Posts filed under “Art”

A TEMPLE OF OBJECTS.

An object.

As you leave the exhibit, you come to this sign, in which the museum apologizes for making you suffer through all that art. We duplicate it here for the purpose of comment and criticism.

Epilogue. As single-collector institutions, The Frick Pittsburgh and The Frick Collection are invariably linked to their individual founders. Both museums originate from a place of privilege, built on the backs of laborers in western Pennsylvania. Although genuine in the impetus to create something for the public good, many of the principles that guided the founding of our institutions no longer ring true. Today, museums strive to be centers of creativity, thought, and conversation, rather than temples of objects chosen by (and to represent) an elite few.

Here are a few essay questions on our assigned reading.

1. If museums are not to be temples of objects, then where should the objects be?

2. If the objects in museums are not to be chosen by an elite few—for example, by the vanishingly small number of intellectuals who have studied the history of art—then by what sort of democratic referendum are they to be chosen?

3. What will happen to the objects once we succeed in transforming our museums into centers of creativity, thought, and conversation? Will the objects go back into the hands of private collectors who will exclude the general public from viewing them?

4. If a museum is to be a center of creativity, thought, and conversation, how is it different from a coffeehouse? Is it just that the coffee is worse?

Dr. Boli will be very straightforward here. In his opinion, this is simple old-fashioned Yankee anti-intellectualism dressed up as fashionably enlightened righteousness. It is as silly to say that the “elite few” should not choose art as it is to say that a trained auto mechanic should not rebuild your transmission, or that a trained surgeon should not remove your appendix. What, you think I’m not good enough to perform an appendectomy? Just because I’m a cashier at the Circle K? I thought we were done with that kind of snobbery. It’s so nineteenth century.

It is also particularly antidemocratic anti-intellectualism, because of course the logical consequence of abandoning the idea of the museum as “a temple of objects” is that the δῆμος shall no longer have access to the objects. In the Frick Pittsburgh’s permanent collection you can see a colossal landscape by Boucher, and a portrait by Reynolds, and another by Gainsborough, and a whole room of early Italian Renaissance devotional art, and it’s free, because Helen Frick endowed the museum so that the public could always have free access to her art collection. The cleansing of the temple would mean that the art student who had taste but no money would no longer have that privilege.

What would our hypothetical impoverished art student see instead? Beside the “Epilogue” was a station with a table where visitors could think, exercise their creativity, and join the conversation by writing their thoughts on sticky notes and sticking them on the wall. This is what you should see in a museum, instead of stuffy old Rembrandt, who looks sad for some reason.

One of the questions you could choose to answer on sticky notes was “What would you like to see in a museum?” After thinking for a while, Dr. Boli picked up a pencil and wrote, “A temple of objects, chosen by an elite few.”

Portrait of a Man in a Red Hat, by Titian.

MOCK SHUTTERS.

Now here is a house with mock shutters.

These are advertised as things that will “add sophistication to your home,” and for a long time Dr. Boli simply could not figure them out. It was not just that they were not functional; it was that he could not understand what the people who installed them thought they were.

If they were conceived of as illustrations of shutters, the way some people wear a shirt with a picture of a jacket and tie on it, that might make sense. You cannot afford the expense of hinges, but you want your neighbors to think that you have the kind of money it would take to put hinges on your shutters.

But obviously they are not conceived of that way. Take a look at the second picture again. Imagine the shutters shutting. Imagine how much of the windows on the first floor they would cover. When you have stopped laughing, try to explain what the people who installed them thought they were installing.

For decades this mystery has bothered Dr. Boli. What do these mock shutters represent? What idea are they meant to convey to us? What is the message of the plastic paste-on shutters?

But at last a reader and friend gave Dr. Boli the explanation he had been waiting for. Shutters, she said, are air quotes for windows. They tell us, the spectators, “This decorative glass-covered hole in the wall is a ‘window.’ In ancient times, before LED bulbs, ‘windows’ were used to admit ‘light’ into the house, and some of them could even be ‘opened’ to admit ‘fresh air,’ a substance on which our ancestors placed much value, though the reason for it has been lost in the ‘mists’ of ‘time.’ Today we honor the traditions of our ancestors by placing ‘windows’ in the walls of buildings of the higher class.”

This is the only satisfactory explanation for mock shutters that Dr. Boli has ever heard. But it does bring up another question: What is the overlap between people who put mock shutters on windows where they could not possibly shut and people who constantly use air quotes in conversation? Dr. Boli has begun to suspect that a Venn diagram of those two groups could be made with one circle.

Meanwhile, now that we have made some progress in the mystery of the mock shutters, perhaps another reader will be able to explain rear spoilers on front-wheel-drive cars.

The photographs are generously provided by Father Pitt.

ART CORNER.

LOUIS SULLIVAN AND THE ALLITERATIVE SLOGAN.

“

What would Louis Sullivan have thought of that?

Over at Ink, we published an essay entitled “Form Follows Function, and Ornament Follows Form,” in which we suggested,

If you had asked Mr. Sullivan whether he meant that the bare outlines of form must be presented to the world naked and without ornament, he would have told you he did not mean that, possibly including some colorful Chicago language for emphasis. He spent his whole career trying to come up with a native American system of ornament that would beat the pants off the stale European imports. We can be sure that he did not mean to leave us an inviolable commandment against any kind of decoration.

However, we do not need to speculate on what Louis Sullivan would have thought of alliterative slogans. Let us ask Mr. Sullivan that very question.

When a group of progressive-minded architects grew discontented with the conservatism of the American Institute of Architects, they seceded and formed the Architectural League of America, rallying under the slogan “Progress before Precedent.” The Brickbuilder asked a number of well-known architects “for an expression of opinion upon the general subject, considering not only whether the maxim of the League finds favor with the coming men of the Middle West, so much as what is the best view to take of the subject itself.” Poorly phrased, perhaps, but they got some big names to respond. One of them was Louis Sullivan. It appears that alliterative slogans made him grumpy and pessimistic.

In my judgment a maxim or shibboleth, such as “Progress before Precedent,” is in itself neither valuable nor objectionable.

The broad question involved in the advancement of our art is one that lies specifically with the rising generation, and it will answer in its own way,—theory or no theory, maxim or no maxim.

If the coming men possess in a high degree the gift of reasoning logically and unwaveringly from cause to effect, the rest, practically without qualification, will take care of itself.

The present generation does not possess this gift, nor does it trouble whether or not: hence chaos. That the younger men have it is, as far as I can observe, quite conjectural. Talk and good intentions we have, but talk and good intentions do not build beautifully rational buildings. Talk may be had for the asking and good intentions become pavements here as elsewhere; but delicate clarity of insight, sturdy singleness of purpose, and adequate mental training are notably so rare in our profession as almost to be freakish. We have muddy water in our veins.

I am an optimist, and live ever in hope; yet what I wish and what I see are by no means identical. Still, doubtless, there is a ferment working that we wot not of. I would discourage no one in the belief.

Finally, when all is said and done, the architectural art is a proposition too easy or too difficult, just as you choose to regard it. It is an art as yet without status in modern American life. Practically, it is a zero.

HOW MUCH NAZI CAN WE TAKE?

We also mentioned that he harbored ambitions of becoming Nazi dictator of Hungary.

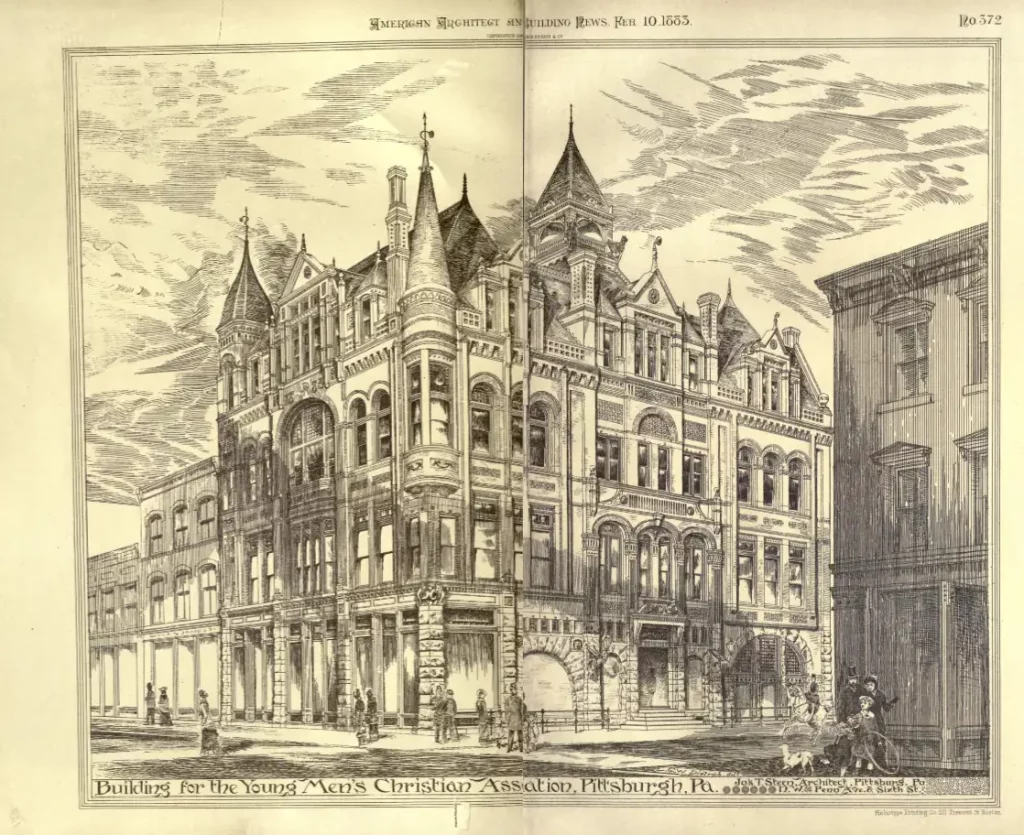

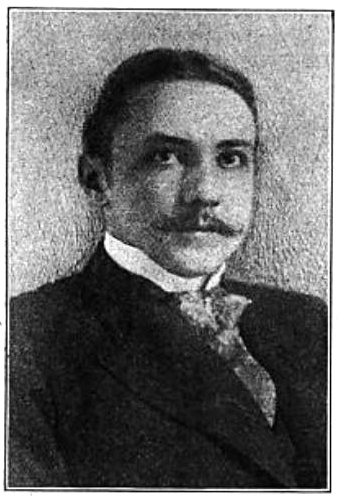

Our friend Father Pitt is still occasionally poking at the life of the mysterious Titus de Bobula, and he has dug up quite a few more curious facts about the man. For example, a pictorial feature in an architectural magazine documents an astonishing mansion he designed in the Bronx—so far the only post-Pittsburgh construction by de Bobula that has come up in Father Pitt’s extensive research. We are sad to say that it has disappeared from its perch overlooking the junction of the Harlem and the Hudson, but the photographs that remain show a prodigious imagination at work.

Father Pitt has also dug up, in English translation, the exact text of the “treaty” between Adolf Hitler and de Bobula and his partner in Hungary. That document, in fact, was what caused de Bobula’s coup to fail: his courier was on his way to Munich to have it signed by Hitler when police stopped and searched him on the train. But if the plan had gone through, here is what would have happened. First, Hitler would take over Bavaria. Then swastika-wearing Bavarian troops would march into Hungary to help de Bobula and company overthrow the government there. Then they would round up all the Jews.

You can read all about Titus de Bobula’s ever-weirdening life in Father Pitt’s greatly expanded article about him. But the case of Titus de Bobula poses an important question in the starkest possible terms. How much can we separate art from the artist who made it? How much Nazi can we take?

On the one hand, Titus de Bobula the architect was an artist of unignorable talent. As Lu Donnelly says on the Society of Architectural Historians site, “De Bobula is the most original force to have emerged from the many immigrant groups who enriched Pittsburgh with their artistic heritages.” Pretty strong words to speak about the city of famous Slovak Andy Warhol, but she makes a strong case.

On the other hand, Titus de Bobula later became a full-blown Nazi who would have started the Holocaust ahead of schedule if he had had his way. (We may find it a little ironic that, in his earlier Pittsburgh years, he drew plans for the new Tree of Life synagogue as one of the entrants in an invitation-only competition. It would have been even more grimly ironic if he had won.) Nor did he have the excuse of being swept along by the tide of popular mania: Titus de Bobula was an early leader in the movement, or at least he fancied himself one.

Even without the sudden swing to fascism, he seems to have been an awful person generally: his wife’s uncle Charles Schwab called him “dishonest, incompetent, and a blackmailer.”

So do we repudiate the art because the artist was a Nazi?

Well, we could do that. But we run into the problem that most great artists are awful people. The best artists tend to have a streak of self-centeredness in them, coupled with an absolute confidence that they know what is good and correct, and a strong willingness to enforce their ideas given half a chance. Our job as citizens of a representative government is to make sure they do not get half a chance. But it would impoverish our museums if we decreed that the artists represented in them had to be of morally upright character.

Of course, this is not necessarily a binary proposition. We don’t have to accept all the rotten apples or none. We could decide that there are degrees of horribleness, and draw a fuzzy line somewhere in the middle. Unfaithful to his wife: pass. Attempted Holocaust: fail.

But it is at least a decision we should make knowing that we are making a decision. If we unthinkingly reject every artist who offends our moral sense, we are bound to run out of artists before we even notice the shortage. If we plan to reject any artists on any moral grounds at all, we ought to decide in advance what our standards are going to be.

Here Dr. Boli will admit to being an extremist himself. He believes in a complete separation between art and artist. This means that we do not even consider the moral character of the artist. If Adolf Hitler draws us a nice picture of a cow, we say, “That’s a nice picture of a cow. I hate Hitler’s guts, but this is a nice picture of a cow.” It also means, incidentally, that the artist has no control over the meaning of the art once it is launched into the world. The artist has a moral right to tell us that his art means this, but we have an equal right to say that it doesn’t, and that the artist has misunderstood his own work. To say otherwise is to say that critics have no right to exist, which would certainly please plenty of artists.

Dr. Boli will even try to find something nice to say about Nazis, just to demonstrate the principle of separating the work from the worker. How about this? Of all the extremist movements of the twentieth century, the Nazis had incomparably the best graphic design. Put your socialist-realist posters away, Soviet propagandists: you just can’t match the Nazis for style. There. That took some effort, but we found something nice to say about Nazis. We have probably exhausted the entire world’s supply of nice things one can say about Nazis, but we did it.

What Dr. Boli is saying is that the question of whether we can swallow the Nazi when we look at Titus de Bobula’s work should not come up, because the art is a separate thing from the artist as soon as the art is presented to the public. You don’t have to swallow the oyster to wear the pearl. Nor, if it comes to that, do you have to wear the pearl to eat the oyster. The pearl grows from a slimy mollusk, but it is not slimy. The First Hungarian Reformed Church of Pittsburgh comes from a Nazi con man, but it is not a Nazi.

THE FAMOUS STEEN GUARANTEE.

YOU DIDN’T KNOW YOU WERE LOOKING FOR IT, BUT…

Do you remember fifty years ago, when the trade name “Muzak” stood for all that was soulless and intolerably commercial in music? Do you remember the experience of walking into every commercial establishment and finding yourself awash in violins? Do you remember the strangely jarring sensation of hearing a symphonic rendition of “Franklin D. Roosevelt Jones” followed by a sixty-piece orchestra playing “I Wanna Hold Your Hand”?

Do you wish you could relive those days?

Well…

The S. S. Kresge chain, including its superstore offspring Kmart, had its own officially approved background music, which was shipped to Kresge stores on vinyl records (“Note: Only records bearing this label are to be used for background music over PA system”), and to Kmart stores on open-reel tapes. And you can hear hour after hour of it, because of course it still exists in the Internet Archive.

You can have all the fun you had fifty years ago dismissing Muzak as soulless, artless musical wallpaper.

And then you can fall down and weep over what we have lost.

What we have lost is profitable careers for thousands of musicians who made good money keeping up with the demand for symphonic renditions of every popular song of the twentieth century.

What we have lost is a direct connection to the era of big jazz bands, some of whose best arrangers ended up with comfortable careers creating arrangements for improbably huge orchestras—and having fun with it, knowing that no one was going to pay attention to the music, so they could do what they wanted. Ray Noble’s “Cherokee” as a march? Sure! Why not?

Above all, what we have lost is music itself. We have lost the idea that there is such a thing as pure music, music without words, because music is a thing in itself and not just a vehicle for bad lyrics.

You never know how valuable your minor annoyances are until you can’t have them anymore.

But you can have this one, because some enterprising Internet Archive user has gathered dozens of these S. S. Kresge recordings, along with training films and other paraphernalia, in a collection called, perhaps inevitably, “Attention K-Mart Shoppers.”

FOR THE REAR WINDOW OF YOUR VEHICLE.

WORLD’S LARGEST.

It’s not that big of a building. If we started a collection I bet we could buy ourselves a warehouse and make the NEW world’s largest museum dedicated to a single artist (probably Grant Wood, but I’m open to suggestions).

Dr. Boli has a suggestion. It is true that Marcel Duchamp is dead, but he shows us the way, and therefore the new world’s largest museum dedicated to a single artist should be dedicated to a living artist, but one who steals Duchamp’s shtick.

Duchamp’s “readymades” were objects found in the ordinary world, but given a title by Duchamp and exhibited as art. Obviously anybody literate enough to write a title, or articulate enough to dictate one to a secretary, can create this sort of art, though it would be helpful if our artist could have the kind of subtle and delicately ironical sense of humor Duchamp displayed when he exhibited a urinal with the title Fountain. (From Wikipedia: “Fountain was selected in 2004 as ‘the most influential artwork of the 20th century’ by 500 renowned artists and historians.” This explains the twentieth century.)

To do this again would obviously be stealing Duchamp’s shtick, but artists have been stealing each other’s shticks since the days of Phidias. There is an artistic incantation that makes everything all right: you simply say, “I am an artist of the school of Duchamp.”

Now, see how easy this makes our project of building the world’s largest single-artist museum. All we have to do is buy some big warehouse at a sheriff’s sale with all the contents in place. Then we send our pet artist in to spend a week labeling everything with whatever titles strike the artist’s fancy. When the last plaque is in place, we open our museum to the public at $25 a head, and we have a unique tourist attraction that bumps the Andy Warhol Museum down to second—and with much less effort than it would take to gather a bunch of stuffy old paintings by Grant Wood.

JOHN CAGE AND ANDY WARHOL.

The apotheosis of modern art is Andy Warhol’s Campbell’s soup can images.

Perfectly distilled cynicism: Art is Commerce, Commerce is Art. The idea of drawing a distinction between the two is now hopelessly passé. Warhol’s singularity of purpose is almost admirable. Almost.

Though I suppose we need to see who has the publishing rights to 4’ 33”, and whether Cage’s estate is rolling in dough as a result.

Dr. Boli agrees with Mr. Salmon’s assessment of Warhol. We should also remember that Andy Warhol had been a top commercial artist in the 1950s. Every trendy jazz combo had to have an album cover by Andy Warhol. We thus add another layer of cynicism: “So, ‘fine’ artists can get rich and be megacelebrities, while ‘commercial’ artists sweat in third-floor studios at the beck and call of corporate vice presidents. Hmmm…”

Andy Warhol did us an inestimable favor by pointing out that whoever designed the brand identity for Campbell’s Soup was an artist of consummate skill. As his payment for that favor, Warhol took all the money and the fame for himself, and the commercial artist got nothing. Andy had figured out who got the gravy, and he slathered himself in gravy for the rest of his life.

Visitors to Pittsburgh should make a pilgrimage to the Andy Warhol Museum. You should visit even, or perhaps especially, if you do not like Warhol very much. First, it is the world’s largest museum devoted to a single artist, and you can tell your friends you were there. Second, it has room for a whole floor of Warhol’s commercial art, and you can enjoy his distinct style and appreciate why it was so much in demand before he abandoned the field. Third, the curators understand that Andy Warhol’s greatest work was not anything he produced, but the art of being Andy Warhol, and they have done a very good job of conveying what being Andy Warhol was about.

Incidentally, it is Wikimedia’s determination that a sound file of 4′33″, which has no content whatsoever, does not rise to the level of originality required to establish a copyright under American law. The score, however, would contain directions to the performer that would be subject to copyright. It would be interesting to bring a case to court where someone created a different score that, printed, did not resemble the Cage composition at all, but produced the same result down to the duration and the “movement” divisions. A case like that might not set a precedent, but it would give the judge and lawyers involved something to tell stories about for the rest of their lives.