Posts by Dr. Boli

Advertisement.

THE PARLORMAID, THE BUTLER, AND FINNEGANS WAKE.

“Pardon the intrusion, sir,” she said, “but the parlormaid requested guidance which one was unable to give her without consultation. She reports that she found a copy of Finnegans Wake next to the large aspidistra on the side table, rather than on the floor as usual. At first she assumed it had been tossed there, but on closer inspection it seemed to have been placed rather than tossed. She asked whether she ought to recycle it, as usual, or whether sir had some other destiny in mind for it.”

“She is an intelligent young lady,” we replied, “and she was quite correct to ask for guidance. Sir did indeed place the book there, because sir has finally, after eighty-six years of desultory attempts, read every blessed word of Finnegans Wake.”

“Then is it sir’s desire that the book should be recycled?”

“No,” we said quite definitely. “It is sir’s desire that it should be taken to a reputable service and bronzed.”

ASK DR. BOLI.

Dear Dr. Boli: Pit bulls have become a very popular dog breed lately, and I usually see them just as housepets. But they have a peculiar shape that makes me think they were bred for some practical employment. The name “pit” suggests something to do with the stock market, but I couldn’t find any confirmation of that speculation. What was the original purpose for which pit bulls were bred? —Sincerely, Bancroft E. FitzWallaby, President, Mid-Atlantic Association of Idle Speculators.

Dear Sir: You will find all sorts of incorrect assertions about the origin of pit bulls, usually based on folk etymology and presented as fact. The truth, however, is simple, and not hard to deduce from the form of the animal, which you correctly guessed was dictated by practical utility. Pit bulls were bred to be dishwasher-preparation dogs in the “dish pit” of busy mess halls, dining halls, restaurants, and other eating establishments. They are the product of generations of selective breeding with the aim of producing a dog whose tongue is broad and agile enough to sweep a plate clean in two licks. Furthermore, many of the pit bulls you supposed were simply housepets are in fact productively employed in their families at the work for which their ancestry has fitted them.

ON THIS DAY IN HISTORY.

Advertisement.

FROM THE ILLUSTRATED EDITION.

From DR. BOLI’S CULINARY DICTIONARY.

Ba-wan.—Taiwanese pierogies.

Gyoza.—Japanese pierogies.

Kreplach.—Ashkenazi Jewish pierogies.

Mandu.—Korean pierogies.

Maultaschen.—German pierogies.

Momo.—Tibetan and Nepalese pierogies.

Pelmeni.—Russian pierogies.

Pupusas.—Salvadoran pierogies.

Samosas.—Indian pierogies.

Sambusas.—Ethiopian pierogies.

Wonton.—Chinese pierogies.

Pierogies.—Polish ravioli.

Advertisement.

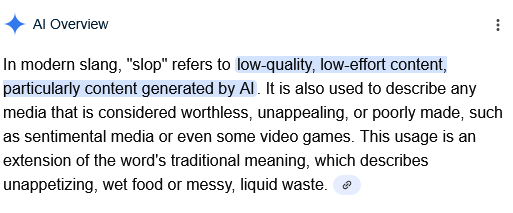

WHAT IS SLOP?

Γνῶθι σεαυτόν, as the graffiti said on the Temple of Apollo at Delphi. This is, as the young people say, very meta.

The screenshot extract from Google results is quoted for the purpose of mockery, which is one of the purposes that qualify as “fair use” in American legal theory.

IS ARTIFICIAL INTELLIGENCE STEALING YOUR STUFF?

Pardon us, please. We have been reading too much James Joyce.

Let us begin again (Finnegan!).

Our article about whether there can be AI art provoked an interesting debate. Fred wrote:

The way it’s set up AI generates “art” without the permission of about eight billion involuntary contributors which I would think would be a violation of copyright. The copyright office might not think so but I suspect it will take approximately 150 years before the question is really settled.

In response, Belfry Bat wrote that

up until some remarkably recent point, ’most every artist anywhere spent most of his apprenticeship (oh, how I date my assumptions!) consuming, analyzing, synthesizing the art of Tradition; and “breaking” his hands, as it were—to make them do what he rather than they themselves wanted—by “copying” or “studying” these historical ARTifacts.

He goes on to doubt the possibility of complete originality in art, describing it as “a very young myth.”

In the case of human artists, it seems true beyond argument that every artist has learned from previous artists and is influenced by artists of the current generation, willingly or unwillingly. Even the self-trained outsider artists who are occasionally discovered by the art world, like John Kane, can usually be dated just by their style, showing that they were part of a larger environment of artists who, consciously or unconsciously, learned from each other’s art. There is nothing wrong with that, and in fact it is the very definition of culture. Dr. Boli was about to say that a society without those influences would be a society without culture; but then he realized at once that it would also not be a society.

Then when does influence become plagiarism or copyright violation?

We have spent many years working out the answer to that question for human artists (or writers, or musicians, or other workers in the fields our twenty-first century calls “creative”). The answer is that influence becomes theft when the artist adopts all or part of another’s work without credit or permission. It is not plagiarism if the original is credited, but it may be copyright violation if a large part of the work is adopted without license. For example, you might print a new edition of The Satanic Verses and credit Salman Rushdie as the author; that would not be plagiarism, but it would be copyright violation if you did not have the permission of the copyright holder. On the other hand, you might publish a novel that is word-for-word identical to Can You Forgive Her? by Anthony Trollope and claim it as your own; that would not be copyright violation, but it would be plagiarism, even if the only penalties would be social and not legal.

There is a certain latitude for “fair use” in quoting from or alluding to another’s work, and since it is impossible to draw a sharp line around the area of fair use, intellectual-property attorneys will never starve. In many jurisdictions (not including the United States), the question of “moral rights” makes the attorneys even fatter.

Now, how do the answers we have worked out for human “creatives” apply to the creations of artificial intelligence?

It seems to Dr. Boli that we can think of the bots in two different ways. Either they are minds in their own right, producing their own art the way an artist working for hire would do; or they are mindless tools in the hands of their users, like a more sophisticated (though not more artistic) version of a camera or a paintbrush.

Which of those two ways we choose is probably irrelevant, since in either case Dr. Boli’s conclusion would be the same. We can judge whether theft has occurred only by looking at the “art” the bots produce. If, after studying the works of all the artists in the world, they produce works in which substantial parts of the art they have studied are reproduced without permission, then those parts are stolen; and if they are under copyright, there are legal penalties to be paid. But if the bots’ productions are merely in the style of the artists they have studied, then they are no more plagiarizing than a human artist who paints Indianapolis street scenes in an Impressionist style is plagiarizing Monet or Pissarro.

This seems to be the case with visual art by artificial intelligence: it does seem to take what it learned and transform it (a term that is very important in American copyright law) into something original. It may not be good, but it is original, which is the moral or legal question to be answered.

It would be lovely to think that the corporate keepers of the bots trained them carefully to stay on the right side of that legal line. But if they are on the right side, it is almost certainly pure accident. As a counterexample, many open-source programmers complain that the AI bots that spew out code often take whole long sections from published open-source programs without crediting the original authors or abiding by the other terms of the open-source licenses. That is plainly illegal, but Microsoft, for example, publishes “agreements” in which you agree, merely by existing, not to prosecute the company for those violations, so we suppose it is quite all right and everyone ought to be happy.

In the case of art and literature, though, American courts seem to have settled on what Dr. Boli thinks is the most reasonable interpretation of the law. In the class-action suit against Anthropic, the court decided that it is fair use to train the bot on electronic copies of books, just as it would be fair for you to read those books and learn from them—if you have the right to use those books. But it is not legal to download a bunch of pirated copies and keep them for training purposes, any more than it would be legal for you to do the same thing.

In other words, if the bot is a tool, then the humans who use it are allowed to use it as a tool for learning skills and styles in order to make original works—but not for reproducing the copyrighted works of others. If the bot is an intelligence in its own right, then it is a sort of pet or minor person, and its keepers or guardians are responsible for making sure that it stays within the rules of fair use.

To Dr. Boli this seems like the only possible answer to the question of the legality of AI art. It does not begin to answer the question of the desirability of AI art. For that, Dr. Boli sticks to the answer he gave before: he thinks that, eventually, there will be art, and possibly even good art, that has used AI as part of the process. But most AI art—like most art in general—will be slop.