Posts filed under “Science & Nature”

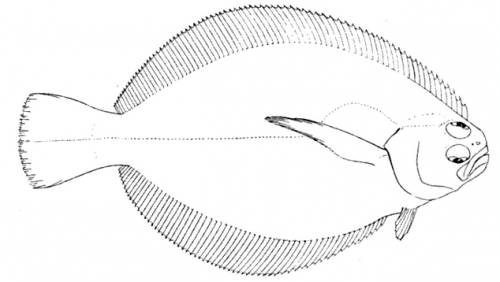

ASK HERBERT THE PSYCHIC FLOUNDER.

Dear Mr. Flounder: I need to get groceries tomorrow, and I was wondering: Is this a good week for watermelons? —Sincerely, Shopper.

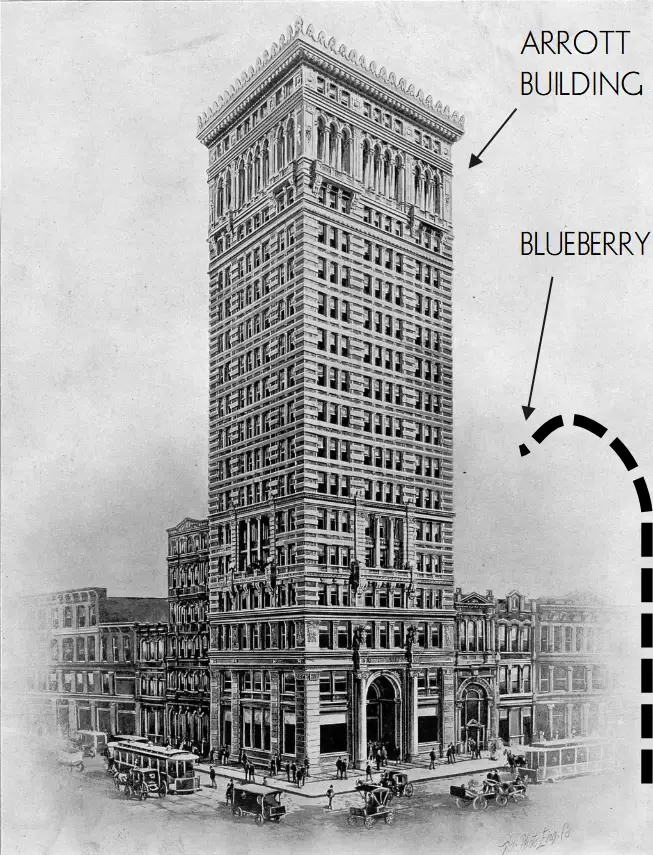

Dear Shopper: While skating along the astral plane this afternoon, I had a vision that went something like this. There were two lampposts, an Irish one and an Italian one, and the Italian lamppost said, “I say, old man, my dog has no nose!” And the Irish lamppost said, “Indeed? But how does he smell?” But by this time the Italian lamppost had turned into a hygrometer the size of the Koppers Building, and because it was so tall it did not hear the reply of the puny Irish lamppost, which remained a lamppost. And then a stag with blue antlers trotted between them and said, “I know something you don’t know,” and then it went down into the subway and caught a Silver Line car headed for Library, but it got off at Washington Junction. I believe this means you should avoid watermelons this week.

From DR. BOLI’S ENCYCLOPEDIA OF MISINFORMATION.

DIRE PREDICTIONS No. 11.

DIRE PREDICTIONS No. 9.

From DR. BOLI’S ENCYCLOPEDIA OF MISINFORMATION.

Helium.—If you inhale helium and then speak, your voice sounds comically high-pitched because sound travels faster in a gas that is less dense than atmospheric air. This means that, if you speak long enough, you will hear words you have not spoken yet. Try it sometime!

USEFUL NUTRITION HINTS.

A diet rich in rusty nails will remedy most iron deficiencies. Be sure you are up to date on your tetanus shots.

Yogurt will prolong life indefinitely. If you know any people who have died, it is because they forgot to eat their yogurt.

Swedish rye crispbread is high in fiber. We can say that much for it, anyway.

Beans have no nutritional value until they are doused in brown sugar.

Ask your grocer whether kale is right for you. In some states it is available without a prescription.

Granola can be made into a complete source of protein by adding it to ice cream.

HELPFUL GARDENING HINTS.

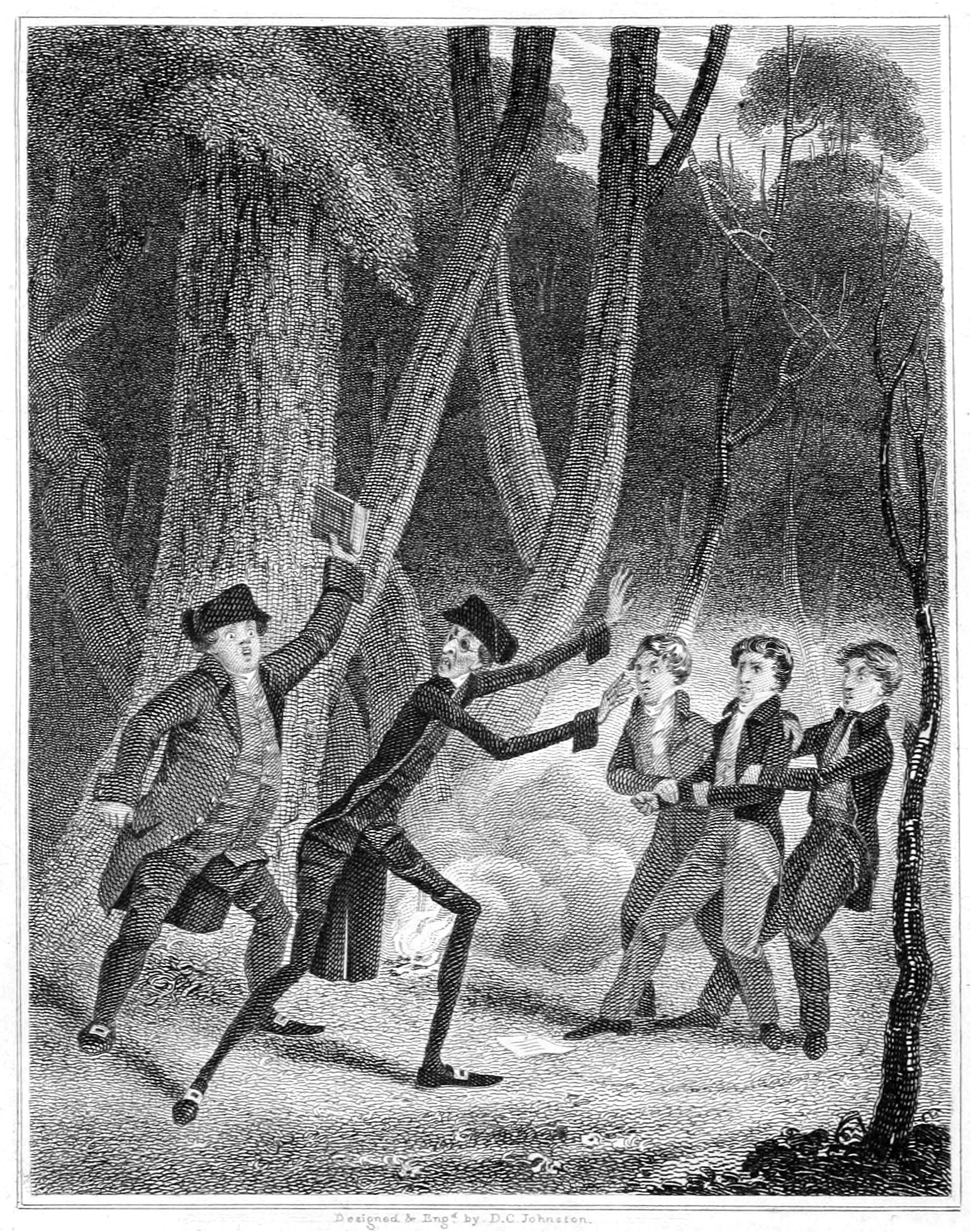

When planning an orchard, make sure to plant your apple trees where their branches will overhang eminent natural philosophers.

Growing spinach directly in the can is a real time-saver.

If your tomatoes become overripe, they can often be sold at a handsome profit wherever bad opera singers are performing.

With sufficient motivation, sweet corn can be genetically modified to look and taste exactly like rhubarb.

Rutabagas are hard to spell. Try planting turnips instead.

Dandelions have an astonishing number of culinary and medicinal uses, and a canny recognition of their virtues may absolve you from the necessity of planting a garden altogether.

ASK DR. BOLI.

Dear Dr. Boli: I bought some organic whole flax seeds at the grocery store yesterday, because the last time I bought flax seeds they were made of aluminum, and they were too crunchy. So I got the package home, and I noticed it said this on the back:

Each of our Simply Nature products is free from over 125 artificial ingredients and preservatives.

I can’t stop thinking about this. I thought I understood math, but this just blows everything I thought I knew out the window. How do they count the ingredients that aren’t there? This has been driving me nutso. I’m thinking of throwing away the bag, because every time I look at it my brain spins in loops. Please help me, or call Western Psych and tell them it’s an emergency. —Sincerely, A Woman Who Wonders Why She Needed Flax Seeds in the First Place.

Dear Madam: You have no need to worry. The fundamental laws of mathematics are still operative, but so are the fundamental laws of marketing. You will note that the marketers have employed one of the most useful terms in marketing, namely the word over.

The word over has many uses. One of the most common is to say, “Here comes a number.” But another common use is to protect the consumer from numbers too large for her comprehension.

Marketers are keen students of psychology. They know that the human imagination is limited when it comes to quantities and magnitudes. Numbers in the dozens strike us as large. But we cannot imagine very large numbers. Thousand, million, billion—those are all the same to the human imaginative faculty, and they are all meaningless. It is not known exactly where the line is between large and meaninglessly huge, but current marketing research indicates that it is probably somewhere a little below 150.

Now, obviously, there are many more than 125 potential artificial ingredients—that is, substances that can be produced by chemists in a laboratory and added to food products without immediately killing the consumers thereof. But 125 hits your imagination as a large number, whereas an actual count of currently available artificial ingredients would simply wash over you as an incomprehensible parade of digits. Therefore, by saying “over 125,” the marketer engages your imagination and allows it to picture a large number of ingredients that are not present in your flax seeds.

We hope this explanation obviates the need for a call to the Western Psychiatric Institute.

HOW DR. BOLI WILL SAVE SCIENCE.

We ask because the usual mechanism for distributing scientific information is so obviously broken that it is difficult to see how scientific knowledge can ever be communicated at all.

But before you put on your funereal black and mourn the death of science, allow Dr. Boli to anticipate the end of this article and assure you that science is very much alive, and it is because the native intelligence of our scientists has successfully adapted to what would, to the ignorant layperson, seem a catastrophe from which science could never recover. Furthermore, Dr. Boli will propose to refine that adaptation in a manner that will be profitable both to the scientific establishment and to himself. The profits to himself will be financial; the profits to the scientific establishment will be of a more intangible nature.

If you have any interest in scientific research, a few minutes spent at a site called Retraction Watch will be informative. We often see big headlines about scientific studies, but journalists seldom even notice if a study they reported is later retracted because, for example, its authors discovered that samples had been contaminated, or calculations had been incorrect. Those things happen, and authors who ask for their own papers to be retracted are heroes of science. We need more of them.

A much larger percentage of papers, however, are retracted because of fraud. Some of it is subtle fraud: a researcher tried to fake data, and would have got away with it if it hadn’t been for those meddling kids and their Internet connections. But some of the fraud is not subtle at all. Here is a typical article in Retraction Watch: “Springer Nature geosciences journal retracts 44 articles filled with gibberish.” (The number appears to have risen to 62 after the article was published.) The article explains that the retracted articles “from their titles appear to be utter gibberish—yet managed still to pass through Springer Nature’s production system without notice.”

Is it fair to judge scientific articles just by their titles? After all, many scientific disciplines lean heavily on esoteric jargon. Many of the species descriptions in Gray’s Manual are gibberish to anyone not initiated into the mysteries of botanical terminology.

Well, here is the list of retracted articles (in PDF form), and you can judge for yourself. We quote a few titles:

Evaluation of mangrove wetland potential based on convolutional neural network and development of film and television cultural creative industry

Distribution of earthquake activity in mountain area based on big data and teaching of landscape design

Distribution of earthquake activity in mountain area based on embedded system and physical fitness detection of basketball

Plant slope reconstruction in plain area based on multi-core ARM and music teaching satisfaction

All right, so it is probably fair to judge from the titles.

This is an entire special issue of a scientific journal, filled from beginning to end with random computer-generated rubbish. Nor do we have the consolation of saying to ourselves, “Well, we don’t rely on little fly-by-night publishers for our scientific information.” This one was published by Springer Nature, publishers of Nature and Scientific American, among other things you might have heard of. Springer Nature reported a revenue of € 1.7 billion in 2021.

How did it happen? Well, it appears that a well-known academic’s email was hacked, and the hackers sent Springer Nature an email saying, “Hey, how would you like a special issue of the Arabian Journal of Geosciences devoted to important research about the connection between rainfall runoff and aerobics training? I’ve rounded up some distinguished geoscientists to contribute.” And the publishers said, “Sure, whatever, you’re editor, just make sure the authors all pay their fees on time.”

There’s the problem. No one has ever come up with a good way to fund the publication of scientific research. It was not a very big problem when scientific journals were run by people who were mostly interested in the science, and were simply delighted if they could make enough money to pay themselves an editorial salary. But now scientific journals are run by business-school graduates who are exclusively interested in money. For some time they tried to make that money by squeezing outrageous subscription and per-article fees out of academic libraries and well-funded researchers, but that eventually provoked a backlash, and researchers who couldn’t afford to do research started demanding open access. But who will pay for that? If readers won’t pay, obviously authors will have to. So that is, more and more, what academic journals do these days. In the old days, when money came from subscriptions, the motivation was to sell as many subscriptions as possible, and the most efficient way to make money was to print as few very-high-quality articles as you could get away with, so that production costs were low but subscribers couldn’t do without your journal. Now, with authors paying and access open to all and sundry, the obvious motivation is to publish as many articles as possible, and the only motivation for maintaining quality is the worry that authors might not pay quite as much to be published in the same journal as “Characteristics of heavy metal pollutants in groundwater based on fuzzy decision making and the effect of aerobic exercise on teenagers” (another of the retracted articles from the Arabian Journal of Geosciences).

Why would authors pay to be published? To a professional writer, it seems obviously backwards. The money is going the wrong way. But these are not professional writers: they are academics whose careers depend on publications.

Suppose, however, you are an academic, but you are not a very good one, and you never produce any research worth publishing. You still want a career. What to do? Simply answer one of the many on-line advertisements offering authorships for sale, and soon your name is on an article in the prestigious Arabian Journal of Geosciences, published by Springer Nature.

Hacking academic editors’ emails is a popular scam and has succeeded more than once. Here is an article called “Scammers impersonate guest editors to get sham papers published,” which appeared in Nature, of all places. It cites reporting from Retraction Watch. (The article is behind a paywall; Dr. Boli has access through the Boli Institute, and your local library may offer free access for library-card holders.)

But there are other good scams out there, some of them even easier. If a journal folds, its Web domain may be up for grabs. Then you can set up a fake journal that looks like the dead one and take over the original journal’s reputation and indexing in standard academic databases. Here is a spreadsheet of hijacked journals that, as of this writing, contains 207 entries. And we have by no means exhausted the ways to get fake science published and accepted as a legitimate publication.

This is very bad news. Yet science continues, and continues to produce some spectacular results. How can that be?

Science continues because working scientists have known for a long time that there is a distinction between papers published to advance science and papers published to advance the authors’ careers. No matter where the papers are published, working scientists develop an instinct for recognizing the useful science and separating it from the garbage. But because universities these days are run by business-school graduates rather than academics, it is possible for shady academics to advance their careers by publishing work that everyone in their discipline knows to be worthless, but that looks like a paper to an MBA.

This is where Dr. Boli makes the proposition he promised earlier, the one that will be equally profitable to the scientific world and to himself.

What academics need is a respectable journal to publish their work, even if it is complete nonsense, so that the MBAs who control their careers can see that they have a strong publication record. What the scientific world needs is for such publications to be segregated from the journals scientists need to read to stay informed in their disciplines.

Therefore, Dr. Boli is announcing the Atlantic Journal of Noninformational Research, which will be open to all disciplines, and will publish any article whose author can fork over the $3500 fee for publication. All articles will be peer-reviewed, which is to say that they will be reviewed by Dr. Boli, who counts as a peer because he believes he is at least as good as any of you. All articles will pass peer review.

Furthermore, it is well known that publication is only half the battle. To rise higher in the academic hierarchy, authors must have their articles cited. Therefore Dr. Boli is establishing a second journal, the North American Journal of Citations, to serve the needs of undercited academics by citing the articles in the first journal, for an additional $3500.

You can see how this solves both problems at once. The journals will be attractively formatted to professional standards calculated to convince any MBA that real publication has occurred. Practicing scientists will never have to crack their covers, and will thus be spared the effort of sifting through the rubbish to find the diamonds of information.

Finally, Dr. Boli is prepared to make a very generous offer to the managers of Springer Nature. He will accept a salary of $500,000 a year to be the Springer Nature Gibberish Gateway. It is obvious that the company needs someone to take that position, and the price is cheap. If a single human being at Springer Nature had looked at that issue of the Arabian Journal of Geosciences for one minute before it was turned loose on the world, this embarrassment would never have happened.

And that is what Dr. Boli proposes to do. The last stage in every publication issuing from Springer Nature will be to send it to Dr. Boli, who will look at it for one minute and flag it for review by a competent expert if it appears to be utter gibberish. Let us say that Springer Nature puts out three thousand journals a year; this means that Dr. Boli will be devoting about ten minutes a day to the task, with Sundays off, which he does not consider an excessive amount of time.

The figure $500,000 has been chosen with some care. It is probably less than the cost of one mass retraction, counting the blow to the company’s prestige, so the publishers will be saving a great deal of money overall; but at the same time it is a large enough amount to inspire confidence, because shady academic charlatans are unlikely to be able to offer a sufficiently compromising bribe. Otherwise, of course, Dr. Boli would have been willing to do the work gratis, merely for love of Science; but he recognizes the value of confidence. Specifically, it is worth half a million dollars.