“Sunlight and Shadow,” by Constant Puyo. Or is it by a machine?

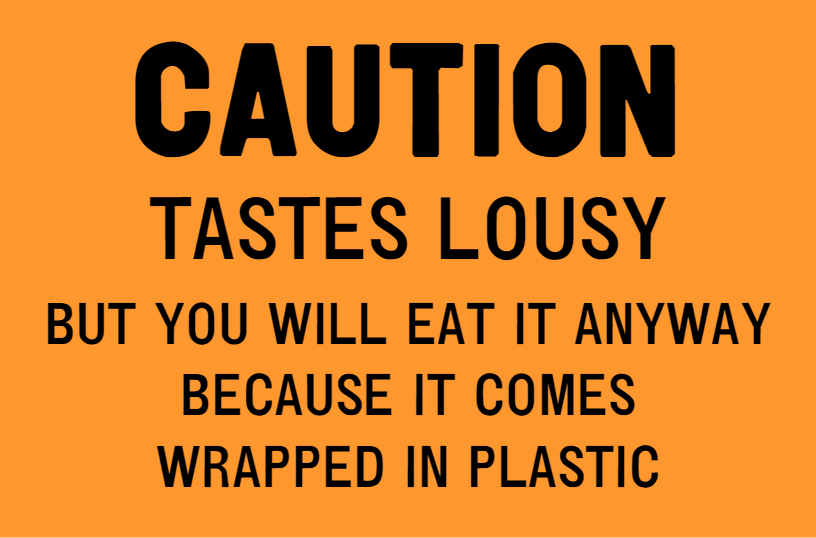

The world seems to be settling on a technical term for the writing, images, and videos produced by artificial intelligence, and it is a good one: “slop.” The word feels good in the mouth when one is trying to convey the empty slickness of this effortless filler. But we will see more and more of it, because it is effortless, and because, as H. L. Mencken either said or ought to have said, no one ever went broke by underestimating the taste of the American people.

The sudden rise of content by artificial intelligence has given us a chance to pour more kerosene on the ever-smoldering debate over the nature of art. What is this thing called “art,” anyway, and can a machine ever produce it? The general acceptance of the term “slop” gives us a broad hint at one popular answer to the second question. But the first question remains unanswered, probably because it is unanswerable. Dr. Boli has always been inclined to define “art” in a purely mechanical way, thus leaving room for the possibility of bad art as well as good art. But the strictly mechanical definition does not seem to satisfy most people: when they ask “Is it art?” they clearly assume that a work has to prove itself worthy of the name “art.” Thus the debate over whether art produced with artificial intelligence can ever be called “art” is really a debate over whether AI art will ever be good enough to be called art.

Now, artificial intelligence is young—amazingly young. It was born yesterday; can we even predict what it will be like tomorrow? And if not, how can we predict its mature state?

It is not just artificial intelligence that changes quickly. The humans who use it are learning and adapting, too. We have only begun to figure out what we can do with AI—or what it can do with us.

Having spun around in a circle, we are back at the question we started with. Can a machine ever produce art?

Here Dr. Boli’s long memory gives him a different point of view from that of the average Internet blitherer. Dr. Boli’s own blithering is informed by a better acquaintance with the past two centuries or so, and in this case he remembers that we have faced exactly this question before. It took us more than a century to answer it, and it was never answered definitively. But the consensus of opinion has been that, yes, a machine can produce art, when that machine is a camera.

To anyone who has lived through both revolutions, the resemblance is hard to miss.

Previously, making a picture had been a skill learned with long and laborious practice. Then along came the machine, and the skill was irrelevant. Why learn to draw when the machine can make perfect images for you? There was much grumbling about whether such laziness ought even to be allowed, and much hand-wringing about the future of Art.

With no alteration at all, the paragraph above can be made to apply to the coming of photography in the early nineteenth century or the coming of artificial intelligence two centuries later.

But life and art continued after the camera came to be, and they will continue after the rise of the bots. Furthermore, a place was found in Art for photography, and—much as we might prefer to hope otherwise—a place will probably be found in Art for artificial intelligence.

It is far too early to say what that place will be. But we can at least reason by analogy.

The first artistic photographers—the first ones, that is, who demanded a place among the fine arts for photography—tried to make their pictures look as much like paintings as camera and chemistry would allow. They had no other standard by which to judge a good picture. But after a while—a long while—photographers began to appreciate what made their art different from painting. The very things that had seemed defects to overcome in the eyes of the early generations became effects to be controlled and put to artistic use.

Depth of field, for example, is a property of lenses. A lens sees things in sharp focus only at a certain range of distances. The same is true of the human eye, which is a lens, but it is not really true of human perception, because our eyes are always changing focus to take in whatever our brains tell them to focus on. It takes deliberate and unnatural effort to focus on one thing while being conscious of another. Therefore it never occurred to painters before photography to emphasize the subject by blurring the background; and therefore the early photographers mostly considered depth of field an unfortunate limitation of their equipment. But later photographers came to rely on that limitation for some of their best effects; and today, if you decide to step up from random snapper to photographic artist, the first thing you will learn is how to control depth of field and make blur work for you. (The second thing you will learn is to say “bokeh” instead of “blur.”)

Here is just one example of how the things that made photography different from painting or drawing became tools in the hands of competent artists. Photography even developed its own artistic clichés—ask our friend Father Pitt sometime what he thinks about moving water and slow shutter speeds.

Thus we see that, although the machine produces the image, we have come to accept the person in control of the machine as an artist.

It seems likely that the same will be true of creations made with the help of artificial intelligence. We probably will not call it art if it is produced by simple prompting. We do not call a snapshot of someone’s birthday cake “art” unless a good photographer has put thought into the lighting, the composition, the colors, and (of course) the depth of field. But it is easy to imagine an artist with a vision arranging images generated by AI to form a scene matching the vision in the artist’s imagination.

In fact, the bureaucrats in charge of copyright registration have already made exactly this distinction. A report of the Copyright Office (PDF) concludes that AI productions can meet the requirements for copyright “where AI is used as a tool, and where a human has been able to determine the expressive elements they contain. Prompts alone, however, at this stage are unlikely to satisfy those requirements.” So an image generated by an AI prompt cannot be copyrighted, because even complex prompts do not generate the same image twice in a row; but an arrangement of AI-generated images can be copyrighted, because the arrangement is the original work of a human artist. “Whether human contributions to AI-generated outputs are sufficient to constitute authorship must be analyzed on a case-by-case basis,” so if you are a young person looking for a career, now is a swell time to go into copyright law.

For the moment, then, Dr. Boli is inclined to say that the question of whether there can be AI art is an updated version of the question of whether there can be photographic art. And he will give the same answer. Most images produced by the machine will not be artistic, just as most pictures snapped with a phone camera are not artistic, or—for that matter—most scribbles with a pencil are not artistic. But it will be possible for an artist to use the machine as a tool for making art.

Of course, none of this answers the question of whether an artificial intelligence is by itself intelligent enough to produce art, leaving the human manipulator out of the question. But when the bots have taken over and relegated us to menial maintenance tasks, they will have to answer that question themselves, and Dr. Boli sees no reason to give them a head start by answering it for them now.