Posts filed under “Art”

IF THE WORLD WERE IN COLOR…

What would it look like if the world were in color?

A monochrome world has a stark beauty of its own, of course. But what if we could see colors as well as shades of grey? This is the world our old friend Father Pitt decided to visit for a little while in his newest and oddest art project. He has created a world of Imaginary Color, and has begun to populate it with pictures of the world rendered as if the world were in color. So far the collection is small, hosted on an experimental site on a free server; but it demonstrates the principle. In theory, any monochromatic picture could be rendered in colors through the same process.

What is the process? It begins with an ordinary monochromatic picture. Some of the pictures old Pa Pitt has used were taken on monochrome film, but the same results can be obtained by taking a color picture and throwing out the useless natural colors. Then each segment of the image is hand-tinted, until the appearance of a colored landscape is created.

Is there any good reason for doing this? We hope not. Both Dr. Boli and Father Pitt abide by the principle emphatically stated by Mr. Oscar Wilde: All art is quite useless.

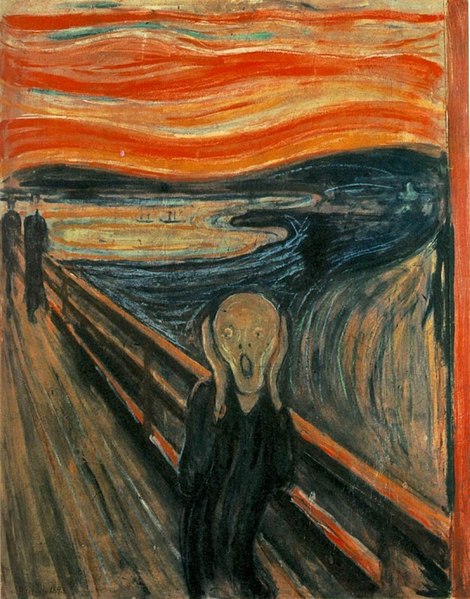

EDVARD MUNCH, ONE-JOKE COMEDIAN.

JESUS AT PLAY.

This utterly charming scene is used as the frontispiece to a history of toys from 1882, where it is labeled “Les Jouets de l’enfant Jésus, d’après une peinture sur bois de la fin du XVe siècle” (The Toys of the Child Jesus, after a painting on wood from the end of the fifteenth century).

Even better, though, is what you get when, hoping for more information about the painting, you use DuckDuckGo to look up “jouets de l’enfant Jésus” (“toys of the child Jesus”):

Now we know what Jesus was doing in the years between the return to Nazareth and the trip he made to Jerusalem at the age of twelve.

FROM THE ILLUSTRATED EDITION.

ARTISTIC GUESSING GAME.

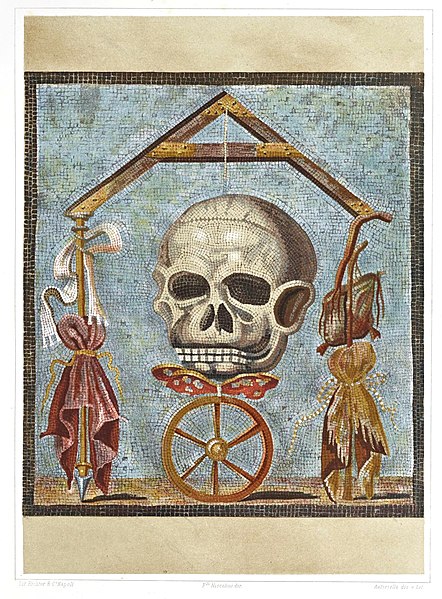

First, be delighted by this particularly skillful wood engraving from a painting by F. D. Millet (who went down with the Titanic) of a lovely ancient Roman domestic scene. Then see whether you can answer these two questions:

1. What egregiously obvious anachronism has the artist introduced?

And the second might help answer the first:

2. How might you guess immediately that an American painter was responsible for this image?

The answer:

ART CORNER.

THE MANY ROLES OF MADAME DE POMPADOUR.

Madame de Pompadour, the maîtresse-en-titre of Louis XV, enjoyed dressing up as less important people to experience the thrill of being an ordinary person who was not required to dress up all day. She was often painted in these roles. Here are some of her favorites:

Madame de Pompadour as a gardener.

Madame de Pompadour as a Vestal virgin. This was said to be her most difficult impersonation.

Madame de Pompadour as a person who might be interested in books.

Madame de Pompadour as the goddess Diana.

Madame de Pompadour as Louis XV.

Madame de Pompadour as Stonewall Jackson.

Madame de Pompadour as a bunch of fruit.

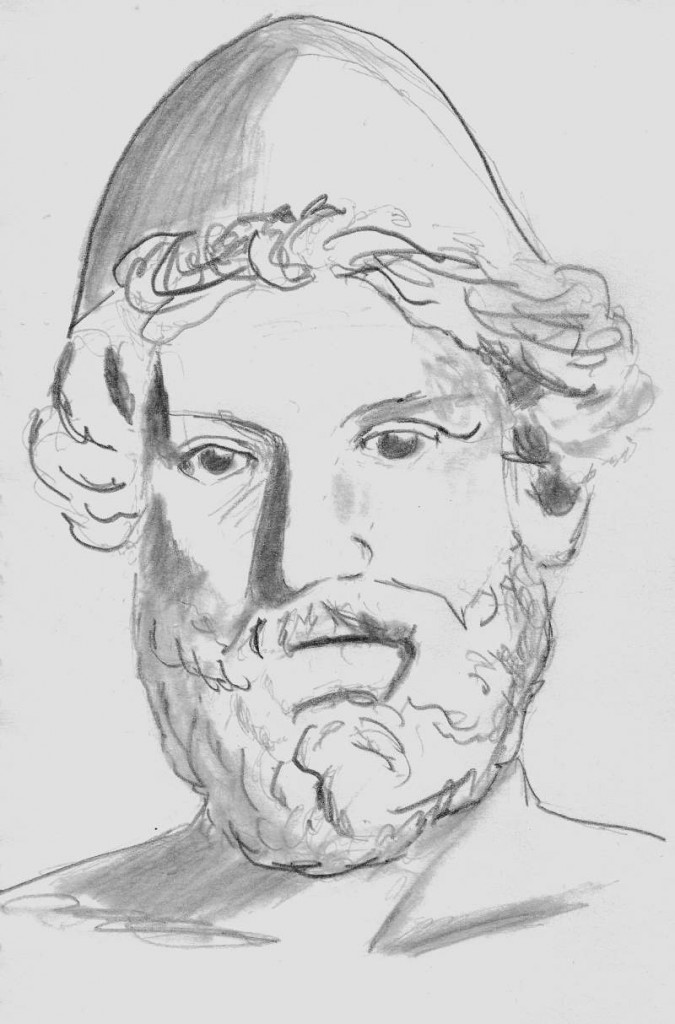

TIME-TRAVEL RETROSKETCHING.

Hephaestus, by our staff artist.

—

Hold on to your homburgs, because Dr. Boli is unveiling a new technology that shows us what the ancients actually looked like—and not just any ancients, but the Olympian gods themselves. This is a discovery that would have been impossible but for the most advanced neural network on the planet. The way it works is this: we show our staff artist a statue by some classical sculptor. Our artist then uses the advanced neural network contained within his skull to imagine what the subject would have looked like as a living person, and he quickly and lazily sketches it the way he would sketch an actual living subject. The result is as you see above: the Greek god Hephaestus as he actually would have looked if a lazy and underpaid sketch artist from the twenty-first century had been there to capture his likeness.

Obviously we cannot afford to allow this technology to fall into the wrong hands. But, since the wrong hands probably have little interest in it, Dr. Boli is not losing much sleep at the moment.

FASCINATING BUT WRONG.

Watch this video about “time-travel rephotography,” if you think you have time. Or if you don’t, allow Dr. Boli to summarize it for you. The makers of the video are convinced that they have found a way of restoring old photographs using a neural network so that we now know what the people in them really looked like.

The makers of the video are wrong.

They are wrong because they are ignorant of the art of photography. They are not entirely ignorant of the science of photography, but they have no idea how much effort went into making those photographs look exactly the way they did, and not some other way that would look more natural to a viewer used to the 21st-century clichés that define what we think is natural.

The assumption in the video is that photography is an entirely mechanical craft that simply records what is in front of the lens. Whatever light the plate or film is capable of receiving, that is what we see in the published photograph. This is an entirely wrong assumption.

For an extreme example, let us take this photograph by Robert Demachy, which was published in 1906.

This is not a print that records exactly what was in front of the lens. Demachy was an artist. The things in front of his lens were only raw materials, which had to be molded into his vision of what the portrait should look like. Demachy was well known to torture his prints with all kinds of alterations. In this case, because there are handwritten notes on the back of the photograph, we know something about what he did:

The head has been developed by affusions of warm water, the dark background removed by a slightly hard brush. The hat similarly simplified has been reduced until its existence is only just indicated.

There is not a line, blotch, shadow, or highlight in this picture that was not intended to be there. This is not a picture that was as good as it could be within the limitations of photographic technology. This is a picture that looks exactly the way Demachy thought it ought to look.

Few photographers went to the extremes of impressionism practiced by Demachy. But that does not mean that they did not know how to make their subjects look exactly the way they thought they ought to look.

Consider the matter of lighting. In the video, the “restored” faces are shown in more even lighting from multiple sources, which is fashionable in portraits today. There has been an attempt to make the primary lighting come from the same direction, but nothing has been done to block secondary sources of light. But the deep shadows in Lincoln portraits were not a mistake or a limitation of the plates. They were there because photographers of the era thought multiple sources of light were an aesthetic crime against nature. Their single-source lighting made for strong shadows, which helped the photographer delineate not just the form but also the character of the sitter. The extremes to which photographers went to perfect the lights in their studios were legendary.

I can remember when ambitious photographers, or, to speak more accurately, daguerreotypists, considered a cone light a sine qua non, and these monuments of folly rose skyward from many a city and village all over New England. Imagine one of them starting from the ceiling of the topmost story of a building, no matter how high the ceiling might be from the floor, with a circular base of say 8 feet, and extending perpendicularly into the air a distance of 15 or 20 feet, tapering in form and approximating a point at the top…. Bear in mind it was only the elite amongst the picture-makers that rejoiced in the possession of these expensive, up-to date pyramidal lights: the others got along with side windows or little flat sky-lights as befitted their humble standing. Yet these great leaders were not entirely harmonious in their views on the subject, some contending that a four-sided pyramid was even better than a conical one, and the height and taper led to warm discussion. —“The Pedigree of the Slant-Light,” by Gustine L. Hurd, in The International Annual of Anthony’s Photographic Bulletin, 1897.

So when you see Abraham Lincoln’s every wrinkle etched in shadow, it is not because photographers did not have the technology to make a better picture. It is because they applied very expensive technology to the problem of making the picture look exactly that way. That was what the people who knew Lincoln when he was alive thought he looked like.

Why is it worth bringing up this one video among millions? Because it exemplifies perfectly the dominant intellectual fault of our age. We see changes in fashion and mistake them for advances toward Truth. We honestly believe that Mathew Brady would have made his pictures with the flat, even lighting of today’s commercial portraits if only he had had the technology. Because of that belief, we reject the past as largely worthless. Any deviation from our current aesthetic or moral standards is a deviation from what is true and correct, and a sign of the ignorance of past ages. This is not an attitude unique to our age, of course; note how the up-to-date modern photographer of 1897 regards cone lights as “monuments of folly.” But our age seems more determined to repudiate the past than the people of 1897 were.

Dr. Boli has taken the trouble in this one instance to show you why it is reasonable to say that those past ages were not ignorant. They knew what they were doing. Most of what they were doing was wrong, of course; but most of what we do today is wrong, too, so we have no excuse for smugness. We went into our wrongness with open eyes. We chose it. We knew what we were doing.

If you would like to know more about what photographers of the past did to make what they, in their laughable ignorance, considered a good picture, you can start at the page on Photography in our Eclectic Library.

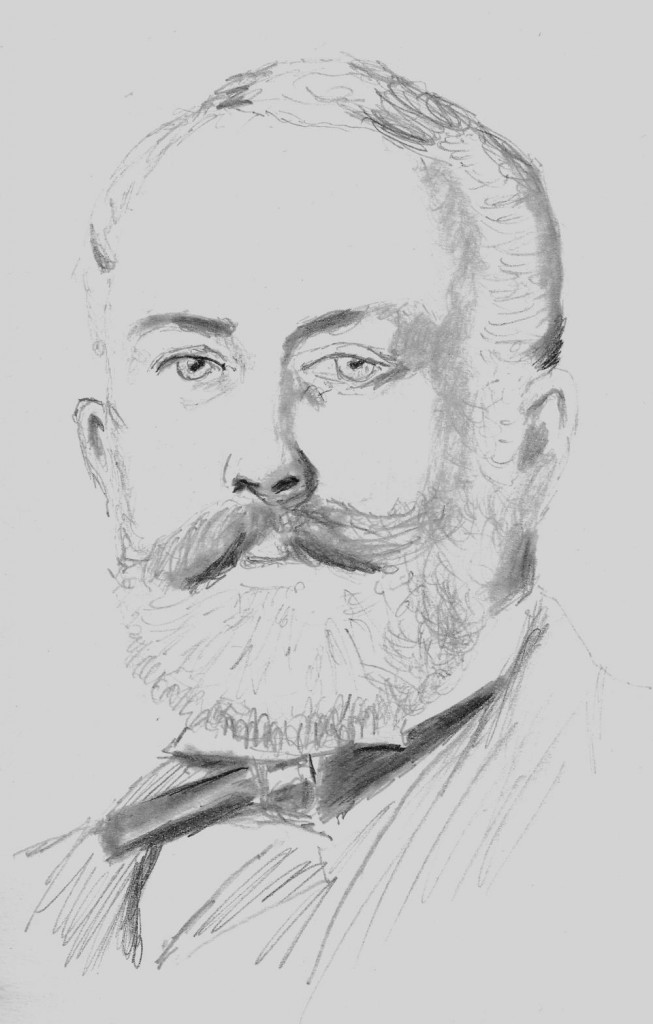

HIRING AN ILLUSTRATOR.

Henry Clay Frick, by our staff artist.

—

It is embarrassing to admit how much certain parts of the library have been neglected over the years. Dr. Boli often runs across books that have escaped the catalogue, hats or cloaks that have been misplaced for years, wandering packs of coyotes, and other phenomena that would probably not be found there if the staff were more carefully supervised. Just the other day, looking for a folio of engravings of well-known varieties of beets, he came across a man who proved to be an artist who had misplaced himself in the Flemish Renaissance department. This artist, invited at one time to use the library for his research, had been wandering in there for some years, subsisting by filching snacks left unguarded by the staff; but Dr. Boli’s appearance encouraged him to reveal himself and ask directions to the exit.

Feeling somewhat responsible for the man, Dr. Boli asked him whether he had any prospects for remunerative employment in a world that has doubtless changed a good deal since the man last saw it. The artist responded by taking up paper and pencil and dashing off a very tolerable likeness of the industrialist Henry Clay Frick, expressing confidence that Frick would be happy to commission a full-size portrait.

To this Dr. Boli was not sure how to respond. He delicately hinted that Frick was perhaps no longer in a position to make such commissions. Taking the hint, the artist asked directly whether Mr. Frick had passed on to his reward. Dr. Boli replied that he hoped the Deity was more merciful than that, but that in any case Mr. Frick had passed on, and that modern robber barons were less likely to commission portraits in oils. At this revelation the man seemed so nonplussed that Dr. Boli decided to offer him a position in his own celebrated publishing empire. It will be good to have a staff illustrator to toss off an occasional sketched portrait when an article demands one, and the artist may now continue to live in the Flemish Renaissance section of Dr. Boli’s library, on the assurance that he will not be disturbed as long as he cleans the cracker crumbs out of the folios before he shelves them again.