Posts filed under “Science & Nature”

ASK DR. BOLI.

Dear Dr. Boli: A lot of us here experts have been very concerned about artificial intelligence. These AI companies are training their robot brains on our writing, which took us a whole lot of time to put together and get past peer review, and then they tell people to come to the robot for all their answers. Well, where does that leave us? So, like I said, we’re kind of concerned, and maybe a little hot under the collar about it. But we thought we’d ask you what you thought, because you’re kind of an expert, too, although we had a big argument about what kind of expert you are. —Sincerely, Milfort Quaid, Secretary and Treasurer, Middle American Society of These Here Experts.

Dear Sir: Speaking as the author of the Encyclopedia of Misinformation, Dr. Boli has no objection to AI bots training themselves on his writing.

DR. BOLI’S ALLEGORICAL BESTIARY.

No. 29. The Mosquito.

There are a number of deadly diseases and plagues that would be unable to survive and spread without the aid of the mosquito. Microorganisms by the trillions would perish, and whole species would become extinct.

Nor are microorganisms the only beings that profit from the existence of mosquitoes. On a summer evening, when the sun has gone down in fiery splendor, and billowy clouds are painted salmon and peach all across the sky, and the heady scents of evening blossoms hover in the cooling air, human beings might enter a state of complacent contentment and universal benevolence, were it not for the mosquitoes who irritate them and stir them up to real accomplishments, such as wars and massacres.

Mosquitoes are elegantly constructed creatures, nearly invisible in flight, and having a natural teleportative ability. You can slap at a mosquito, but the mosquito will not be there when the blow lands. The few mosquitoes that do allow themselves to be slapped have usually gorged themselves into suicidal depression.

Allegorically, the mosquito is the patron insect of car alarms, stuck kitchen drawers, construction zones, public-address systems, and other irritants that give civilization its character.

ASK DR. BOLI.

Dear Dr. Boli: I was watching some nutrition expert on YouTube, and I mean he must have been an expert or he wouldn’t have been on YouTube, but he left me confused. He was talking about how Americans’ health problems are caused by “hyperpalatable” foods, but as an example of a “hyperpalatable” food he mentioned Pop-Tarts. Insert question mark in parentheses. So I was thinking that maybe “hyperpalatable” doesn’t mean what I think it means, and I was wondering whether you could explain it. —Sincerely, A Big Fan of Food, but Not Really of Pop-Tarts.

Dear Sir or Madam: To understand what “hyperpalatable” means, you must keep in mind the Mencken dictum that no one ever went broke by underestimating the taste of the American people.

First of all, the word “hyperpalatable” is itself a sin against good taste. It is a middlebrow coinage at home among middlebrow YouTube pundits; it mashes Greek and Latin together, which seldom produces euphonious results. “Superpalatable” would be better and identical in meaning, combining a Latin prefix with a Latin root and suffix; but because “super” is readily understood even by uneducated English-speakers, the middlebrow prefers to say “hyper,” which sounds scientific because it is less usual.

But even if the YouTubist had used the proper term, we are still left with the necessity of explaining why he thought Pop-Tarts were more than usually delicious. The only explanation Dr. Boli can think of is that your YouTube personality was an American consumer.

It is true that an ordinary human being of ordinary tastes, confronted by a choice between Pop-Tarts from the convenience store and paczki from the local bakery, would not pick the Pop-Tarts as the more palatable of the two. But American commerce has bred a community of consumers who do not have ordinary tastes. Many of them have never set foot in a local bakery. Although Pop-Tarts are made by a process originally designed for dog food, they bring together dough and sugar, thus making a first step toward deliciousness.

In Dr. Boli’s opinion, the loose talk about “hyperpalatable” foods is missing what makes these foods ubiquitous and successful. Even the word “superpalatable” would be wrong, for obvious reasons. They are not superpalatable; but they are superconvenient—especially for the peddlers of snacks. It is difficult to make paczki that will survive distribution to local supermarkets for sale even the next day; but it is easy to make foil-packed dehydrated toaster pastries that will sit on a shelf for months or possibly years with no obvious chemical change. For the consumer who trusts only national brands and who buys snacks at a convenience store, the manufactured foods are the ones that are always available; and for many consumers they are the only foods they ever experience.

What is to be done? Dr. Boli is often suspicious of massive government interventions, but there is a war to be won here. The public welfare is at stake. The obvious solution is a government program to make sure that the average citizen is no more than two blocks’ walk from a bakery selling fresh pastries of the most delicious sorts. Will that make Americans healthier? Almost certainly not; in fact, they might die even younger. But they will die praising God, and thus their eternal welfare will be assured.

KILO, MEGA, KIBI, MIBI…

In fact, 12 million pixels is a number with odd mathematical properties in photography. It is very rare for a camera to make pictures with a number of pixels in either dimension that is divisible by a big round number like 1,000; usually the dimensions are something like 4,608 x 3,456. The reason has to do with the aspect ratios of rectangular pictures, which in most cameras are either 3 x 2 or 4 x 3. At an aspect ratio of 4 x 3, 4,000 by 3,000 pixels make up exactly 12 million pixels, which is intellectually satisfying; but you need some math to figure out what figures make up 10 million pixels or 16 million pixels at the same aspect ratio.

So looking for evidence that pixels were counted the way bytes are counted got us nowhere. But our search did lead us into an interesting demonstration of an Internet principle Dr. Boli has pointed out before, to which we may for the sake of convenience assign the name Boli’s Law of Internet Controversy: On the Internet, the victory goes to the most pedantic.

It used to be true that a kilobyte was 1,024 bytes, and a megabyte was 1,024 kilobytes. But the pedants have had their way with “kilobyte” and “megabyte,” insisting that they must be exact powers of ten. Therefore a unit of 1024 bytes is a kibibyte; and similarly, what you think of as a megabyte is a mibibyte. Wiktionary now classifies the usual meaning of “kilobyte” as a secondary “informal” definition; and we can see the moment the pedants invaded, because Wiktionary also preserves the discussions that surround its changes. Three years ago, User A said,

Switch def. 1 and 2 even if right (in the past?)

kilobyte (kB) for 1000 bytes might not be rare anymore? Is it standard in Operating systems now? Many computer hackers want to hang on to KB vs kB, but might be admitting defeat and accepting kB and use KiB (or KB, or Kilobyte with capital K, to distinguish).

Note, incidentally, the punctuation that indicates the use of the interrogative tone in discourse, which Dr. Boli keeps promising to write an essay about in his series on cultural neoteny, and he will probably get around to it eventually. To this indefinitely phrased statement, User B replied:

Absolutely. The binary definition of 1024 is officially deprecated, and not only should the numbers be switched it should be made clear that the binary definition is obsolete.

Now, here is an interesting glimpse into the mind of the pedant. Read that sentence again, and then ask yourself: What office has the authority to deprecate, officially, a common noun in English?

There is an answer to that question in many other languages. If we were speaking French, we might be able to refer to an official ruling of the French Academy on the meaning of “kilobyte.” But English never developed such an authority. We may trace the reason back to Samuel Johnson.

The preface to Johnson’s dictionary is a work that truly deserves to be called seminal, because it sowed the seeds for all the lexicographical thoughts that have sprouted in English since Johnson’s time. It is also one of the finest specimens of English prose ever written.

In this preface, Dr. Johnson explains that he had thought he might set the rules for correct English for all time. But then… Well, let us hear it from the Doctor himself:

Those who have been persuaded to think well of my design, require that it should fix our language, and put a stop to those alterations which time and chance have hitherto been suffered to make in it without opposition. With this consequence I will confess that I flattered myself for a while; but now begin to fear that I have indulged expectation which neither reason nor experience can justify. When we see men grow old and die at a certain time one after another, from century to century, we laugh at the elixir that promises to prolong life to a thousand years; and with equal justice may the lexicographer be derided, who being able to produce no example of a nation that has preserved their words and phrases from mutability, shall imagine that his dictionary can embalm his language, and secure it from corruption and decay, that it is in his power to change sublunary nature, or clear the world at once from folly, vanity, and affectation.

This seems like obvious truth to English-speakers, because we have grown up in a world where Johnson’s opinion is accepted as dogma. Yet it is not dogma for other languages, as Johnson himself points out.

With this hope, however, academies have been instituted, to guard the avenues of their languages, to retain fugitives, and repulse intruders; but their vigilance and activity have hitherto been vain; sounds are too volatile and subtile for legal restraints; to enchain syllables, and to lash the wind, are equally the undertakings of pride, unwilling to measure its desires by its strength.

Johnson’s opinion that language cannot be legislated has become the dogma of professional lexicographers. Merriam-Webster defines kilobyte as “a unit of information equal to 1024 bytes,” and then adds, “also: one thousand bytes.” The American Heritage Dictionary has a very similar definition, with a long usage note at gigabyte explaining that the first meaning is more common in most contexts, but the other more common for certain branches of the industry.

None of this satisfies the pedant, however. The professional lexicographers are wrong. The pedant knows, and his authority is indisputable. It is official. The official authority usually turns out to be a high-school English teacher who taught pedantry along with English, but the pedant has absolute faith in the irrefutability of his knowledge. If you want to know how Sisyphus felt, try starting a discussion on the Wiktionary page for kilobyte, saying, “Hey, I don’t think you’re really right about…” You will not win, because you are not the most pedantic person on the Internet.

Well, then, what have we learned? Nothing about megapixels. As far as Dr. Boli has been able to determine, “megapixel” has always meant a million pixels, not a power of two, and not a little bit less than a million pixels, which is what we would require for 4,000 x 3,000 to make 12.1 megapixels. But we have learned, once again, that the only way to win an argument on the Internet is to be more pedantic than the opposition and never to admit the possibility of error. There was a time when Dr. Boli would have called himself pedantic, but the Internet has taught him that he is underqualified for pedantry.

THE MEGAPIXEL MYSTERY.

So why, Father Pitt asked, is it advertised as a 12.1-megapixel camera? He could not come up with any good answer to that question. Every definition of “megapixel” he found said that it was a million pixels, not a scant million, not a baker’s million, but a plain old honest-to-goodness million. Multiplying 4,000 by 3,000 gives us 12,000,000, according to the old-fashioned math Father Pitt learned.

Yet cameras with a resolution of 4,000 by 3,000 are usually advertised as 12.1-megapixel cameras. It seems to be the industry standard.

So Father Pitt came to us and asked his question, and of course we gave him the verbal equivalent of a shrug and asked why he thought we should know.

But then the question ate at us.

Well, here is a job for artificial intelligence! Surely the bots, having absorbed the wisdom of the entire Internet, would have come across exactly the answer we were looking for and could distill it into a few short paragraphs in the style of a junior-high-school essay.

So we asked Google’s pet bot, “Why is a resolution of 3000 by 4000 called 12.1 megapixels instead of 12.0 megapixels?”

The answer came quickly and included a numbered list. It began, “A 3000×4000 resolution is exactly 12,000,000 pixels (3000 x 4000), which rounds to 12 megapixels (MP), but…”

Hold on there, Googlebot! You say 12,000,000 pixels rounds to 12 megapixels, but by Dr. Boli’s calculation it is exactly 12 megapixels. This is the anomaly for which we sought an explanation. You are indulging in a petitio principii, or in plain English begging the question.

At any rate, the bot tells us some things that are of little use, the only possibly relevant observation being that sensors don’t necessarily have exactly the stated number of pixels, so there might be slightly more than 12,000,000 pixels in the sensor—which may be true, but not in any way useful if the images that come out are exactly 12,000,000 pixels.

“In summary,” the bot concludes, “your 3000×4000 image is exactly 12MP, but cameras often have sensors with slightly different dimensions or use marketing-friendly rounded numbers, so 12.1MP is just a slightly more detailed label for what’s essentially a 12-megapixel sensor/image.”

It sounds as though the bot has come up with a very polite way of saying, “Your image is exactly 12 megapixels, but marketers lie.”

However, it occurred to Dr. Boli that there are many professionals of different sorts among his readers, and perhaps some of them might know why a camera that produces images with 12,000,000 pixels is sold as a 12.1-megapixel camera. Is there any good answer? Or do we have to settle for “marketers lie” and sadly shake our heads at the state of the world we live in?

DR. BOLI’S ALLEGORICAL BESTIARY.

No. 28. The Road-Runner.

Appropriately enough, the road-runner allegorically represents the virtue of patience.

ASK DR. BOLI.

Dear Dr. Boli: Pit bulls have become a very popular dog breed lately, and I usually see them just as housepets. But they have a peculiar shape that makes me think they were bred for some practical employment. The name “pit” suggests something to do with the stock market, but I couldn’t find any confirmation of that speculation. What was the original purpose for which pit bulls were bred? —Sincerely, Bancroft E. FitzWallaby, President, Mid-Atlantic Association of Idle Speculators.

Dear Sir: You will find all sorts of incorrect assertions about the origin of pit bulls, usually based on folk etymology and presented as fact. The truth, however, is simple, and not hard to deduce from the form of the animal, which you correctly guessed was dictated by practical utility. Pit bulls were bred to be dishwasher-preparation dogs in the “dish pit” of busy mess halls, dining halls, restaurants, and other eating establishments. They are the product of generations of selective breeding with the aim of producing a dog whose tongue is broad and agile enough to sweep a plate clean in two licks. Furthermore, many of the pit bulls you supposed were simply housepets are in fact productively employed in their families at the work for which their ancestry has fitted them.

ASK DR. BOLI.

Dear Dr. Boli: Everywhere I look, I keep reading about the dangers of “blue light” from computer monitors, phone screens, and televisions. What’s so bad about blue light? —Sincerely, A Man Who’s Colorblind Anyway.

Dear Sir: Public-health experts worry that, if you are constantly exposed to blue light, you will become a Blue Light Special. And look what happened to Kmart.

ASK DR. BOLI.

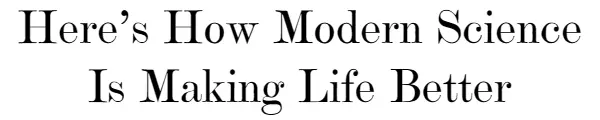

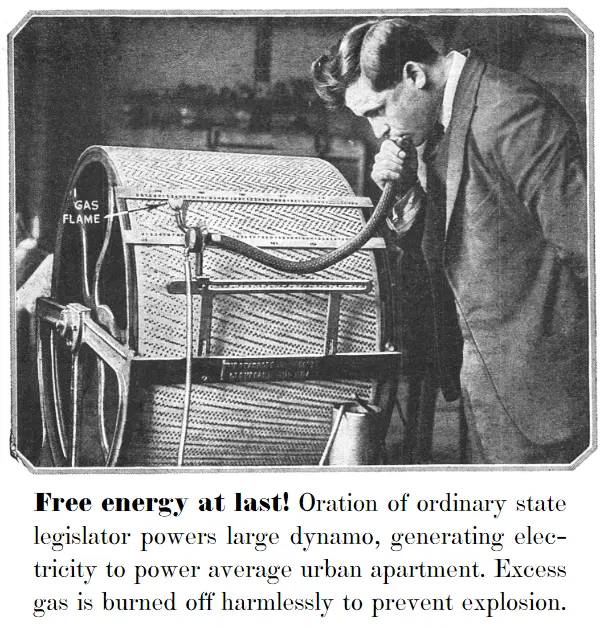

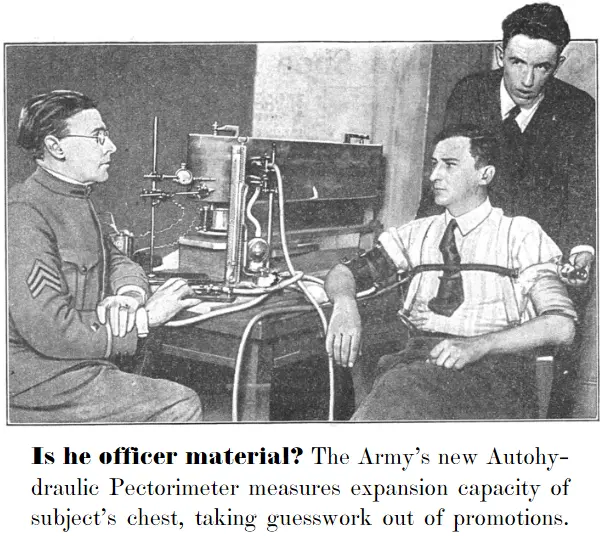

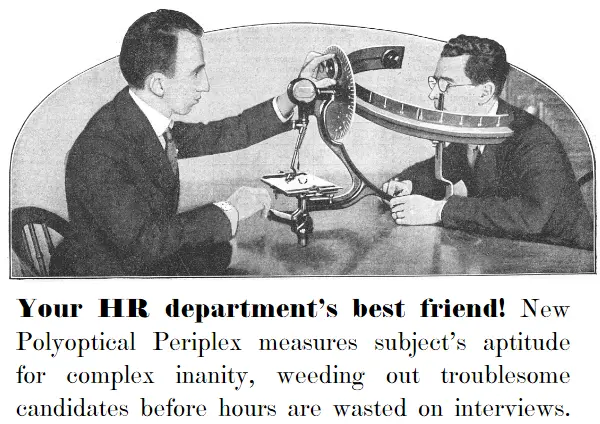

This image does not have a caption yet. It will be published with the correct caption as soon as a thorough search of the Akashic Records has been made.

The research methodology is probably not as arcane as our correspondent thinks it is. Every once in a while, it is an amusing pastime to look through the recent additions to the scanned publications in the Internet Archive—filtering out anything published later than 95 years ago. Any magazine opened at random will probably provide a few illustrations. They must be cleaned up and dressed in their Sunday best to be published here, but that is what the GIMP is for.

As for the explicatory text, that is a more complex endeavor. Many of the captions under these images are entirely incorrect as they are found, but the correct versions can be discovered by the methods explained more than a century ago by Dr. Rudolf Steiner. He tells us that “at a certain high stage of knowledge, man can even penetrate to the everlasting sources that underlie the passing things of time.… Those who have learnt to read such a living script can look back into a far more distant past than that which external history depicts—and they can also, by direct spiritual perception, describe those matters which history relates, in a far more trustworthy manner than is possible by the latter.” This is called reading the Akashic Records, and, as Dr. Steiner patiently elucidates, it is completely different from making stuff up.

HOW MODERN SCIENCE IS MAKING LIFE BETTER.