CHAPTER 24.—EUROPE DISCOVERS THAT THE REST OF THE WORLD IS JUST SITTING THERE.

—

Obviously the shortest way to the East, in spite of that old crank Columbus, was by going east. The only problem was that the Mediterranean ran out of water before you got to the really profitable parts of the East, so you couldn’t get there by ship; and if you tried going by land, the wicked Turks would stop you. The Turks were such a formidable obstacle, in fact, that Europeans thought almost any sea route would be preferable to trying to push through the Turks.

Here is where the Portuguese come back into our history. Each generation of Portuguese sailors went a little farther down the west coast of Africa, turning back with the report that there was still more Africa down there; but they still treasured the hope that they would eventually run out of Africa and find a way to the East. Meanwhile, they looted whatever was valuable on the coast and set up trading stations. One of the valuable commodities they found on the African coast was slaves, and thus they began the transition of slavery from something Europeans did to Europeans and Africans did to Africans to something Europeans did to Africans.

Just before Columbus came to the Portuguese court to peddle his screwball idea of going west to get to the East, a Portuguese ship had finally reached the point where there was no more west coast of Africa, rounding the Cape of Terrifying Violent Death in 1488. The Portuguese marketing department, eager to encourage more sailors to make the trip, renamed the place the Cape of Good Hope, and a Turk-free way to the East was open at last. Thus the Portuguese were in a good position to give Columbus the raspberry. In 1498, just a few years after Columbus reached the Wrong Indies, Vasco da Gama arrived in India, where, following standard European practice, he kidnapped a few natives to prove he had been there.

Thus Spain and Portugal were both busy at the same time exploring the world and looting whatever they found. It was not possible for two neighbors to send ships in all directions without sometimes getting into an argument about who first encountered some peaceful and prosperous culture, and had therefore earned the right to obliterate it. Eventually the squabbling got so noisy that the pope couldn’t hear himself think; so he grabbed a world map and a grease pencil, ran a fat line right down the map from top to bottom, and told Spain and Portugal to stay on opposite sides of it and stop poking each other. He had intended to give the Old World to Portugal and the New World to Spain, but since he drew the line without looking, it ended up going straight through South America, which meant that Portugal got Brazil.

Spain and Portugal had monopolized most of the New World from Mexico south, but North America was still uninhabited, except (of course) by the inhabitants, who didn’t count.

This was a sore temptation to the other nations of Europe. Elizabeth was queen in England, and when some capitalists approached her with the idea of setting up a colony in North America, she granted them a charter—with the rather canny provision that the rights would revert to the Crown if they failed to set up their colony.

So, in 1584, Sir Walter Raleigh sent out an expedition to found a colony he named Virginia, after having rejected Celibacia and Spinsterburg, in honor of Queen Elizabeth’s unmarried state. It is worth noting that Sir Walter himself was not such a fool as to sail with the expedition; and indeed if he had followed his sensible policy of exploring by proxy for the rest of his life, he might have been much better off.

The usual plan of European adventurers headed for the New World was to arrive, spend a few weeks scraping the gold off the streets, and then go home to retire as the wealthiest men in the kingdom. This explains why the plans for the Virginia colony were a bit haphazard. The colony was not a success. It would have been a miracle if it had succeeded. The colonists at Roanoke seem to have assumed that they were setting up shop in the Land of Catered Five-Course Meals. When the catering failed to appear on schedule, the hungry colonists tried moping. When that, too, failed to produce the desired results, they sent a ship back to England for food, telling the captain that they would be very cross if he didn’t return with the provisions by tea-time.

Meanwhile, the American tribes kept trying to explain to them where food comes from. “You stick the seed in the ground,” they said slowly and distinctly. “Three months later, you’ve got corn. Takes patience, but works.”

Instead of showing up by tea-time, the ship from England dawdled for three years with this and that—a Spanish Armada here, some piracy there (as pirates, not as victims). By the time it finally got back to the Roanoke colony, all that was left of it was the single word “Croatoan” scribbled in a tree trunk, a mystery that generations of historians have delighted in obfuscating further. The most recent research suggests that it was a botanical label.

What did happen to the Lost Colony? One suggestion is that the colonists finally wised up, went to live in the comfortable houses of the Algonquian towns nearby, and left offspring who still infest local historical societies in North Carolina claiming to be descendants of the Lost Colony. Another suggestion is that they tried to steal food from their neighbors so many times that their neighbors, in spite of their original friendly intentions, finally squashed them like cockroaches.

Historically speaking, however, the most plausible theory is that they lived with the Indians for a while, and then were massacred by Powhatan. This theory is plausible because, when later English settlers asked Powhatan whether he had seen any remains of the Lost Colony, he answered, “Oh, yes, I remember them. Killed ’em all. If you want something done right, you know, you have to do it yourself.” After this rather blunt statement, most of the other theories about what happened to the Lost Colony probably qualify as wishful thinking.

In spite of the failure of the Roanoke colony, Virginia—which is to say all of North America between Newfoundland and the sickly Spanish colony in Florida—now belonged to the English, because the English said so. (The American residents were not asked to render an opinion.) About twenty years later, this time under King James I, another group of English settlers headed for Virginia. They were determined to repeat as closely a possible all the mistakes of the Roanoke colony, but by accident they left out a few, and so just barely survived.

Their leader was one Captain John Smith, who was christened with the most unimaginative name ever foisted on a man of destiny. There were times when he must have wondered whether he had any destiny ahead of him at all. Whenever he signed the register at an inn, he was greeted with derisive snickering. When he tried to sign up for Google Plus, the site kept demanding his real name. No wonder he finally decided to chuck it all and go to sea.

When he reached Virginia, Captain Smith met our old friend Powhatan, destroyer of the Lost Colonists. King Powhatan decided to apply his usual method of pest control to Captain Smith. But he had one fair daughter named Pocahontas, the which he loved passing well. When she threw herself across the condemned prisoner and begged for his life, Powhatan, perhaps making the biggest political blunder of his career, shrugged and spared the man. Then Pocahontas went off and married John Rolfe, because all those pasty pink-faced Englishmen named John looked alike to her.

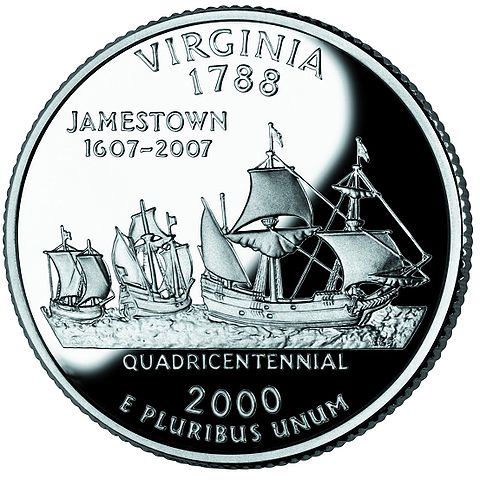

The English colonists built a rickety little fort that they named Jamestown, which is commonly described as the first permanent English settlement in North America. But “permanent” is a slippery idea. If you go to Jamestown today, you will see a weed patch with a church, so obviously “permanent” isn’t all it’s cracked up to be. It never amounted to very much, even though the colonists soon began rather grandly referring to it as “James City” (that part of Virginia is still James City County to this day); when the capital was moved to the healthier and more defensible Williamsburg, James City withered away.

The Virginia colonists died like mayflies, but just enough of them survived long enough that they finally figured out how to grow food. After that, the Virginia colony actually began to grow, and in 1619 the first Africans arrived, beginning the long and colorfully hospitable Southern tradition of welcoming guests from the African continent and finding useful employment from them.

Just a year after that, another group of colonists set out for England’s American dominions. This was, however, a completely different sort of people. The original Jamestown colonists had been incompetent because they were greedy layabouts who expected to get rich by scooping the excess gold off the streets of the New World. The Plymouth colonists were incompetent because they were religious fanatics, which is an entirely noble reason to be incompetent. No wonder, then, that the average American schoolchild has never heard of Jamestown, but thinks that the Pilgrims came over with Columbus and immediately wrote the United States Constitution between courses of Thanksgiving dinner.

Since the story has been told so often and so colorfully, Dr. Boli will not attempt to give you a full account of the Plymouth colonists. A group of dour and gloomy religious fanatics, too grim for English soil, tried being dour and gloomy in Holland for a while, but found the place entirely too cheerful. They came to America to establish a colony whose founding principle was dour gloom, and they succeeded beyond their wildest dreams. Here, in the land of liberty, they were free at last to punish the malefactors who enjoyed life. And we may safely leave them under their portable cloud for the moment.

Fourteen years after the Pilgrims landed at Plymouth, another English colony was planted at St. Mary’s City just upstream from the Chesapeake. This was a group of English Catholics, and they called their colony Mary-land after…um…after Henrietta Marie, Charles I’s queen. No, seriously, that was actually what they said, and maybe they really did expect somebody to believe it. The Maryland colony guaranteed freedom of religion, which was the silliest idea anybody had ever heard of. Most of the history of Maryland in the 1600s is a series of maneuvers intended to restore the lawful right of persecution in the erring colony. What with the constantly shifting parade of governments back home, it was sometimes difficult for the colonial authorities to know whom to persecute this month; but even if the authorities were lax, they could always rely on local terrorist gangs to persecute somebody or other.

These colonies—Jamestown, Plymouth, and St. Mary’s—all went through times of dreadful hardship when most of the colonists died. In 1681, however, one bright colonist had the idea of setting up a colony where most of the people would not have to starve to death.

William Penn was a Quaker, a member of a religious sect that was a nuisance in England. Quakers were notoriously honest, which gave them an unfair advantage in business that was hotly resented by other merchants. They believed that every man ought to follow his own conscience, which was insulting to anybody who didn’t have one. They were peaceful, and refused to fight back when persecuted. Really, how can you live with people like that?

King Charles II owed William Penn a bit of money, and what with one thing and another he had left his wallet in his other suit. So he granted Penn a bunch of land in English North America that belonged to him by right of saying it belonged to him. “That ought to take care of it,” he said, “but if it’s not enough, come back and I’ll give you Jupiter and the Pleiades, too.” So the debt was settled, and Charles was pleased with himself: it could not have escaped him that there was a considerable advantage to having the Atlantic Ocean between decent people and those creepy Quakers. He called the grant “Pennsylvania,” a silly name that embarrassed poor Penn every time he heard it.

Penn proceeded to set up his colony on the most absurd basis possible. First of all, even though the king himself had granted him the land, Penn insisted on treating with the Americans for any land he took from them. Yes, as mad as it sounds, William Penn believed that the Indians owned the land, and he had no right to it until he had made an agreement with them.

It seems as though it would be hard to come up with any idea more absurd than that, but Penn managed it when he declared that religious freedom would be the law in his new colony. You could be Quaker, or Calvinist, or Jewish, or Roman Catholic, or even Anglican, and you still had the same rights as everybody else. It had been tried before in Maryland, and everybody knew it was a miserable failure.

Penn also brought over productive workers instead of religious fanatics or lazy gold-hunters, so his new city of Philadelphia began to thrive as soon as it was planted. In fact, Penn’s colony never went through a Starving Time, which seems a little unfair.

We have spent quite a bit of time with the English in North America, but we should not suppose that the rest of the world lacked the civilizing benefits of rapacious European adventurers. The Spanish grabbed the Philippines. The Dutch infested Indonesia and various parts of the East Indies and were beginning to form a large blot on the southern tip of Africa. The Portuguese continued to snap up bits of Africa and India, but in the latter they were stymied by the British, who were beginning to stumble around in India as well.

Unlike the Portuguese, who had genuine colonial ambitions, the British had no grand idea of conquest. British capitalists would make a comfortable business arrangement with some local ruler and enjoy the profits for a while; then their pet ruler would inevitably be attacked by his neighbor, and his English friends would realize that their profits were in jeopardy, so of course they had to step in as managers and help out a bit. When the attacker was pounded into dust, the English had two profitable little kingdoms instead of one. And so it went, until the British East India Company controlled almost the entire Indian subcontinent. It was probably the first (though certainly not the last) great land empire controlled by corporate executives.

The history of British India is colorful and full of incident, and it would make a fine book of its own. The focus of world history, however, has moved to North America now, and it will be necessary to recount some of the events that led to a titanic struggle for the continent—a struggle that would determine the fates of two empires and, more importantly, result in the foundation of Pittsburgh.

—

The chapters previously published:

FROM THE CREATION OF THE UNIVERSE TO THE DAWN OF CIVILIZATION.

THE DEFINITION AND CHARACTER OF CIVILIZATION.

THE ANCIENT EGYPTIANS, FURNISHING AND DECORATING THE AFTERLIFE SINCE 3150 B.C.

THE LESS MARKETABLE ANCIENT CIVILIZATIONS.

THE ISRAELITES DISCOVER MONOTHEISM AND SPEND MOST OF THE REST OF THEIR HISTORY TRYING TO BACK OUT OF IT.

THE ANCIENT GREEKS LIVE THE EXAMINED LIFE.

THE ANCIENT GREEKS INVENT HISTORY.

ALEXANDER RUNS OUT OF WORLDS TO CONQUER.

WHILE ROME CONQUERS THE WORLD, GREECE CONQUERS ROME.

CHRISTIANITY RUINS EVERYTHING.

THE ROMAN EMPIRE DECLINES AND FALLS FOR 1500 YEARS STRAIGHT.

BARBARIANS EVERYWHERE.

CIVILIZATION DESTROYS CIVILIZATION.

NOTHING HAPPENS IN THE DARK AGES.

CHARLEMAGNE TURNS ON THE LIGHTS.

MORE FUN WITH BARBARIANS.

WHAT THE MIDDLE AGES WERE IN THE MIDDLE OF.

THE CRUSADES ARE WHOLESOME FUN FOR EVERYONE.

FRANCE CONQUERS ENGLAND; OR, ENGLAND CONQUERS FRANCE.

EUROPE PRESSES THE RESET BUTTON.

THE REFORMATION ELIMINATES EVIL FROM THE WORLD.

EUROPEANS DISCOVER AMERICA; AMERICANS DISCOVER EUROPEANS.

IT TURNS OUT THE PROTESTANT REFORMATION LEFT SOME UNFINISHED BUSINESS.