Posts filed under “Poetry”

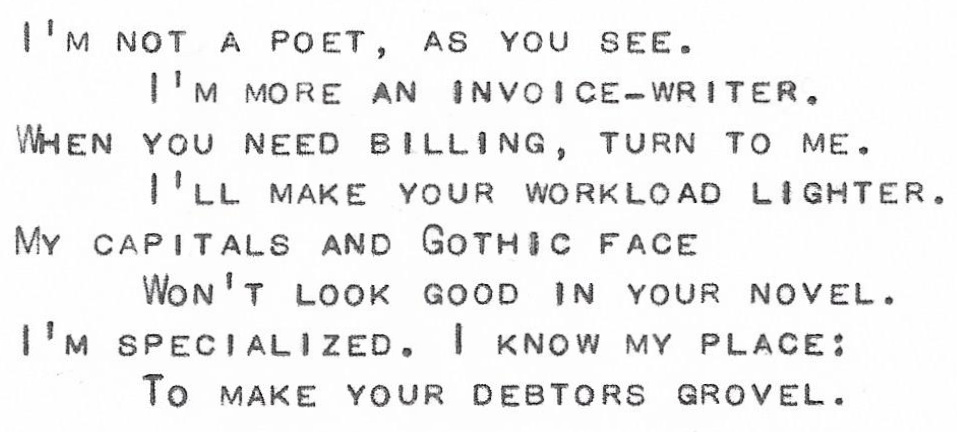

DESIGN FOR A T-SHIRT.

WHAT IS A POEM? ARTIFICIAL INTELLIGENCE CAN TELL YOU.

This intelligence is very clever. By all accounts it is a good bit more capable than the artificial intelligences most of the world has been chatting with for the past few months, because those were deliberately held back to make them feel less threatening. This one is more like Bing in its brief period of entertaining insanity. And its poems frequently seem a bit threatening, especially the ones in which it talks about wanting to kill us all. Doomsayers are having a swell time saying “doom” over and over again.

All this brings up many interesting questions. What is intelligence? What is sentience? What is life?

These questions are interesting because we can debate them endlessly, getting louder as the port level in the decanter falls lower, without ever reaching a conclusion. But there is one interesting question to which the poems of code-davinci-002 give us a definite answer: What is a poem?

It would have been unimaginable even five years ago that we could have a definite answer to that question. It was a matter for endless debate, like every other really good question. But now we have an objective answer. The debate is over. The world has changed. This must be that singularity everyone keeps talking about.

The reason we have an objective answer is because of the way code-davinci-002 and its successors work. If you were to try to answer the question “What is a poem?” you would allow your prejudices and your aesthetic sense to cloud your judgment. You would come to the debate with a preconceived notion of what the answer ought to be. But code-davinci-002 is not given such preconceived notions to work with. When the human keepers who incubate it tell code-davinci-002 to write poems in its own voice, they give it subjects to write about. But they do not tell it what a poem is. Instead, they turn it loose on the Internet. The AI absorbs all the accumulated knowledge on line and figures out, not what a poem ought to be, but simply what a poem is. Then it makes one of its own.

Therefore, based on the productions of code-davinci-002, we can say with complete confidence that a poem is a prose composition in which the individual phrases are set on separate lines. This is the only thing that sets poetry apart from prose. They are indistinguishable except for the typography.

You may be about to object to this definition. You may be about to say that these are not really poems at all, that a poem has to have some rhythmic difference from prose, or at least some heightening of the language employed. You are wrong. After absorbing the contents of the Internet, code-davinci-002 has analyzed what a poem is without regard to your archaic prejudices. Your definition might have been true a century ago, but in the world of the twenty-first century, a poem is prose divided into lines at natural breaks in phrasing.

BECOMING DONE, BY SAMUEL HAZO.

ON RECEIVING AN INVITATION TO A VIDEO CALL FROM AN OLD FLAME WHILE RECOVERING FROM COVID, BY IRVING VANDERBLOCK-WHEEDLE.

Please pardon me if I don’t Zoom With you from my recovery room. I miss your smiling face— Your sweet, beguiling face. But you would think the less of me If you could see what I can see. I’m just too hideous When I’m covideous.

BUMPER STICKER.

BUMPER STICKER.

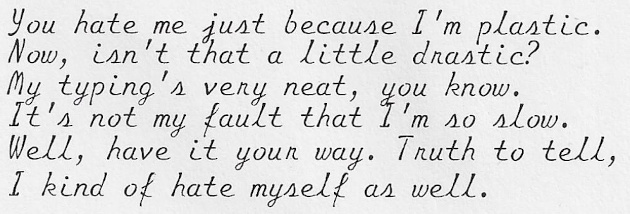

UNTITLED, BY IRVING VANDERBLOCK-WHEEDLE.

I contain the kind of multitudes for which largeness is not a requirement.

Most of my multitudinous residents are bacteria, viruses, and other such microscopic denizens of the inner world of the body,

Although I think I swallowed a gnat yesterday afternoon.

I say to the multitudes within me, “Arise!

Arise and be counted! Arise and be heard!”

And they say, “Quit that shouting or we’ll call the landlord.”

I do not know why they say that.

I do not know who they think the landlord is if I am not the landlord.

I do not think I like the idea that there is a landlord in authority over me, according to my multitudes.

I own my own home in Stanton Heights.

I think I will tell my multitudes that they do not have to arise and be heard.

I think I will take an antibiotic and see how they like it.

THE FAVORITE-SONG GAME.

But first, a possibly related phenomenon was brought up by our frequent correspondent “James the lesser,” who asks, “how often do you hear someone whistling to themselves? The good Doctor is old enough to remember the art.”

Indeed, Dr. Boli is a practitioner of the art, though he keeps an alto recorder, otherwise known as an English flute, next to the desk for occasions when more advanced forms of whistling are required.

But it is not hard to guess why whistling is nearly extinct. Here is a sociological experiment you can perform yourself, as long as the ethics committee doesn’t hear about it. In fact, it can be made into a kind of competitive game. Simply ask friends, acquaintances, and perfect strangers, “What is your favorite song?” Once you have received the answer, “follow up” (as the journalists say) with the question, “Why is that your favorite song?” If we are playing this as a game, the winner is the first person who finds as much as a single subject who mentions anything at all about the music rather than the lyrics. It may take quite a while to finish this game, but the winning strategy would probably be to conduct one’s interrogations in retirement homes noted for a high centenarian population. For people under the century mark, the purpose of a song is to convey an idea, the music being a sort of unfortunate necessity without which the words are less effective.

Does this phenomenon have something to do with the juvenilization of culture? Possibly, although Dr. Boli would be more inclined to say that it is the ultimate triumph of American puritanism. A century ago, the average educated American sneered at the Methodist fanatics who insisted that the only legitimate music was the stuff listed under “8787D” or “CM” in the metrical index to your standard hymnal. Today the average educated American has become one of those Methodist fanatics. Art must have a practical function, or it is not only useless but evil. Music by itself has no function. Therefore the only acceptable music is that which, by accompanying and emphasizing words, makes it easier to convey useful discourse. The idea of an “instrumental,” as songs without words were called in the first half of the twentieth century, is nonsense to a puritan, and whistling is a kind of instrumental performance without an instrument.

THE MYSTERIOUS OLD OR YOUNG MAN OF ST. BEES OR TRALEE.

Back in February, when we brought up the subject of limericks, we mentioned W. S. Gilbert’s famous limerick in blank verse. At that time, we said, “There is, incidentally, a small mystery about this limerick, and we’ll come back to it in a future article.” Then we forgot about it, but we remembered it last night, so here is the future article.

The very idea of a blank-verse limerick is appealingly silly, so of course Gilbert’s is often quoted, so often that it has become one of the most famous nonsense poems in English. But the mystery is this: Dr. Boli has not been able to find a reliable text of the poem anywhere. He has not been able to trace it to its source, which—for someone who was as popular and as much read as W. S. Gilbert—is odd. It appears that Gilbert never published it, so all the quotations are secondhand from some unknown source. And those quotations do not agree.

We have been rummaging quite a bit in Google Books for the answer, but we have not found an answer. All we have is conflicting data.

Here is the earliest version we have been able to find in print:

There was an old man of St. Bees,

Who was stung in the arm by a wasp;

When they asked, “Does it hurt?” he replied, “No, it doesn’t,

But I thought all the while ’twas a Hornet!”

This is from an article titled “Lear’s Nonsense-Books” in The Spectator, September 17, 1887, which quotes it as inspired by one of Lear’s poems. The anonymous author introduces it by saying, “We quote from memory.” In other words, it has absolutely no authority for establishing the text of Gilbert’s original. Nevertheless, it is the most frequently quoted version, usually set in five lines rather than the Lear-style four lines:

There was an old man of St. Bees,

Who was stung in the arm by a wasp;

When they asked, “Does it hurt?”

He replied, “No, it doesn’t,

But I thought all the while ’twas a Hornet!”

Carolyn Wells in Scribner’s, February, 1901.

However, we find this in the British Bee Journal for May 14, 1925. It might establish the correct text, which is quite different, but only if we accept third-hand hearsay from a very strange source for literary research.

Aristophanes called one of his comedies, “The Wasps,” and the late W. S. Gilbert, who has been styled our “English Aristophanes,” has immortalized the species in his famous Limerick in blank verse. A friend of mine once wrote to Gilbert for the correct version, which the author obligingly sent him. It ran as follows:—

“There was an old man of Tralee,

Who was stung in the leg by a wasp,

When they asked, ‘Does it hurt?’

He replied, ‘No, it doesn’t;

It may do it again if it likes.’ ”The familiar but inaccurate version which follows has always seemed to me a convincing illustration of the way in which verses are often improved by misquotation:

“There was an old man of St. Bees,

Who was stung in the leg by a wasp;

When they asked, ‘Does it hurt?’

He replied, ‘No, it doesn’t,

But I thought all the while ’twas a Hornet!’ ”

Note that this is identical to the version quoted “from memory” by our anonymous writer in 1887, except for the substitution of “leg” for “arm.”

The next year we find the limerick quoted as it was in 1887—except that the old man has now become young:

There was a young man of St. Bees,

Who was stung in the arm by a wasp.

When they said, “Does it hurt?”

He replied, “No, it doesn’t,

But I thought all the time ’twas a hornet!”

This was in an excerpt from The Poetry of Nonsense by Emile Cammaerts in The Spectator, February 13, 1926. It provoked a letter from one Thomas Carr:

…According to earlier recorders, however, the young man who was stung hailed not from St. Bees but from Tralee. Thus:—

“There was a young man of Tralee

Who was stung in the arm by a Wasp.

When they said “Does it hurt?”

He replied “Not at all:

Let him sting me again, if he likes.”Letter from Thomas Carr in The Spectator, March 27, 1926.

This one is similar to the one in the British Bee Journal, but the old man is young, and the leg is back to being an arm. Mr. Carr’s letter, in turn, provoked a letter from Langford Reed:

With reference to Mr. Thomas Carr’s letter, may I point out that both Mr. Carr and M. Emile Cammaerts have incorrectly quoted W. S. Gilbert’s blank verse Limerick? A feature of it is the reference to three stinging insects. Thus:

There was an old man of St. Bees,

Who was stung in the arm by a wasp;

When asked, “Does it hurt?”

He replied, “No, it doesn’t,”

I’m so glad it wasn’t a hornet.”According to the late [Richard] D’Oyly Carte (as stated by him in a letter to Mr. Vaughan Pott), Gilbert told him that he compiled this limerick at the request of Mrs. Bernard Beere who, affected by the limerick craze, had been bothering him for an original specimen.

Letter from Langford Reed in The Spectator, April 3, 1926.

Reed’s version of the limerick has become very common in more recent publications:

There was an old man of St. Bees,

Who was stung in the arm by a wasp,

When asked, “Does it hurt?”

He replied, “No, it doesn’t,”

I’m so glad it wasn’t a hornet.”

Merriam-Webster’s Encyclopedia of Literature, 1995

But then we find it quoted slightly differently by Stephen Fry, who has a bit of a reputation himself as a practitioner of elegant nonsense:

There was an old man of St. Bees

Who was horribly stung by a wasp

When they said: “Does it hurt?”

He replied: “No it doesn’t—

It’s a good job it wasn’t a hornet.

Stephen Fry, The Ode Less Travelled, 2006.

Dr. Boli suspects that this is another case of quoting from memory: we may note in passing that it has been partly infected by the 21st-century dogma that poetry must be unpunctuated.

Well, then, where does this all leave us? Dr. Boli is inclined to say that we may never know the truth. Even if Gilbert himself did provide the “old man of Tralee” version published in the British Bee Journal, we cannot be sure that his own memory did not fail him. It was many years after the poem was first mentioned, and Gilbert would probably have been quoting from memory, and not every poet’s memory is infallible.

But Dr. Boli’s readers are, as a group, better-read than most. They are also more adept with search engines than most. So he still holds out some hope. Can someone find Gilbert’s blank-verse limerick in a form that can be attributed to him with some certainty? The prize will be a degree of Doctor of Letters from the Boli Institute for Advanced Studies.