see the scenes in the movies of people dancing in restaurants, and realize that people used to do that—and therefore there must have been music. You read the scene in the novel where the heroine picks up a song and sits down at the piano to play it, and realize that, to her, “a song” meant something printed on paper. You see the ads in magazines from song publishers and see that their songs were available in arrangements for popular orchestra, and realize that every musical agglomeration across the country could buy that song and play it, as thousands must have done or the ads would not have paid. You read the debates in music magazines over whether those “stock arrangements” are adequate for a high-class band, or whether a really good orchestra should have its own arranger to do “specials.” If your eyes are open and your brain swept free of assumptions, you begin to get a picture of how those unaccountable people of the past actually lived.

That is what Dr. Boli means by living in the past. Before you set finger to keyboard, you must spend some time wallowing in the original sources. Not only the great figures of the time: they certainly are important, but they are by definition outliers, women and men whose minds went beyond the temporary assumptions of their era. Immerse yourself in the ordinary. Pile up heaps of ephemera. Live the intellectual life that the ordinary citizens of the past lived, and you will begin to understand the world they lived in.

And then you can come back to our own world and rewrite the Wikipedia article on “cover version.”

ENSLAVED PERSONS—OR SLAVES?

“Slavery,” by Fritz Erler, from Deutsche Kunst und Dekoration

I’ve always been annoyed when modern historians use the term “enslaved persons” to describe slaves. I know their intention is to imply that slavery is imposed rather than innate, but it strikes me as somehow disingenuous.

The phrase “enslaved persons” has always made Dr. Boli a little queasy, too. But why is using the term “enslaved persons” so objectionable?

First, because it deprives us of a useful distinction. A person who has been enslaved has gone from a state of not-slavery to a state of slavery. (We avoid the term “freedom” here so as not to provoke an endless debate with the Calvinists over what “freedom” means and whether anyone has it.) The verb “enslave” has precisely that meaning: to make a slave of someone who previously was not a slave. In the eventful record of human history, which is a catalogue of the crimes committed by humans against humans, it is necessary over and over to mark this passage from not-slavery to slavery in individuals and in whole populations. We need a word for it, and we had a perfectly good one.

But that is not what makes Dr. Boli cringe when he hears the term “enslaved persons” when what is meant is “slaves.” So what is it, then? Is it just the multiplication of syllables—four syllables where one would do the job better? No; Dr. Boli himself (you may have noticed) is sometimes willing to multiply syllables when the multiplication serves his purposes. The grating thing is the implication that, by inventing a new term, we have made it all better. We have restored human dignity to the generations of people who groaned under the yoke of slavery.

No, we haven’t. They were slaves. Millions of them were born slaves, lived slaves, and died slaves. They were human beings with all the natural rights that human beings inherit, and all the power of a civilized nation was marshaled to make sure they exercised none of those rights. That happened, and nothing we do can make it all better for them; our only consolation is the near certainty that they are now in a better condition than many of their former masters. We have a duty to come to terms with the fact that some very bad things have happened in history, and we can’t go back and kiss them better with a word. The only thing we can do is insist that those things will never happen again.

That is the thing we neglect, precisely because, when we say “enslaved persons” rather than “slaves,” it makes us feel as though we have already exercised all the virtue in the world, and there is nothing left to do. No—we have done nothing for anybody by saying “enslaved persons.” We have only rubbed a little ointment on our itchy conscience, without asking ourselves why we have that itch. Is it there because some little voice in the back of our minds is saying something we don’t want to hear? Do we hope to silence the voice by substituting “enslaved persons” for “slaves”? Then perhaps it is time for us to recognize that silencing the voice of conscience is exactly what has allowed slavery to fester over and over again throughout history. Perhaps we ought to listen to the voice instead of trying to shut it up by burying it under mounds of soothing syllables. Perhaps it has a message we need to hear. It might, for example, be trying to tell us, “You’re doing it again.”

DADDY, WHAT’S THAT?

Q. Why does the house have a pointy cone with a spike on the corner?

A. To discourage rubber-suited monsters from stepping on it. If a Japanese rubber-suited monster comes stomping through your neighborhood, it will see the spike on your house and flatten your neighbor’s house instead.

Q. Why are there so many different patterns in the woodwork?

A. Because the last thing you want at a construction site is a bored carpenter.

Q. Our house only has two floors. This one has three. What’s the third floor for?

A. In Victorian times, it was fashionable for better families to have mad great-aunts, who were installed in their own rooms on the third floor to keep them away from the matches in the kitchen.

Q. What’s that weird metal tree growing out of the chimney?

A. This is the hardest question to answer in a way that you young people can understand. Let us say that it was a primitive receiver for streaming media.

THE CHAPELS ON THE ROOF.

Near the center of the photo is an extremely bright white thing—seems to have spires—a church? That’s an impressively bright white. Is it actually as bright as appears? Did the photographer have to take a longer exposure to get the other buildings’ colors to show up?

Yes, it is very bright. We borrowed the photograph from our friend Father Pitt, who explains that the floodlit structure is so brightly lit that it would take a stack of different exposures, sandwiched together with computer wizardry, to capture the detail in the white object and the rest of the buildings at the same time, and he was too lazy to do that.

But what is the bright white thing? The picture above will show you what it looks like, but to understand its place in both history and legend, we have to go back to Henry Clay Frick.

The floodlit structures are not actually on the ground. They are—as our correspondent “von Hindenburg” pointed out—on the roof of the Union Trust Building, which is an extraordinarily ornate block-long building in the Flemish Gothic style.

The picture above, again from Father Pitt, is a composite, and the automatic stitching software left some amusing relics.

Our story really begins, though, with a building that no longer exists. Chicago, New York, and Pittsburgh were the three original homes of the skyscraper, and Pittsburgh’s first skyscraper was the Carnegie Building. Imagine the impressive and even terrifying effect of the first skyscrapers going up when no one had ever seen such a thing before:

From an advertisement in J. M. Kelly’s Handbook of Greater Pittsburg, 1895.

No matter where you were in downtown Pittsburgh, you could see this thing, and you would think the name “Carnegie” in your head.

Henry Clay Frick had been Carnegie’s friend and trusted associate, but the two men had a falling-out after the labor war in Homestead. So Frick threw what could only be described as an architectural tantrum. You may put a Freudian interpretation on it if you like. Frick bought the lot next to the Carnegie Building, paying the St. Peter’s Episcopal congregation enough to have their church moved stone by stone to the Oakland section of Pittsburgh. Then he hired Daniel Burnham to design a skyscraper that would be much taller than Carnegie’s, so that tenants on that side of the Carnegie Building would see nothing but the wall of the Frick Building out their windows. Then Frick bought the lot on the south side of the Carnegie Building and had Burnham design the Frick Annex (now the Allegheny Building), another taller skyscraper that blocked in the Carnegie Building on that side.

Across narrow Fifth Avenue from the Carnegie Building was St. Paul’s Cathedral. Frick made the Catholic Diocese of Pittsburgh an offer it couldn’t refuse, and then he tore down the cathedral to replace it with the most magnificent shopping arcade in the United States—blocking in the northern face of the Carnegie Building. Ultimately the Carnegie Building became a stuffy and claustrophobic place, and in the 1950s it was finally torn down and replaced with the nearly windowless Kaufmann’s Annex.

This arcade, the Union Trust Building, was designed in the office of Frederick Osterling, who usually gets credit for it, although it appears that the actual design was by Pierre Liesch, who worked for Osterling. Frick and Osterling had a falling-out, too, and Frick decided to ruin Osterling, whose major commissions downtown dried up. (On the other hand, when Osterling died years later in the middle of the Depression, he left an estate worth a million and a half, so he probably didn’t need the work.) But the building remains, and it generated legends.

From street level you can just make out these odd constructions on the roof.

What are they? Where there is an urban phenomenon, there is an urban legend to explain it. Pittsburghers remembered that Frick had torn down a cathedral to put up this building. The story is still told today that the Catholics had extorted an agreement from Frick: he could have the lot only if he included a chapel somewhere in his building, where he could retreat to repent privately of his many sins. If you look up, Pittsburghers say, you can see the chapels where Frick did his repenting.

This legend is a tribute to the constitutional charity of Pittsburghers, who are so charitable that they can imagine even Henry Clay Frick repenting.

But as our friend Father Pitt wrote sixteen years ago, “The truth is more prosaic and yet more impressive as an architectural accomplishment: the chapel-like structure houses the mechanics for the elevators and other necessities that normally make ugly blisters on the roofs of large buildings.”

Nevertheless, the “chapels” are such a distinctive feature of the building that the current owners have floodlit them. They are the brightest object in downtown Pittsburgh at night, and the bright lighting only feeds the legends.

ON THIS DAY IN HISTORY.

BASTILLE DAY.

A house in Pittsburgh flies the French flag.

From DR. BOLI’S ENCYCLOPEDIA OF MISINFORMATION.

Bald Eagle.—In spite of their ultrapatriotic reputation, three out of five American Bald Eagles voted for Eugene Debs in the 1920 presidential election.