Posts filed under “General Knowledge”

Advertisement.

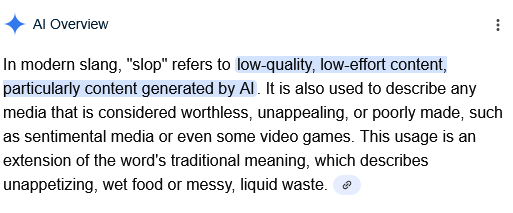

WHAT IS SLOP?

Γνῶθι σεαυτόν, as the graffiti said on the Temple of Apollo at Delphi. This is, as the young people say, very meta.

The screenshot extract from Google results is quoted for the purpose of mockery, which is one of the purposes that qualify as “fair use” in American legal theory.

ASK DR. BOLI.

Dear Dr. Boli: What is the difference between religion and superstition? —Sincerely, Just Sitting Here in Peter’s Chair Wondering.

Dear Sir or Madam: The distinction between religion and superstition is the distinction between the grammatical first and second persons. Religion is what I believe about the supernatural. Superstition is what you believe about the supernatural.

ASK DR. BOLI.

Dear Dr. Boli: Why do laws exist? —Sincerely, Samantha in Mr. McRoberts’ Fifth-Period Civics Class, and if you could get me an answer before the bell rings that would really help.

Dear Miss: You will hear two completely incompatible theories about why laws exist. The idealists will say that laws exist to protect the poor and humble from the depredations of the powerful. The cynics will say that laws exist to maintain the ascendancy of the powerful over the poor and humble.

However, the real answer is much more pragmatic. Laws exist to give legislators something to do, thus keeping them off the streets. If you have ever met an average state legislator, you know that this is a necessary and laudable goal.

EMANCIPATION FROM TERMS AND CONDITIONS.

Now, obviously, if you have lost control of the most intimate and closely guarded aspects of your life to a corporation, you are the slave of that corporation. And here is where you might expect Dr. Boli to wax eloquent, or at least sarcastic, on the evil intentions of big corporations. But that is not going to happen. It is certainly true that some corporations have evil intentions. Corporations are people, too (says the Supreme Court); and some people are good and some less resistant to temptation. But terms and conditions are not imposed on us primarily because corporations are evil. They are imposed because corporations are afraid.

What are they afraid of? Aside from big hairy spiders, of course?

Their fears are very reasonable. They worry constantly that they will be held liable for millions of dollars in damages because of some ordinary and necessary aspect of their business.

For example, you set up a photo-sharing site where people can upload pictures and share them with their friends. How delightful! Now someone is suing you for copyright infringement because you have his copyrighted pictures stored on your server—even though he uploaded them to your server himself. “Did you have written permission to store those copyrighted pictures?” attorney for the plaintiff asks in court. Well, no, not really.

You should have had some terms and conditions. And you should have had them written by a lawyer, who would have the expertise to think of all the unlikely but possible ways other lawyers might try to exploit the courts against you.

So the other companies in your business, having watched your downfall with alarm, do just that. And so do you, if you have the good luck to emerge from bankruptcy and try again. And the more your lawyers think—or, in other words, the better they are at their job—the more the terms and conditions pile up into tens of thousands of words. Now, a site like yours needs at least thousands if not millions of users in order to make a profit; you simply cannot negotiate an agreement with each one of them individually. And you quickly discover that most prospective users will just go somewhere else if you make them e-sign a bunch of documents before they can interact with your site. So you make the terms and conditions apply to everyone who uses the site, just by using the site—and the courts, realizing that modern business would be impossible without these “agreements,” go along with it.

Make a few assumptions, draw the obvious conclusions, and modern slavery is the inevitable result. It is quite impossible for you to know the terms of all the “agreements” you have accepted, but it is just as impossible for businesses to offer you their services without those terms and conditions.

Are we trapped, then? No! Dr. Boli has a pair of sharp shears (labeled

The proposal begins with an observation: every business in each category has the same legal problems to face. Your business may have a few unique aspects, but the great majority of your legal fears are the same as the legal fears of all the other players in your field.

Why, then, should you not all use the same terms and conditions?

Right now, if you run a photo-sharing site, you have your own set of terms and conditions, and your own privacy policy, and so on. The competition has a different set of terms and conditions, but they address the same problems. That is, at the very least, inefficient; and from the point of view of the user, it is impossible. No one can read a separate set of legal conditions for every site on the Web.

Open-source software programmers have dealt with this problem in a very reasonable way. Instead of making a new set of terms and conditions for every bit of software they release, they pick one of a handful of well-known licenses. If you install software licensed under the MIT license, you can say, “Oh, I’ve seen this a dozen times before,” and you know what you’re getting into.

What we need is a similar way to consolidate everyone’s terms and conditions. It is impossible to read separate terms and conditions for every car you ride in, every app you download, every Web site you visit, every appliance you buy, every wi-fi hotspot you connect to. But it would be reasonable to read a short document called “Universal Wi-Fi Hotspot Terms” once, and then know that, whenever you saw the UWFHT logo, you could confidently agree to the terms you had already read and understood.

It is the multiplication of separate agreements that enslaves us, not the idea of agreements. Make the agreements few and easy to understand, and balance will be restored to the relationship between businesses and customers. Customers would be well-informed enough to point out the conditions they didn’t like. Corporations would have an incentive to adjust their terms and conditions so that consumers had a good impression of them. The “agreements” would become agreements, without ironical quotation marks.

How would we accomplish that? Government regulation might work. Better would be a network of trade associations pooling their resources to come up with the most equitable terms and conditions to apply in each industry. Then, of course, businesses that adopted these new universal agreements would have a strong advertising advantage. Buy from the business you trust—the one that’s up front with you—the one whose terms you know in advance—and not from that shady charlatan who hides who knows what wicked chicanery in his nonstandard terms and conditions!

The hardest part of the endeavor would be to get the lawyers on our side, because we seem to be taking food out of their mouths. But when the mob of attorneys with pitchforks shows up at our door, perhaps we can persuade them that there is a pile of money to be made in suing the corporations that persist in holding customers to nonstandard terms and conditions. As the standard agreements become more usual and expected and are adjusted with experience, they will become more immune to legal assault—but the one-off nonstandard agreements will begin to show their tattered edges and moth holes. Lawyers who can take advantage of those weaknesses will be doing the world a favor, and they may get rich in the bargain.

YOU ARE A SLAVE. NOW WHAT?

We have mentioned before that nearly everything you do comes with terms and conditions attached—an “agreement” that you agreed to without reading it, because it may well have been twenty thousand words long. You may have made multiple such “agreements” just today. If you have been alive for the past ten years, it is almost inevitable that you have “agreed” to more than a thousand of these articles of enslavement, and that is a very low estimate. And you are bound by these agreements that are not agreements.

If Party A can impose conditions at will upon Party B, then Party B is the slave of Party A. We must call things by their names, and only then can we begin to understand them.

But perhaps it is not as bad as it seems to be. Perhaps there is a kind of safety built into the system: we accept the terms and conditions because there is an unspoken agreement that the terms and conditions will not be unreasonable. Or, even if they are indeed unreasonable as written, the most unreasonable provisions will never be enforced, because corporations know that people will not tolerate the enforcement of unreasonable conditions.

Perhaps not now. But the conditions have become much more unreasonable over just the past two or three decades, and we have tolerated it just fine. Did you agree to let your corporate masters monitor your sex life? If you drive or ride as a passenger in certain brands of automobile, yes, you did, just by getting in the car.

Once we have admitted the principle that we can have conditions imposed on us, we are owned. We have fallen into the abyss, and the fact that we are still falling and have not yet hit the bottom does not make it less of an abyss. The next time you are confronted with terms and conditions to agree to, read some of them. Not all of them, of course: that would be unreasonable. But read enough to get an impression of the general tenor of the document. You will probably find that the various provisions, as they pile up in heaps too high to wade through, are all reinforcements of the same overall principle: you owe us everything and we owe you nothing.

It will be better in the long run, then, if we just admit that we have been enslaved.

And then what?

Now, before the Internet explodes with outrage for the five hundredth time today, Dr. Boli will point out that our condition of slavery is not at all like African slavery of the days before the Civil War. We have it easy. We are the privileged household slaves, not the tortured, abused, and short-lived field slaves. We call our condition slavery not because we have bloody stripes on our backs, but because it is necessary to understand that we have been placed under a kind of control from which we have no legal escape. It is a kinder, gentler slavery, but it is slavery.

So, once we have made the observation that we are slaves, what can we do?

There are two possible ways of dealing with this kind of enslavement. One is to be rich. If you are rich enough to hire lawyers more devious than the enslaving corporations’ lawyers (who, after all, are likely to be copy-and-paste timeservers), then you can make it inconvenient enough for the enslavers to try to impose their most outrageous conditions that they ultimately will not hold you to them.

But if you are not rich and well-lawyered, then you must learn to think like a slave.

That does not mean what you probably think it does. It does not mean that you must resign yourself to your condition and become a humble and obedient automaton, serving the master’s every whim. That may be what you think a slave is like, but that is because you have not known many acknowledged slaves. Through most of human history, slavery has been part of the fallen and broken human condition. And for most of human history, the reaction of the slave to the condition of slavery has been deviousness.

To learn to think like a slave, you must study Roman comedy. Plautus and Terence will show you how it is done. The slave must be one step ahead of the master at all times, to the point of making the master wonder whether it is worth the trouble to own slaves in the first place.

Once you have mastered the Roman comedies, you are ready for the advanced class. Here you study the works of Frederick Douglass, and learn how a modern genius deals with being a slave, with the ultimate goal not only of profiting in the short term but also of gaining permanent freedom. If you have not given yourself the pleasure of reading Douglass himself, Dr. Boli would certainly recommend his autobiographies—especially the first one, written in the heat of the fight for abolition. Mr. Douglass writes with anger, as you might expect, but also with a scalpel-sharp sense of humor. Slavery is an absurd condition, and no one is more absurd than the slaveholder who thinks he has a right of property in his slaves.

So we learn from Pseudolus and Frederick Douglass. We treat our masters with contempt—but devious contempt. If nothing belongs to us by legal right, then we will make everything belong to us by cleverness. Mr. Douglass will even teach us the art of combining deviousness with dignity. We can make the slaveholders wonder why they seem to have everything according to the law and yet never actually get anything they want.

There may come a time when the people rise up against their masters and defeat them on the only ground that will make any difference—in court. There may come a time when lawyers prove to the satisfaction of the highest court in the land that so-called agreements that, because they are so long and come in such numbers, are literally impossible for consumers to read are no more valid than a supposed contract that required one of the parties to levitate or teleport. But, until that distant day, we can learn to think like slaves and, like old Pseudolus, make pretty good lives for ourselves.

FROM THE ILLUSTRATED EDITION.

LIMITATION OF LIABILITY.

In no event will the Operator be liable to any person for any indirect, incidental, special, punitive, cover or consequential damages (including, without limitation, damages for lost profits, revenue, sales, goodwill, use of content, impact on business, business interruption, loss of anticipated savings, loss of business opportunity) however caused, under any theory of liability, including, without limitation, contract, tort, warranty, breach of statutory duty, negligence or otherwise, even if the liable party has been advised as to the possibility of such damages or could have foreseen such damages.

Now, remember that Dr. Boli’s doctorate of laws was conferred honoris causa, and furthermore not by Americans, so he does not understand American law, and is willing to be instructed by the lawyers among his readers.

The obvious meaning of the clause is this: No matter how careless I am, and even if you told me I was being careless and would probably hurt you, I am not liable for any damages I cause to you, under any legal theory known to man.

The agreement is one to which you agree simply by using the service: “By accessing and using the Website and Services you agree to be bound by this Agreement.” Many of these “agreements” run over twenty thousand words. By using the service, you have agreed that you have read the agreement, but you did not.

It seems to Dr. Boli that there are three possibilities here:

1. This “limitation of liability” is valid, and therefore all the personal-injury attorneys and other liability lawyers in the world will do you no good against anyone who has copied and pasted this clause into a user agreement to which you agreed simply by existing; and soon there will be no damages awarded to anyone, and all those contingency-fee attorneys who advertise on billboards will starve.

2. This “limitation of liability” will not stand up in court if in fact the liable party knew or should have known that the conduct in question was likely to cause damage, and the lawyer who put those words in there and told his client “this will protect you” was lying.

3. An American lawyer is something between a faith healer and a witch doctor, someone who tries to convince himself that his rituals and incantations are doing some good, even though his senses perceive only a puff of blue smoke and a foul odor.

These are the three possibilities that occur to Dr. Boli when he reads a “limitation of liability” like this one. But Dr. Boli would be interested in hearing from an American lawyer who can explain the current state of the law.

PINK.

Why is the world so pink?

Dr. Boli will tell you. It is because the American people are suckers.

These corporations are spending quite a bit of money on pinkening the environment so that we will see that they care about breast cancer. That money could, of course, be spent on research to cure breast cancer. But instead it is spent on pink. Our corporate masters want us to think well of them, because it makes us easier to manage; and they have discovered that turning on the pink lights, which everybody can see, is more effective at making us think well of them than donating an equivalent amount of money to medical research, which is not as visible no matter how many press conferences they call. We are suckers. We believe in the goodness of the corporation if it puts out a sign that says “We are good.” So corporations fund the lighting contractors, and the medical researchers starve.

MEMORANDUM.

To: All Employees

From: The President

Re: Ergonomics

All of us here at the Schenectady Small Arms & Biscuit Co., Inc., want to promote a productive work environment. I know that because I read it in a magazine in the dentist’s waiting room. My dentist has like a whole library in there, so every six months I get to catch up on my reading. So he had this magazine called Limited, the Magazine for the Smart Executive, and I thought, Hey, that’s me! And when I opened it up, the first article I came to was about this great new trend in work environments that makes them more productive, which it said is what everybody wants. A work environment is a place where people work. So like a job, but more environmental. This trend is called “ergonomics,” which looks like a big word, but it’s easy when you realize that it’s just made from two simple Greek words: ergo, which means “therefore,” and nomics, which means “stuff you eat.” I have no idea why it’s called “ergonomics,” because most of it isn’t about eating. But you should know about it, because it’s all about making the work environment better, and that’s what we all want.

I was only halfway through the article when the dental technician came to get me, but I got the gist of it. It’s basically about synergy, which is one of my favorite things. Last year for Boss’s Day my administrative assistant gave me a whole box of synergy. It looks like an empty box, but if you’re a smart executive you can see the synergy in it. Isn’t Mary Beth the best?

Anyway, the way ergonomics works is that you match the environment to the human beings who work in it. The article explained that people work better when the furniture around them matches the way their bodies are put together. It’s simple, really. Like, if you have to sit in a chair, that chair should have a shape that fits your body. And if you have to sit at a desk, then the things on the desk should be in the right positions for your arms to reach. The place you work and the shape of your body should fit together.

So when I got back to the office, I had Mary Beth do some numbers on that thing with the rectangles that she calls Extra Large (actually, she usually abbreviates it “XL”), and it turns out that it would cost a lot of money to make all our furniture fit our employees’ bodies. I mean, do you have any idea how many chairs there are just in the main building? So I said, “That’s a lot of money,” and she said, “Yeah, I suppose you’d think it was cheaper just to bend the employees around the furniture.”

See? This is why I say Mary Beth’s the best. I had her run the numbers (I don’t know why she kept saying “Please tell me you’re kidding” over and over again while she was doing it), and it turns out that her idea is surprisingly affordable, especially since my nephew Clyde is a chiropractor and he works cheap. So the immediate intent of this memo is to inform everyone to check your calendar to see when you’re scheduled for your upcoming appointment with Clyde. Together we can build the productive work environment that magazine says we all want.

With warmest regards,

J. Rutherford Pinckney,

President