DADDY, WHAT’S THAT?

Q. Why does the house have a pointy cone with a spike on the corner?

A. To discourage rubber-suited monsters from stepping on it. If a Japanese rubber-suited monster comes stomping through your neighborhood, it will see the spike on your house and flatten your neighbor’s house instead.

Q. Why are there so many different patterns in the woodwork?

A. Because the last thing you want at a construction site is a bored carpenter.

Q. Our house only has two floors. This one has three. What’s the third floor for?

A. In Victorian times, it was fashionable for better families to have mad great-aunts, who were installed in their own rooms on the third floor to keep them away from the matches in the kitchen.

Q. What’s that weird metal tree growing out of the chimney?

A. This is the hardest question to answer in a way that you young people can understand. Let us say that it was a primitive receiver for streaming media.

Advertisement.

FROM THE ILLUSTRATED EDITION.

BUMPER STICKER.

THE CHAPELS ON THE ROOF.

Near the center of the photo is an extremely bright white thing—seems to have spires—a church? That’s an impressively bright white. Is it actually as bright as appears? Did the photographer have to take a longer exposure to get the other buildings’ colors to show up?

Yes, it is very bright. We borrowed the photograph from our friend Father Pitt, who explains that the floodlit structure is so brightly lit that it would take a stack of different exposures, sandwiched together with computer wizardry, to capture the detail in the white object and the rest of the buildings at the same time, and he was too lazy to do that.

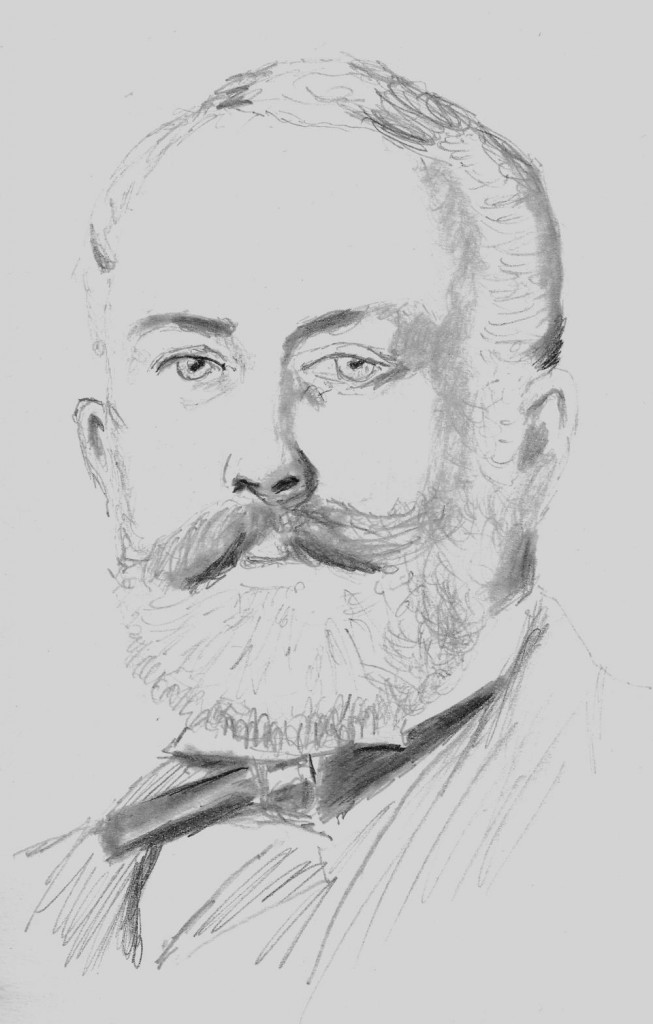

But what is the bright white thing? The picture above will show you what it looks like, but to understand its place in both history and legend, we have to go back to Henry Clay Frick.

The floodlit structures are not actually on the ground. They are—as our correspondent “von Hindenburg” pointed out—on the roof of the Union Trust Building, which is an extraordinarily ornate block-long building in the Flemish Gothic style.

The picture above, again from Father Pitt, is a composite, and the automatic stitching software left some amusing relics.

Our story really begins, though, with a building that no longer exists. Chicago, New York, and Pittsburgh were the three original homes of the skyscraper, and Pittsburgh’s first skyscraper was the Carnegie Building. Imagine the impressive and even terrifying effect of the first skyscrapers going up when no one had ever seen such a thing before:

From an advertisement in J. M. Kelly’s Handbook of Greater Pittsburg, 1895.

No matter where you were in downtown Pittsburgh, you could see this thing, and you would think the name “Carnegie” in your head.

Henry Clay Frick had been Carnegie’s friend and trusted associate, but the two men had a falling-out after the labor war in Homestead. So Frick threw what could only be described as an architectural tantrum. You may put a Freudian interpretation on it if you like. Frick bought the lot next to the Carnegie Building, paying the St. Peter’s Episcopal congregation enough to have their church moved stone by stone to the Oakland section of Pittsburgh. Then he hired Daniel Burnham to design a skyscraper that would be much taller than Carnegie’s, so that tenants on that side of the Carnegie Building would see nothing but the wall of the Frick Building out their windows. Then Frick bought the lot on the south side of the Carnegie Building and had Burnham design the Frick Annex (now the Allegheny Building), another taller skyscraper that blocked in the Carnegie Building on that side.

Across narrow Fifth Avenue from the Carnegie Building was St. Paul’s Cathedral. Frick made the Catholic Diocese of Pittsburgh an offer it couldn’t refuse, and then he tore down the cathedral to replace it with the most magnificent shopping arcade in the United States—blocking in the northern face of the Carnegie Building. Ultimately the Carnegie Building became a stuffy and claustrophobic place, and in the 1950s it was finally torn down and replaced with the nearly windowless Kaufmann’s Annex.

This arcade, the Union Trust Building, was designed in the office of Frederick Osterling, who usually gets credit for it, although it appears that the actual design was by Pierre Liesch, who worked for Osterling. Frick and Osterling had a falling-out, too, and Frick decided to ruin Osterling, whose major commissions downtown dried up. (On the other hand, when Osterling died years later in the middle of the Depression, he left an estate worth a million and a half, so he probably didn’t need the work.) But the building remains, and it generated legends.

From street level you can just make out these odd constructions on the roof.

What are they? Where there is an urban phenomenon, there is an urban legend to explain it. Pittsburghers remembered that Frick had torn down a cathedral to put up this building. The story is still told today that the Catholics had extorted an agreement from Frick: he could have the lot only if he included a chapel somewhere in his building, where he could retreat to repent privately of his many sins. If you look up, Pittsburghers say, you can see the chapels where Frick did his repenting.

This legend is a tribute to the constitutional charity of Pittsburghers, who are so charitable that they can imagine even Henry Clay Frick repenting.

But as our friend Father Pitt wrote sixteen years ago, “The truth is more prosaic and yet more impressive as an architectural accomplishment: the chapel-like structure houses the mechanics for the elevators and other necessities that normally make ugly blisters on the roofs of large buildings.”

Nevertheless, the “chapels” are such a distinctive feature of the building that the current owners have floodlit them. They are the brightest object in downtown Pittsburgh at night, and the bright lighting only feeds the legends.

From DR. BOLI’S UNABRIDGED DICTIONARY.

Afflatus (noun).—The flatulence of a deity.

PINK.

Why is the world so pink?

Dr. Boli will tell you. It is because the American people are suckers.

These corporations are spending quite a bit of money on pinkening the environment so that we will see that they care about breast cancer. That money could, of course, be spent on research to cure breast cancer. But instead it is spent on pink. Our corporate masters want us to think well of them, because it makes us easier to manage; and they have discovered that turning on the pink lights, which everybody can see, is more effective at making us think well of them than donating an equivalent amount of money to medical research, which is not as visible no matter how many press conferences they call. We are suckers. We believe in the goodness of the corporation if it puts out a sign that says “We are good.” So corporations fund the lighting contractors, and the medical researchers starve.

FROM THE ILLUSTRATED EDITION.

From DR. BOLI’S UNABRIDGED DICTIONARY.

Politics (noun).—Any organized method of deciding how many inoffensive bystanders must die in order to keep or gain power for a privileged class. (A disorganized method is called a riot.)