Posts filed under “Books & Literature”

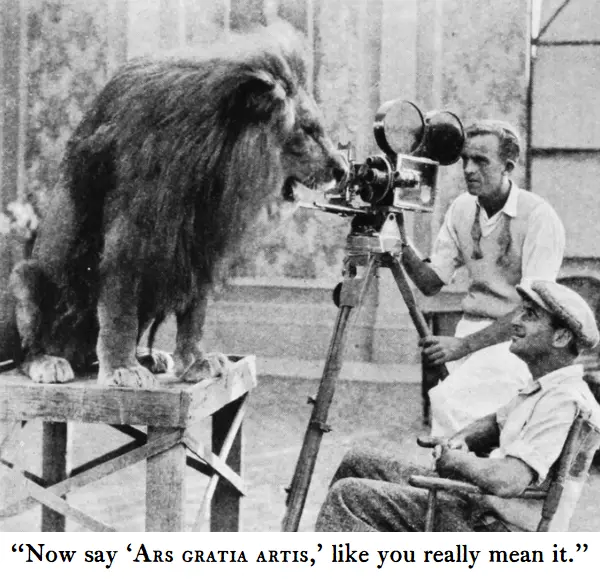

FROM THE ILLUSTRATED EDITION.

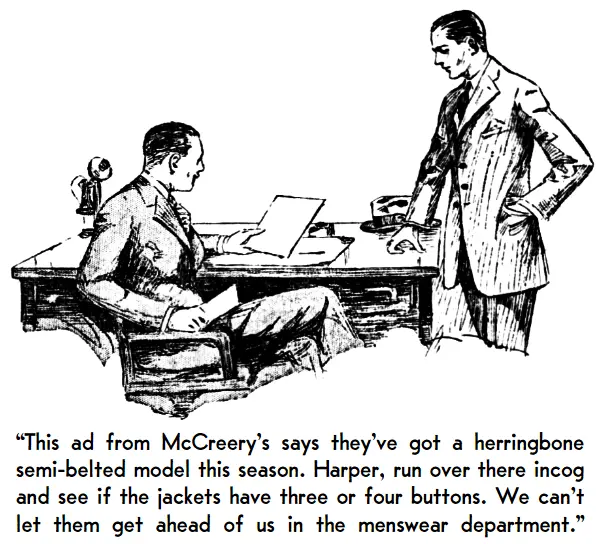

FROM THE ILLUSTRATED EDITION.

WHAT SHOULD WE CALL IT?

It’s an interesting phenomenon in the world of literature, and it seems to Dr. Boli that there ought to be a word for it. What do you call it when the dominant group is treated as the norm, but the non-dominant groups are assigned to their own little ghettos? Ethnicgroupism? Nationaloriginism? There ought to be some short and simple term for it, don’t you think?

LET’S TALK ABOUT SOMETHING INTERESTING FOR A CHANGE.

This is not a new idea to you. You had already been aware of the water when you opened the book. It seems to you that the idea of “water” is contained in the idea of “ocean.”

But surely we must be about to get to the good stuff. You go on to chapter two and find that it describes in minute detail another class of evidence by which we can deduce that the ocean is full of water. The third chapter describes experiments with floating bodies, whose buoyancy proves that there is water in the ocean underneath them. The fourth chapter brings in a hygrometer, whose needle is pegged at the top of the scale when the end is dipped in the ocean. The rest of the chapters consist of stories of historical figures who went bathing in the ocean and came out wet. The concluding chapter summarizes all the evidence, and ends with a ringing declaration that it can no longer be denied that there is water in the ocean.

Well, that book was a disappointment. You didn’t learn anything about the ocean, because the book was only interested in the one thing about the ocean that you already knew.

So you take a class in oceanography at the community college—but once again you find that the professor and the course material have only one thing to tell you, which is that there is water in the ocean, and nobody can deny it.

In desperation, you turn to YouTube—a desperate measure indeed—and find that most of the videos that come up when you search for “ocean” are all about the astonishing and outrageous discovery that there is water in the ocean.

What would you think after all that? You would think that the whole intellectual world had managed to miss the point of oceans. You would think that everyone was belaboring the obvious. You would think that people were depriving themselves of the astonishment and delight they could enjoy if they only looked at the things in the water rather than at the water itself.

We are fortunate that we do not live in that intellectual world. But you probably guessed already (if you are the sort of reader who has the patience for five hundred words of introduction) that we were using the case of the ocean as an analogy for something else.

For most of human history, it was the nearly universal assumption that men and women are different and have different roles. There are still people who believe that today. Dr. Boli is not one of them, and he will explain why very briefly. The assumption was probably useful in paleolithic times, when the sexual dimorphism we inherited from our primate ancestors was a meaningful distinction. In those days it was good that there was one class of big strong oafs who went out to bonk mastodons on the head, and another class of more nimble and thoughtful members of the tribe who made plant fibers into thread and processed the mastodon skins and raised the young and coordinated the meals and established the rudiments of what would later become civilization.

But we might define civilization as the gradual process of making physical differences between human beings irrelevant. A woman can order from Grubhub as easily as a man can. A man can push buttons on the microwave as easily as a woman can. In a world where intellectual capacity is the most important ability, no physical difference between men and women is significant in deciding what position any individual should hold in life.

You may agree or disagree with Dr. Boli’s assertion, and for the purpose of our discussion here it makes no difference at all. We need only agree on the historical fact that, until quite recently, it was almost universally believed that men and women occupied different positions in society. In spite of occasional brilliant cranks who thought otherwise, there was no really serious challenge to that idea until the late eighteenth century at the very earliest.

So when academics look at literature from the past and find evidence of sexism, they are doing exactly what our hypothetical oceanographers did when they presented conclusive evidence that there is water in the ocean. They are telling us what everybody knows, over and over again, ad infinitum and ad nauseam. They are pointing out the water in the ocean.

Yet they do it over and over. Whole academic careers are built on analyzing the literature of the past in terms of patriarchy and the subjugation of women, which is exactly analogous to analyzing the ocean in terms of water. That was the environment in which the people of the past lived. We know that. But there were whales, and angelfish, and sharks, and sea otters, and giant squid, and glorious coral reefs filled with unimaginably colorful life. Wouldn’t it be more fun to talk about those?

Dr. Boli has a proposal for academic literary critics—or art critics, or any other students of the culture of the past. He will stipulate, as they say in the legal business, that the history of the past is a record of the subjugation of women by men. He will even stipulate that the past would probably be improved if we went back and kicked most of those men out of their leadership positions and stuck random women in there instead. The women could hardly do worse. In return, because he has made those stipulations, you do not need to argue your case anymore. Your assertions are admitted. They will not be challenged. Instead, you can start to look at the marvelous things the people who lived in the past did with the world they were given. If you do that, Dr. Boli will probably buy your books.

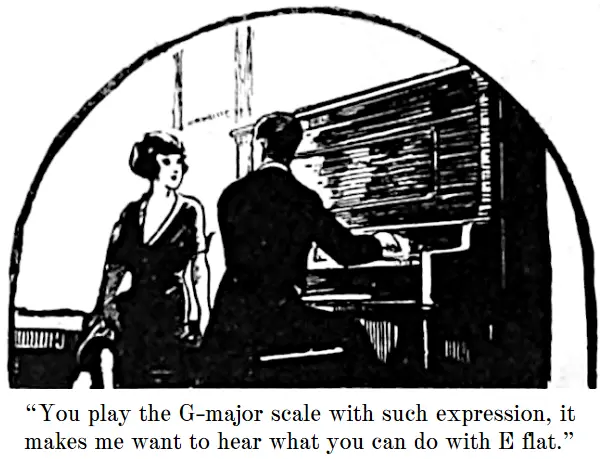

FROM THE ILLUSTRATED EDITION.

From DR. BOLI’S UNABRIDGED DICTIONARY.

Existentialism (noun).—The philosophical position that certain things exist. Not generally taken seriously in philosophical circles.